When we think of the genetic changes that had to take place during our evolutionary history, we typically think of changes that resulted in a gain of function, like genetic changes that resulted in a larger and more sophisticated brain, improved teeth for our changing prehistoric diet, better bone anatomy for bipedalism, better throat anatomy for speech, and so on.

In many cases however, we have lost genes in our evolutionary history, and some of those losses have been beneficial.

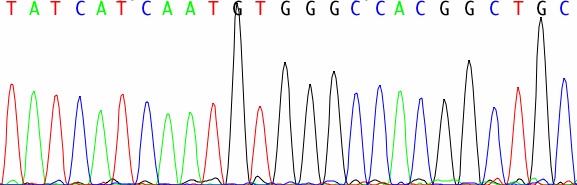

The most widely known example, found in every introductory biochemistry textbook, is the sickle-cell mutation in hemoglobin - a clear example of a mutation that damages a functional protein yet confers a beneficial effect. People with mutations in both copies of this particular gene are terribly sick, but those who have one good and one bad copy are more resistant to malaria. Another example is the

CCR5 gene - people with mutations that damage this gene are more resistant to HIV. In the more distant past, a universal human mutation in a particular muscle gene that results in weaker jaw muscles may have played a role in brain evolution, by removing a constraint on skull dimensions.

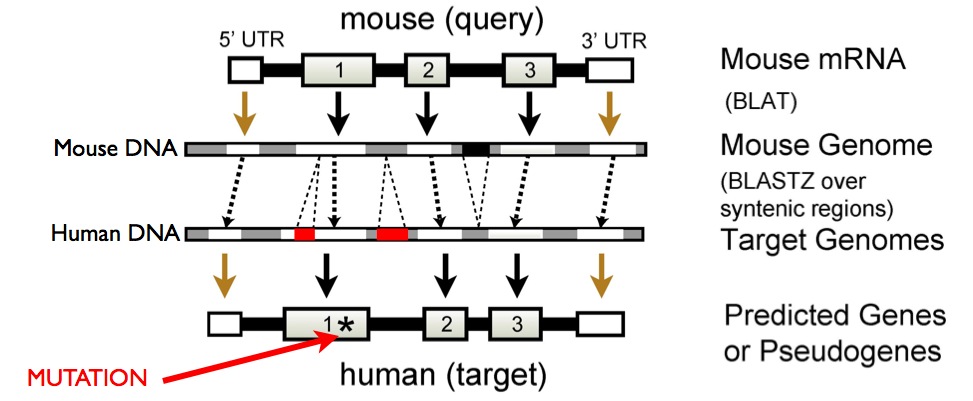

These few examples were found primarily by luck, but now with the availability of multiple mammalian genome sequences, researchers can systematically search for human genes that show signs of being adaptively lost at some point in our history. David Haussler's group at UC Santa Cruz, in a

recent paper, looked for the genes we lost as we developed into our modern-day human species. What they found could help us better understand our evolutionary history, and possibly the human diseases that are the side-effects of that history.

Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth

Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising?

Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising? Yep, This Should Get You Fired

Yep, This Should Get You Fired No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes

No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes