Nature carried a provocative article last week laying the ground work for what should be a fiery debate over the nascent field of genoeconomics. The prestigious American Economic Review is set to publish a peer reviewed paper co-authored by two economists, Quamrul Ashraf and Oded Galor, that argues that a country’s economic well being could be linked to the population’s genetic make-up. Earlier versions of the article  have been available on the web for a few years, and it’s aleady stirred quite a controversy.

have been available on the web for a few years, and it’s aleady stirred quite a controversy.

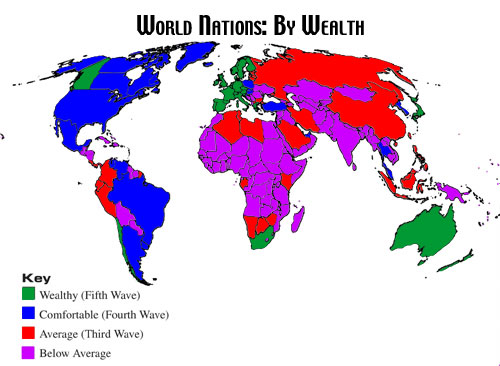

According to Nature: “The paper argues that there are strong links between estimates of genetic diversity for 145 countries and per-capita incomes, even after accounting for myriad factors such as economic-based migration. High genetic diversity in a country’s population is linked with greater innovation, the paper says, because diverse populations have a greater range of cognitive abilities and styles. By contrast, low genetic diversity tends to produce societies with greater interpersonal trust, because there are fewer differences between populations. Countries with intermediate levels of diversity, such as the United States, balance these factors and have the most productive economies as a result, the economists conclude.”

The term “genoeconomics” was coined only a few years ago. Spurred by groundbreaking public policy and social and economic research at the University of Chicago over the past two decades, economists have been expanding their wings, exploring the role of economic factors in our culture. The subject became mainstream after the bestselling success in 2005 of Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything by UC economist Steven Levitt and New York Times journalist Stephen Dubner. Within a few years, economists began turning their sights on the intersection of genetics and economics.

In May, the Boston Globe ran a fascinating piece, In Search of the Money Gene, featuring some of the young pioneers, Phillip Koellinger, now a professor at Erasmus college, then a MIT student but now a professor at New York University. Within a few years, a plethora of the best and the brightest in economics had jumped into the field—and the fray.

Their basic premise—which is incontestable in its most superficial form—is that genetics underlies many of the things, like risk-taking, patience and generosity that society has traditionally assumed are shaped totally by social and environmental factors. The challenge is to what degree scientists can tease out these genetic factors and what patterns might be found in various genetic groups, such as by sex or countries or ethnic and religious populations. Clearly, it’s potentially explosive stuff.

Their basic premise—which is incontestable in its most superficial form—is that genetics underlies many of the things, like risk-taking, patience and generosity that society has traditionally assumed are shaped totally by social and environmental factors. The challenge is to what degree scientists can tease out these genetic factors and what patterns might be found in various genetic groups, such as by sex or countries or ethnic and religious populations. Clearly, it’s potentially explosive stuff.

Leon Neyfakh in the Globe traces the movement—that’s what it has already become—to 1976, when the late University of Pennsylvania economist Paul Taubman published the results of a study in which he followed the financial lives of identical twins. The congruence in their “economic lives”—even in cases in which identical twins had been separated and raised in different cultural situations—was striking. Taubman estimated that between 18 percent and 41 percent of variation in income across individuals was heritable. Spurred by the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2000 and the budding of the field of neuroeconomics (the study of how economic decision-making functioned inside a person’s brain), the groundwork was laid for the emergence of genoeconomics.

It’s fascinating and controversial research. “I’m really worried that if [tracing behaviors to genes] should become possible, it may lead to a lot of things that we don’t want,” Neyfakh quotes Koellinger as saying. “I very firmly believe that information about your genetic makeup is probably the most private thing you could possibly have, and there should be extremely tight protections to make sure that no one gets their hands on this data unless you as an individual explicitly want this.”

No wonder that Ashraf and Galor’s paper is already prompting out-cries from the “we shouldn’t be discussing such things” crowd. The digital ink is not even dry and yet the authors are facing charges of genetic determinism and racism. Geneticist David Reich of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Harvard University paleoanthropologist Daniel Lieberman and more than a dozen other Harard professors have written an open letter highly critical of the paper and decrying its potential for mischief: “[T]he suggestion that an ideal level of genetic variation could foster economic growth and could even be engineered has the potential to be misused with frightening consequences to justify indefensible practices such as ethnic cleansing or genocide,” the letter said.

The reaction comes across as overheated. The paper had in fact been peer reviewed by economists and biologists and is not presented as definitive. Ashraf and Oder make a point of noting that they are merely using genetics as a proxy for other factors that can drive an economy, such as history and culture, so charges of determinism appear misplaced, serving mostly to raise the threat of soft censorship.

A taboo invariably emerges when the nexus of genetics and behavior are discussed. It was almost impossible to have a reasoned discussion about The Bell Curve or either of my two popular books on population genetics: Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It and Abraham’s Children: Race, Identity and the DNA of the Chosen People.

This is not an endorsement of this latest salvo in the ‘gene wars’ debate. It is a reminder that genetics is opening wide new doors of inquiry. It would be dangerous to close them based on concerns the previous inquiries into human differences have been misused. As we never know where new advances in science will originate we’re far better served by vigorous debate. Let’s hope more researchers pursue this subject and with even more intellectual rigor—and their work is welcomed as a appropriate subject for debate and discussion.

Check out the Genetic Literacy Project, which carried this article in this week's GLP Weekly Digest.

Jon Entine, founding director of the Genetic Literacy Project, is senior fellow at the Center for Health&Risk Communication at George Mason University, and a senior fellow at the Statistical Assessment Service (STATS).

Comments