I say orgy: its a bacchanalian romp of differing misconceptions and twisted logic - basically, nothing out of the ordinary for a creationist, for whom apparently the addition of even more terrible ideas can only strengthen your argument. Very quickly, I got bored of the tedious process of writing a comment correcting these misconceptions, and I was just about to ignore it and start writing my next article.

That is, until circularreason, showing a surprising amount of humility, said

I would like to hear your thoughts on the fallacy of missing links, I am reasonable and willing to listen.Now, there is something that I am willing to bend on. You see, missing links, or rather, the apparent lack of them, are something that is bandied around irritatingly commonly on rant-threads like these. Their alleged absense is something that many creationists believe represent the nail in the coffin for evolution, and creationists act as if it is something that us paleontologists are all embarrassed about, fervently collecting in the desperate hope that one will turn up.

But, of course, this is absolute rubbish, and their insistence on using such arguments only does more to highlight their complete lack of any understanding of evolution, as I will outline here.

(I warn you, I lost an entire afternoon of work typing it, and it ended up being bit of a monster of an article!)

Snakes and ladders

Whilst nobody would claim to believe in such an idea these days, dating as it does from the time of the Greeks, most people in their mind's eye see some version of this story. Many understand macroevolution by envisaging a grand procession of life, where all creatures, through time, climb inexorably up this ladder, finishing with the the proud human, the most evolved of all beasts.

This is an unfortunate misunderstanding. I find myself speaking to a large amount of people who are genuinely surprised when I tell them that we didn't evolve from chimpanzees. They think I'm winding them up when I tell them that there's no such thing as the missing link between chimpanzees and humans, simply that we share a recent common ancestor with them. This common ancestor is likely to look similar to the two of us, but it need not be.

Evolution, then, is not a ladder. It's not even a tree. It is a thick, tangled bush, with no up and down. All we see today is the continuously growing ends on the twigs of this bush, which can split and slowly diverge. We can only have missing links if we have a chain, whereas what we really have is ends, with missing twigs. Hence no missing links.

Even the idea of a tree, with increasing complexity upwards, is wrong. Yes, many groups are characterised by increasing complexity, but many are characterised by an increasing loss of complexity. Some may lose an entire life stage. It's still progress, but not necessarily in the "upwards" direction. No living animal is more evolved than anything else, it may have simply evolved to retain its primitive characters.

But perhaps I am being pedantic - or semantic, anyhow. It is, of course, true that there are such things as transitional forms. By this, we mean that lineages can slowly accrue changes in their morphology through time. It is perhaps this concept that many refer to, rather than a chain of being as such. Maybe if people referred to transitional fossils it wouldn't irritate me so such.

Transitional fossils...?

A cladogram of dinosaur evolution.

We are not out of the woods yet, though. The likelyhood of finding a fossil that represents an ancestor of any sort of other organism, a member of one of those queues of organisms between known organisms on a cladogram, is astronomically low. The chance is even lower when we look very deep into the fossil record - so much so, that we have almost certainly never found one.

Surprising? It shouldn't be - think about it. Groups of organisms are continually evolving, groups migrating, changing, constantly splitting from one another in a fractal way. Are we really likely to accidentally stumble across one particular animal that is a member of a group that is a direct ancestor of another group we know about? No, of course not.

We have to image the lines on a cladogram as being a zoomed out line of our ancestors, a long queue stretching back towards our common ancestor with the next twig. Its along these lines that we slowly change. If the organism bears a resemblance to another or seems to be transitional, it could well be on a myriad of small offshoots from our line of ancestors, and could even be close to our line, but the chances of it actually being on our line is tiny. Walking through an old graveyard, are any of the gravestones likely to be an ancestor of yours? How about a skull in an African cave? Or a fossil monkey in a swamp? Even taking into account pedigree collapse, its still highly unlikely.

Transitional fossils do exist. Its just that they aren't necessarily the precise ancestors of organisms that we see; rather, are members of a cloud of organisms treading along some of the same evolutionary ideas, being as they are closely related to one another. Out of this maelstrom of different lineages there may be just one thread that gives rise to another important lineage. The fossils in this cloud still give us a chance to test our hypotheses about how the trends may have occurred in the lineages we're interested in. But they may not necessarily a true link in the chain.

That's the true art of paleontology, you see: using examples from the fossil record to infer trends and to test hypotheses about the nature of evolution. To assume that it is simply trying to make a sort of flip-book of evolution through time is incredibly ignorant.

Zeno's paradox

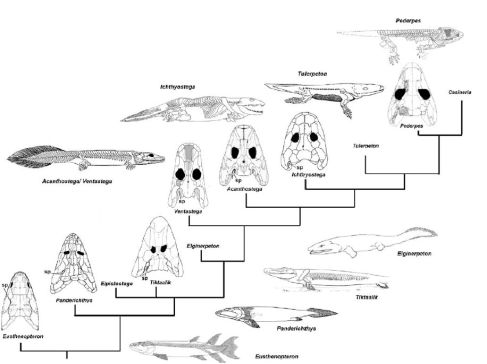

Tetrapod evoltuion: too many transitional fossils

A particularly egregious taunt often flaunted by creationists is "Give me just one missing link fossil and I will believe you". It's particularly loathsome because as soon as you present said creationist with a perfectly decent transitional fossil, they demand a link between those three fossils. And now there are two gaps to be filled with more missing links. Like the distance between Achilles and the tortoise in Zeno's paradox, this continues ad infintum.

How many fish to tetrapod intermediates do you want? Like it or not, the bigger problem that tends to be encountered more often in paleontology and related disciplines these days is that there are far too many plausible ancestors to place on our cladogram. The difficult bit is deciding which of these are closer to us and which are further away.

Mosiac evolution

Another related irksome point is the the very unitary approach taken to organisms. Whilst it is true that the unit of selection is at the organismal scale, the body parts that evolve may be at different rates. This concept is known as mosaic evolution, and is at the basis of modern cladistics (the possession of the most derived body parts, the synapomorphies, define the group as a whole).

Another related irksome point is the the very unitary approach taken to organisms. Whilst it is true that the unit of selection is at the organismal scale, the body parts that evolve may be at different rates. This concept is known as mosaic evolution, and is at the basis of modern cladistics (the possession of the most derived body parts, the synapomorphies, define the group as a whole).For example, in human evolution, bipedality evolved very quickly but large brain size evolved slowly and later on. So we will never find a fossil with both a mid-sized brain and an average adoption of bipedality; its just not how it happened. Similarly, we wouldn't necessarily expect the transitional form between maniraptors and birds to be something with medium length claws, medium length tail and legs and slightly asymmetric wing feathers. Archaeopteryx exemplifies this, with its mix of more bird like features, like a wishbone and asymmetric flight feathers, with more primitive characters, like a long tail and legs.

Macro to micro

Peter Sheldon's landmark study of welsh trilobites is a great example of gradual evolution in the fossil record

Many creationists these days seem to have quietly abandoned their objection to evolution at small scales. God knows why, but I presume its because the ark would sink with the sheer weight of beetles, molluscs and lice (every animal would of course have to be infested with every sort of parasite imaginable, of course). To do this, they seem to have invented a dichotomy between macroevolution and microevolution, envisaging them as different processes. They are both valid terms in evolutionary biology, but both at heart driven by the same inherent processes at viewed at different scales, and thus the dichotomy is false in this sense.

Where am I going with this? Well, all I mean to say is that; acceptance of microevolution is a wise thing, because there are cliffs worldwide stacked full with transitional fossils, if you accept evolution at the species level.

Rocks worldwide are dated relative to others by the gradual change of the constituent fossils that make them up. Unless you want to dispute the most basic tenet of geology, namely that the rocks on top are younger than those underneath, you cannot dispute that these organisms are slowly changing through time. Gradual evolutionary change has been noted in trilobites, bryozoans, bivalves, you name it. Its just that, because these organisms are marine, small and shelly, they have an exceptionally good fossil record.

If we had a similarly good record for, say birds and maniraporan dinosaurs, it would truly be a wonderful thing. But think how lucky we are to be able to say what we can about bird evolution. How fortuitous that those Archaeopteryxes should have died and fell in a stagnant lagoon? We may not have as good a resolution as we do for shelly marine critters, but we can still make out the general trend.

A god of the gaps

How about the many distinct gaps in the fossil record though? Is god quickly changing the organisms for more complex ones?Asides from the large gaps due to pauses in sedimentation, it is true that in many sedimentary columns, a group may appear, then disappear entirely and be replaced with something different, with little sign of transitional forms between them. Hesitantly then, I'll drag punctuated equilibrium theory into the fray, kicking and screaming because of all the times it gets misrepresented and misunderstood.

The way it works is that, at this scale, it is expected that any evolving will be done elsewhere. Natural selection generally acts to stabilise forms, trimming gaussians of character distribution at the edges like neat topiary bushes. So, a form may generally stay the same for a long period of time. If, however, a splinter group of random organisms gets separated and ends up elsewhere, they will gradually diverge from the rest. This is either because of different ecological niches being available, or simply through a lack of being able to recombine your genes with the rest of the group - a bit like the way that dutch-speaking people can no longer understand afrikaans, even though the two languages were once the same thing. And like when dutch people visit south africa on holiday, once the two are reintroduced they are no longer compatible. But, crucially, because the evolution of the splinter group occurred elsewhere, there is no record of it in the sedimentary column, and hence the transitional forms are elsewhere. And, given the incompleteness and geographical bias of the fossil record, they are likely to be unseen.

My worry about introducing Punc-Eq is because it is often thought about as some sort of ad-hoc, deus-ex-machina argument; a cover-up story. Let me say it clear: Punc-Eq is not some sort of excuse. Nor is it the rule. Punc-Eq has been conclusively proved by a study on bryozoans, as has gradualism; the two occupy a continuum, and the results of multitudinous studies done on it have formed a general theory of microevolution. There are, I'll admit, many gaps in our understanding of the way it works, but as with all science, that's the fun bit.

The point to draw from all this, if you haven't understood any of the above explanations, is that the need for transitional fossils, at all scales, is simply not there. They are of course, handy, illustrative of processes, and provide the most direct proof of our hypotheses, but they are by no means the only means of proof that two lineages are related.

Was there a point to me typing up this monster of an article?

Wouldn't it be great if a creationist read this and thought: "Hmmm. It appears I have been mistaken for all these years, and I think maybe it's time to join the world of logical thinking". Wouldn't it be great if just one person did that? Will circularreason change his mind?

Depressingly, I doubt it very much, and that's the very reason why I am generally reticent to answer creationists. But I'd like to think that, at least I can provide reassurance for anybody teetering on the edge, worried about whether the lack of transitional fossils is something that keeps paleontologists awake at night, and considering converting to the dark side.

So, to this person, then; re: the lack of missing links: Don't worry, we've got it covered.

Comments