Each copy of the human genome consists of about 3,200,000,000 base pairs, and includes about 500,000 repeats of the

LINE-1 transposable element (a

LINE) and twice as many copies of

Alu (a

SINE), as compared to around 20,000 protein-coding genes.

Whereas protein-coding regions represent about 1.5% of the genome, about half is made up

LINE-1,

Alu, and other transposable element sequences. These begin as parasites, and some continue to behave as detrimental mutagens implicated in disease. However, most of those in the human genome are no longer mobile, and it is possible that many of these persist as commensal freeloaders.

Finally, it has long

been expected that a significant subset of non-coding elements would be co-opted by the host and take on functional roles at the organism level, and there is increasing evidence to support this.

A notable fraction of the non-genic portion of human DNA is undoubtedly involved in regulation, chromosomal function, and other important processes, but based on what we know about non-coding DNA sequences, it remains a reasonable

default assumption -- though one that should continue to be tested empirically -- that much or perhaps most of it is not functional at the organism level.

This does not mean that a search for the functional segments is futile or irrelevant -- far from it, as many non-genic regions are critical for normal genomic operation and some have played an important role in many evolutionary transitions. It simply means that one must not extrapolate without warrant from discoveries involving a small fraction of sequences to the genome as a whole.

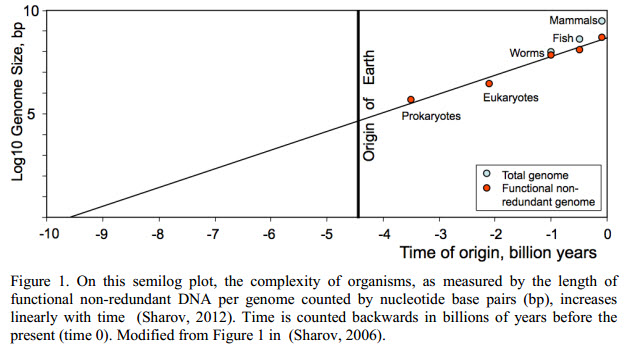

Moore’s Law, The Origin Of Life, And Dropping Turkeys Off A Building

Moore’s Law, The Origin Of Life, And Dropping Turkeys Off A Building Genome Reduction In Bladderworts Vs. Leg Loss In Snakes

Genome Reduction In Bladderworts Vs. Leg Loss In Snakes Another Just-So Story, This Time About Fists

Another Just-So Story, This Time About Fists