In Genus Homo, the scientist is clearly the hero. True to the pulp tradition, the men are men and the dames are dames, but the scientist is the man among men. A group of passengers on a bus wakes up after an accident inside of a tunnel. They were traveling through rural Pennsylvania in late 1939, but they soon realize they’re not in Pennsylvania anymore. More precisely, where they crashed is no longer Pennsylvania, which ceased to exist as a political entity about one million years ago.

In Genus Homo, the scientist is clearly the hero. True to the pulp tradition, the men are men and the dames are dames, but the scientist is the man among men. A group of passengers on a bus wakes up after an accident inside of a tunnel. They were traveling through rural Pennsylvania in late 1939, but they soon realize they’re not in Pennsylvania anymore. More precisely, where they crashed is no longer Pennsylvania, which ceased to exist as a political entity about one million years ago.It turns out that the bus was passing through a tunnel when a catastrophic earthquake struck. The ensuing crash caused the release of an experimental hibernation gas, carried by a scientist on board; the gas caused everyone’s metabolism to drop to almost nothing. After a million years of hibernation the group wakes up to an unfamiliar world of giant birds and rodents, and highly intelligent apes.

Fortunately for the passengers, the bus was carrying a group of scientists headed for the annual AAAS meeting in Columbus, Ohio. The inventor of the hibernation gas died in the crash, but four others survived: a biochemist, a mammologist, and archeologist, and an ichthyologist. The brilliant, rational, hard-headed biochemist takes the lead, and the group, thanks to some shrewd scientific thinking, has soon managed to orient themselves in their new environment. (This doesn’t happen without some casualties - the faint-hearted ichthyologist, who clearly had it coming, gets eaten by giant birds.)

The dominant species of this future world are gorillas who have evolved speech and scientific thinking. The humans are captured, taken to a gorilla city, and placed naked (of course) in the gorilla zoo. (By the time the humans get their clothes back, two of the women are pregnant.) What follows is a classic story of role reversal - the humans are studied by gorilla scientists, who are trying to determine just how intelligent these gangly, hairless apes are. Thanks to Henly Bridger, the intrepid biochemist, the humans and gorillas learn to communicate, and the gorillas welcome their weaker evolutionary cousins into their society.

The dominant species of this future world are gorillas who have evolved speech and scientific thinking. The humans are captured, taken to a gorilla city, and placed naked (of course) in the gorilla zoo. (By the time the humans get their clothes back, two of the women are pregnant.) What follows is a classic story of role reversal - the humans are studied by gorilla scientists, who are trying to determine just how intelligent these gangly, hairless apes are. Thanks to Henly Bridger, the intrepid biochemist, the humans and gorillas learn to communicate, and the gorillas welcome their weaker evolutionary cousins into their society.Gorillas are just as scientific as their human precursors, and in fact even their government is organized according to highly scientific political principles. As a result, the gorilla society is stable, in contrast to their war-loving enemies, the baboons, who have come up with the completely insane governmental system of hereditary monarchy.

In fact a scientific political system is where the gorillas have succeeded - and humans clearly failed. Bridger, recalling developments in 1939 before the accident, speculates that humans did themselves in:

“Had it been that something - atomic energy - unleashed and in the hands of uncontrollable men, which brought mankind smashing down in self-destruction and gave the world to these apes?”

(It would be amazing - although not unprecedented - if this sentence about the possibility of nuclear destruction was written in the 1941 magazine version of the story, but I’m guessing it was a 1950 addition.)

Science in the hands of unscientific men - that was humanity’s downfall, and one which the gorillas have worked to avoid.

Unfortunately, while the gorillas have devoted themselves to a scientific society, the baboons have been preparing for an invasion. They drove the gorillas out of Africa, and are now prepared to pursue them in North America. de Camp and Miller do some very impressive baboon versus gorilla fight scenes, and the gorillas give the baboons a serious thrashing, aided by some human ingenuity and a neighboring society of reclusive but intelligent beavers,

Unfortunately, while the gorillas have devoted themselves to a scientific society, the baboons have been preparing for an invasion. They drove the gorillas out of Africa, and are now prepared to pursue them in North America. de Camp and Miller do some very impressive baboon versus gorilla fight scenes, and the gorillas give the baboons a serious thrashing, aided by some human ingenuity and a neighboring society of reclusive but intelligent beavers, Underlying Genus Homo is the notion, common in 1940's and 50's pulp sci-fi, that we fail when we’re not scientific enough. We can solve our problems through rational thinking. While John McClane can certainly get you out of a jam, so can Dr. Nick Tatopoulos. What’s more, scientific thinking is not only about controlling nature; it’s about self-control. de Camp and Miller pay homage to Enlightenment ideals with a story of rational thinking victorious over uncontrolled passion.

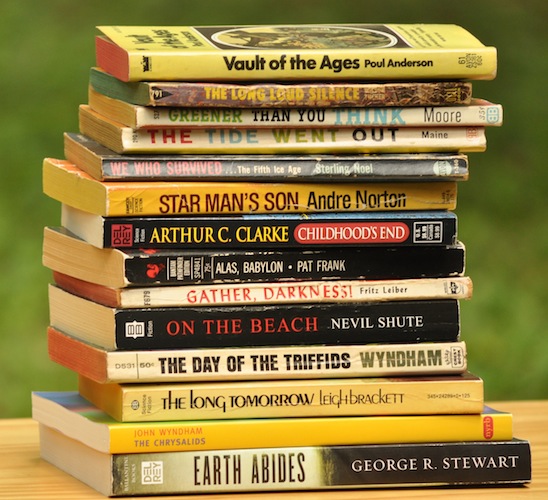

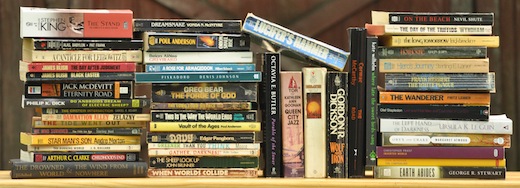

Next up in our post-apocalyptic survey: 1951, and a great British Golden Age novel: The Day of the Triffids.

Read the feed:

Comments