A team of high school students analyzed data from the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) and discovered a never-before-seen pulsar which has the widest orbit of any around a neutron star - one among only a handful of double neutron star systems.

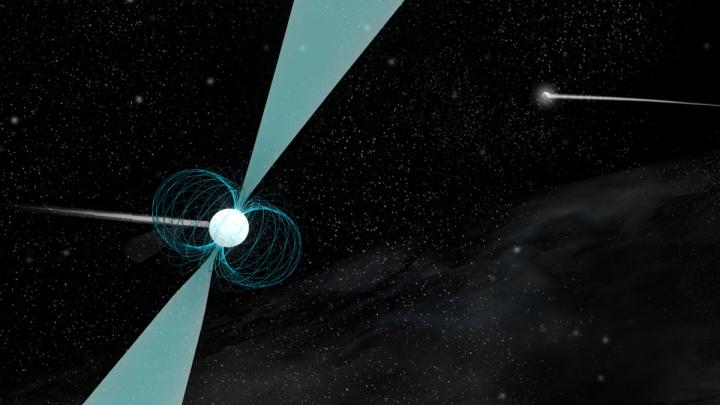

Pulsars are rapidly spinning neutron stars, the superdense remains of massive stars that have exploded as supernovas. As a pulsar spins, lighthouse-like beams of radio waves, streaming from the poles of its powerful magnetic field, sweep through space.

When one of these beams sweeps across the Earth, radio telescopes can capture the pulse of radio waves.

About 10 percent of known pulsars are in binary systems; the vast majority of these are found orbiting ancient white dwarf companion stars. Only a rare few orbit other neutron stars or main sequence stars like our Sun. The reason for this paucity of double neutron star systems, astronomers believe, is the process by which pulsars and all neutron stars form.

An artist's impression of pulsar PSR J1930-1852 shown in orbit around a companion neutron star. Credit: B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF)

When a massive star goes supernova at the end of its normal life, the explosion can be a little one-sided, imparting a "kick" to the remaining stellar core. When this happens, the resulting neutron star is sent hurtling through space. These kicks -- and the corresponding mass loss from a supernova explosion -- mean that the chances of two such stars remaining gravitationally locked in the same system are remarkably slim.

This pulsar, which received the official designation PSR J1930-1852, was discovered in 2012 by Cecilia McGough, who was a student at Strasburg High School in Virginia at the time, and De'Shang Ray, who was a student at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Baltimore, Maryland.

These students were participating in a summer Pulsar Search Collaboratory (PSC) workshop, which is an NSF-funded educational outreach program that involves interested high school students in analyzing pulsar survey data collected by the GBT. Students often spend weeks and months poring over data plots, searching for the unique signature that identifies a pulsar. Those who identify strong pulsar candidates are invited to Green Bank to work with astronomers to confirm their discovery.

Astronomers determined that this new pulsar is part of a binary system, based on the differences in its spin frequency (revolutions per second) between the original detection and follow-up observations.

"Pulsars are some of the most extreme objects in the universe," said Joe Swiggum, a graduate student in physics and astronomy at West Virginia University in Morgantown and lead author on a paper accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal explaining this result and its implications. "The students' discovery shows one of these objects in a really unique set of circumstances."

Optical telescope surveys of the same area of the sky, however, revealed no visible companion - which would have been clearly seen if it were a white dwarf star or main sequence star. "Given the lack of any visible signals and the careful review of the timing of the pulsar, we concluded that the most likely companion was another neutron star," said Swiggum.

Further analysis of the timing of the pulses indicates that the two neutron stars have the widest separation ever observed in a double neutron star system.

Some pulsars in double neutron star systems are so close to their companion that their orbital paths are comparable to the size of our Sun and they make a full orbit in less than a day. The orbital path of J1930-1852 spans about 52 million kilometers, roughly the distance between Mercury and the Sun and it orbits its companion once every 45 days. "Its orbit is more than twice as large as that of any previously known double neutron star system," said Swiggum. "The pulsar's parameters give us valuable clues about how a system like this could have formed. Discoveries of outlier systems like J1930-1852 give us a clearer picture of the full range of possibilities in binary evolution."

"This experience taught me that you do not have to be an 'Einstein' to be good at science," said McGough, who is now a Schreyer Honors College scholar at Penn State University in State College majoring in astronomy and astrophysics and physics. "What you have to be is focused, passionate, and dedicated to your work."

Comments