Duckweed Science May Lead To Food That Farms Itself

Duckweed Science May Lead To Food That Farms ItselfDuckweed split into different species 59 million years ago, when the climate was more extreme than...

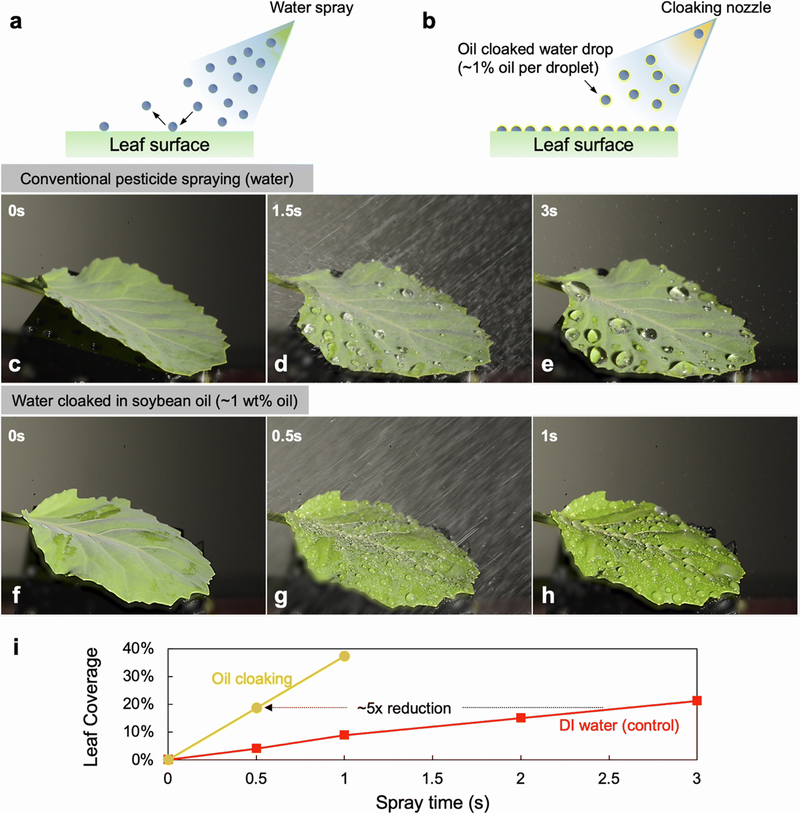

Sticky Pesticides Reduce Chemicals Needed To Protect Plants

Sticky Pesticides Reduce Chemicals Needed To Protect PlantsIt's easy for Greenpeace employees in cities to talk about farming but in the real world, without...

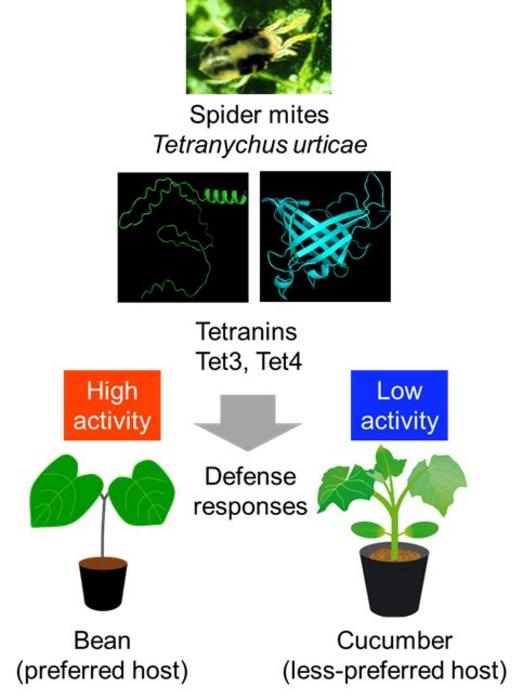

Genetic Engineering Could Solve Spider Mite Infestations With Fewer Pesticides

Genetic Engineering Could Solve Spider Mite Infestations With Fewer PesticidesThe world is producing more food using fewer pesticides than ever, thanks to modern science. The...

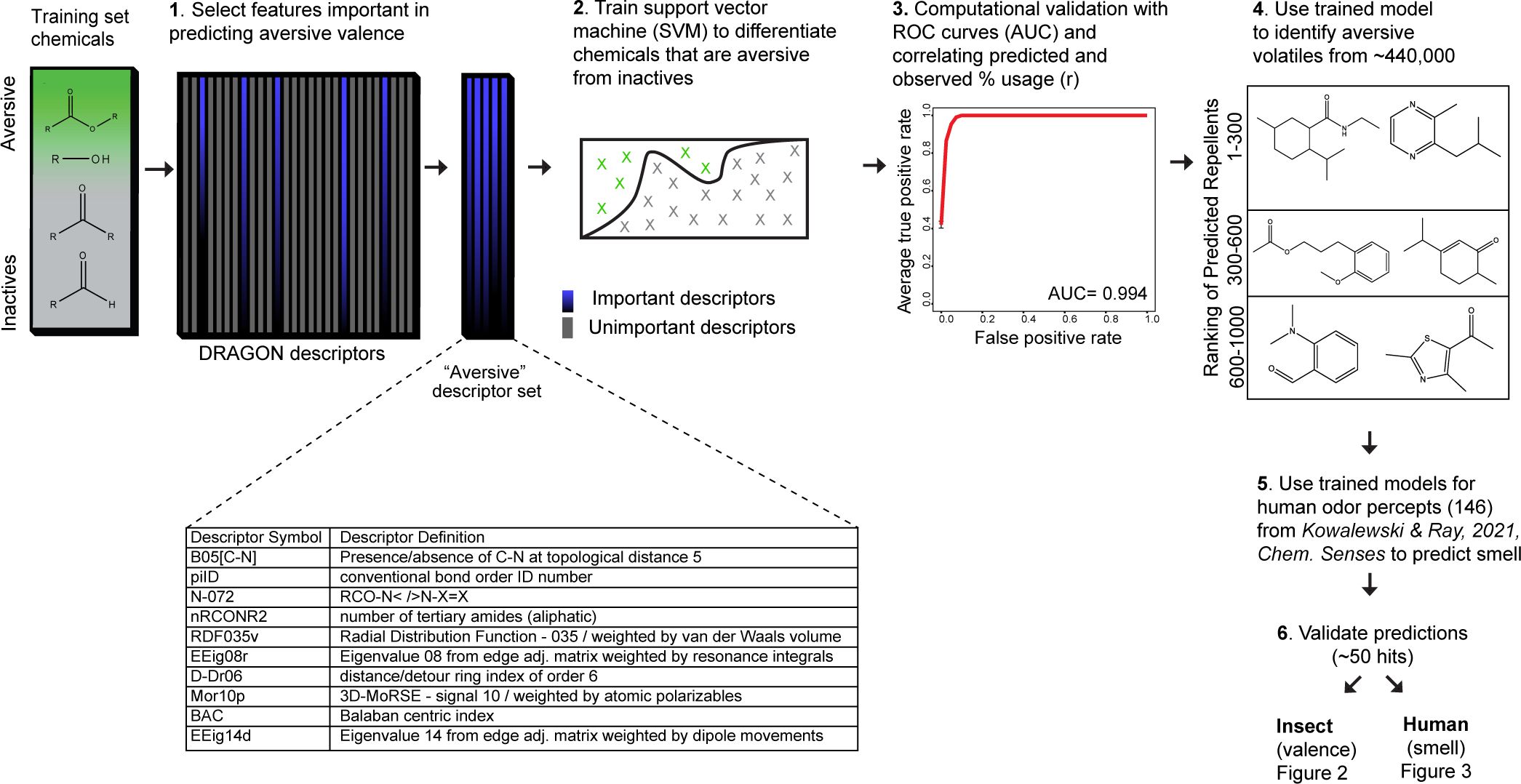

Cheminformatics: NIH Funds A More Scientific Mosquito Repellent

Cheminformatics: NIH Funds A More Scientific Mosquito RepellentToday, the best way to prevent malaria remains DDT. Though banned in the US by a politician over...