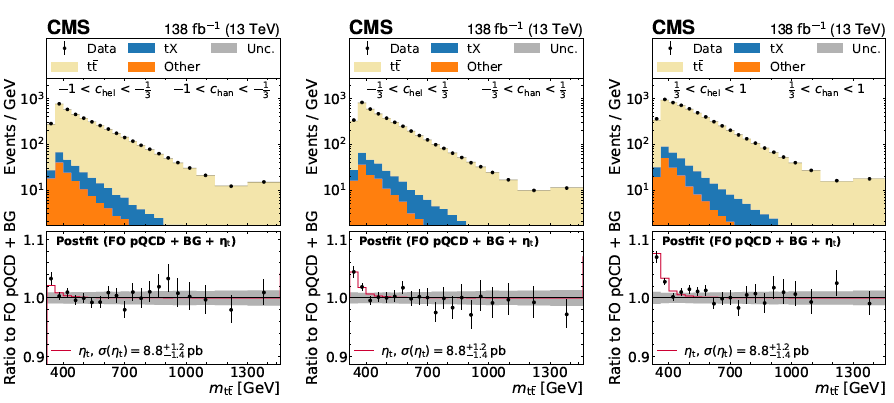

Toponium Found By CMS!

Toponium Found By CMS!The highest-mass subnuclear particle ever observed used to the the top quark. Measured for the...

The Problem With Peer Review

The Problem With Peer ReviewIn a world where misinformation, voluntary or accidental, reigns supreme; in a world where lies...

Interna

InternaIn the past few years my activities on this site - but I would say more in general, as the same...

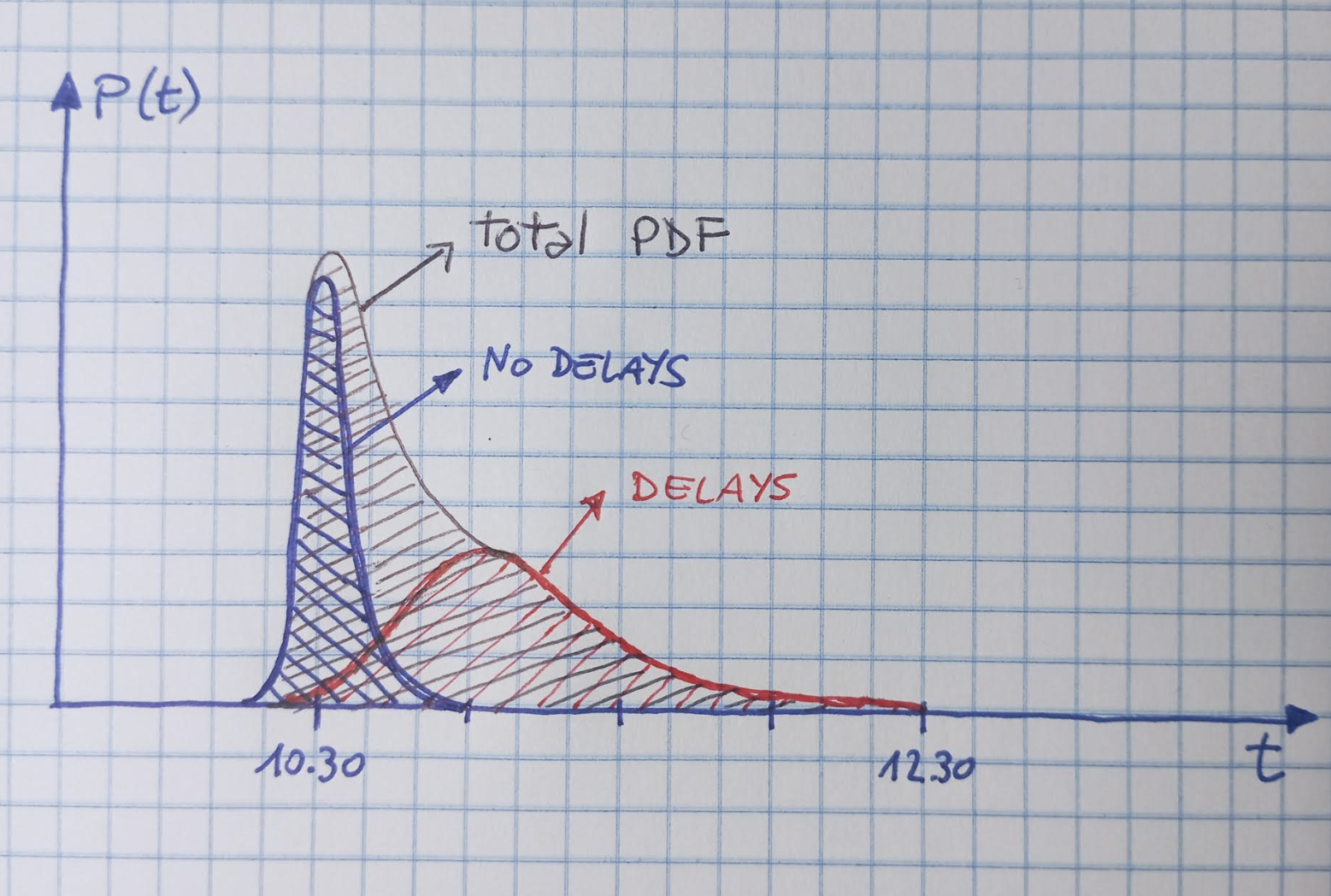

The Probability Density Function: A Known Unknown

The Probability Density Function: A Known UnknownPerhaps the most important thing to get right from the start, in most statistical problems, is...