By 2009, a paper even showed how easy it was to use a dead fish to make interpretations about emotion, and achieve the sought-after "statistical significance." Gone was the promise of clinical information that might help with depression, cognitive decline, and brain disorders, and the reason was humans.(1)

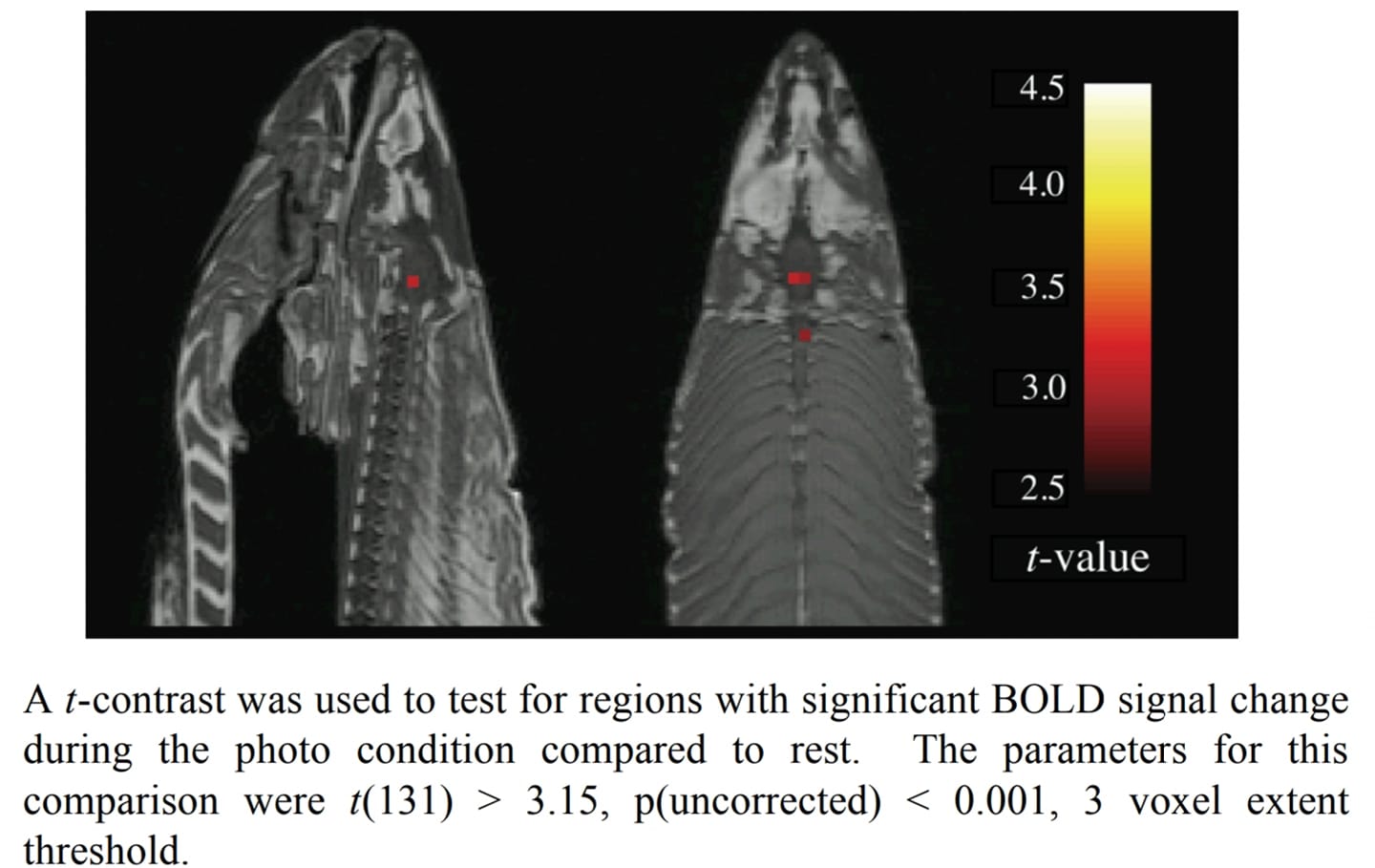

Like epidemiology, where data dredging or hypothesis after results are known may not be intentional, fMRI is subject to false positives in part because the data sets are huge. Using coin flips, you can show coins are prejudiced against heads with enough rows and columns. Or tails. And in fMRI if multiple comparisons correction is not utilized the results could be statistically significant, yet completely crazy.

Want to show Mindfulness is more effective than Scientology at clearing Thetans? Okay, that was an April Fools Day article here, but it was successful because it's not the craziest thing you'd see using fMRI.

A new editorial says machine learning algorithms (AI, if you must, but it's not) can improve results, as long as data sets are not too large. Weak associations can become stronger without false positives. It just requires apt use of pattern recognition. Right now, the field remains in its infancy because humans subjectively decide what is normal and what is different and how important it is, and fMRI was used to make all kinds of supernatural claims. That's fine for getting into the New York Times but has zero clinical relevance, because very little is done entirely in some small section of the brain.

If you want a pizza one time will the desire all be the same in an hour? Will it be the same for me? Those rushing to publish fMRI were arguing just that without acknowledging that fMRI can't tell you what an individual's brain activation will look like from one test to the next - but pattern recognition perhaps can.

If it holds up, the benefit is smaller datasets still creating better associations. It still faces a big hurdle. Very little will be causal any time soon, but to even be exploratory there has to be real knowledge of brain activity linked to specific ad hoc thoughts and experiences. We know humans have been terrible at interpreting what the input or output means so machine learning has to overcome that, even being tuned by humans. Which means the big obstacle is not machines or test subjects but "finding the right task to capture the state,” as Dartmouth Psychology Professor Tor Wager puts it.

NOTE:

(1) The study didn't start out to debunk fMRI but they followed protocol they would with humans to test their machine. They hooked the salmon up, asked it baseline questions, etc. and got a lot of data (no answers from the fish, obviously.) It was only later that they used the huge volume of data to learn how to do better fMRI and realized they had to do thousands of comparisons, which meant a whole lot of false positives - the multiple comparisons problem.

Comments