What Next For Messenger RNA (mRNA)? Maybe Inhalable Vaccines

What Next For Messenger RNA (mRNA)? Maybe Inhalable VaccinesNo one likes getting a needle but most want a vaccine. A new paper shows progress for messenger...

Toward A Single Dose Smallpox And Mpox Vaccine With No Side Effects

Toward A Single Dose Smallpox And Mpox Vaccine With No Side EffectsAttorney Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and his US followers over the last 25 years have staunchly opposed...

ChatGPT Is Cheaper In Medicine And Does Better Diagnoses Even Than Doctors Using ChatGPT

ChatGPT Is Cheaper In Medicine And Does Better Diagnoses Even Than Doctors Using ChatGPTGeneral medicine, routine visits and such, have gradually gone from M.D.s to including Osteopaths...

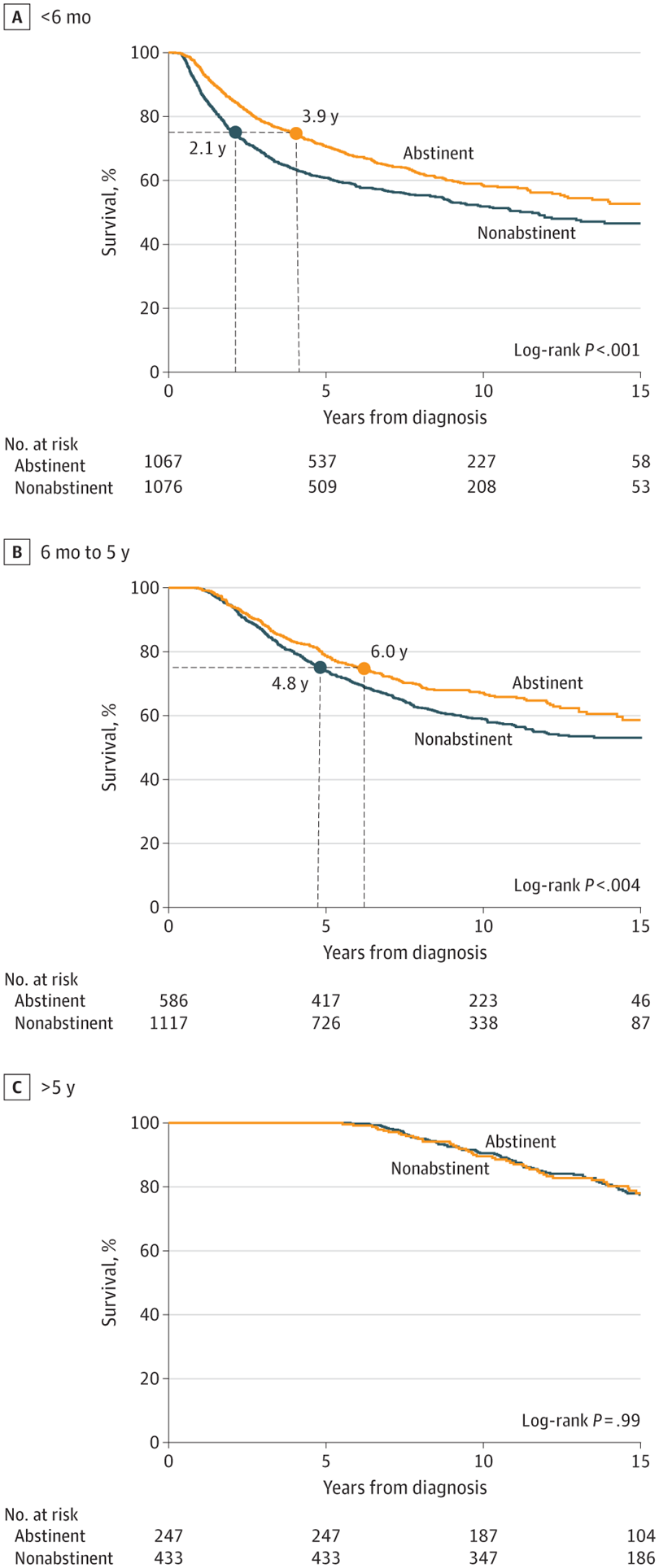

Even After Getting Cancer, Quitting Cigarettes Leads To Greater Longevity

Even After Getting Cancer, Quitting Cigarettes Leads To Greater LongevityCigarettes are the top lifestyle risk factor for getting cancer, though alcohol and obesity have...