Titan, the most famous moon around Saturn, has an atmosphere that is a brownish-orange haze. The dirty color comes from a mixture of hydrocarbons, molecules that contain hydrogen and carbon, and nitrogen-carrying chemicals called nitriles. The family of hydrocarbons already has hundreds of thousands of members, identified from plants and fossil fuels on Earth, and even more could exist.

Researchers recently set out to simulate Titan's chemistry. In doing so, the team was able to classify a previously unidentified material discovered by NASA's Cassini spacecraft in the moon's smoggy haze.

The logical starting point was to begin with the two gases most plentiful in Titan's atmosphere: nitrogen and methane. But these experiments never produced a mixture with a spectral signature to match to the one seen by Cassini; neither have similar experiments conducted by other groups. Like reverse engineering anything complex, the starting possibilities were almost limitless.

To figure it all out, the researchers turned to the tried-and-true approach of combining gases in a chamber and letting them react. The idea is that if the experiment starts with the right gases and under the right conditions, the reactions in the lab should yield the same products found in Titan's smoggy atmosphere. The process is like being given a slice of cake and trying to figure out the recipe by tasting it. If you can make a cake that tastes like the original slice, then you chose the right ingredients.

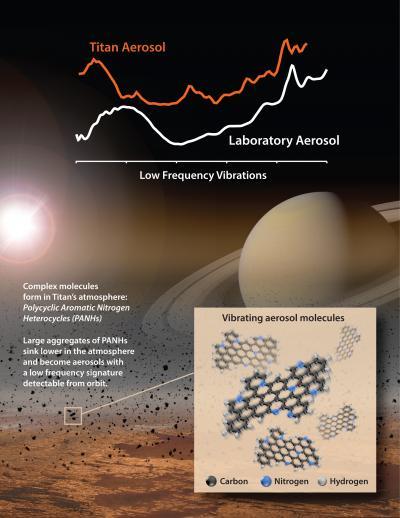

Scientists matched the spectral signature of an unknown material the Cassini spacecraft detected in Titan's atmosphere at far-infrared wavelengths. The material contains aromatic hydrocarbons that include nitrogen, a subgroup called polycyclic aromatic nitrogen heterocycles. Credit: NASA/Goddard/JPL

Promising results finally came when the researchers added a third gas, essentially tweaking the flavors in the recipe for the first time. The team began with benzene, which has been identified in Titan's atmosphere, followed by a series of closely related chemicals that are likely to be present there. All of these gases belong to the subfamily of hydrocarbons known as aromatics.

The outcome was best results were obtained when the scientists chose an aromatic that contained nitrogen. When team members analyzed those lab products, they detected spectral features that matched up well with the distinctive signature that had been extracted from the Titan data by Carrie Anderson, a Cassini participating scientist at Goddard and a co-author on this study.

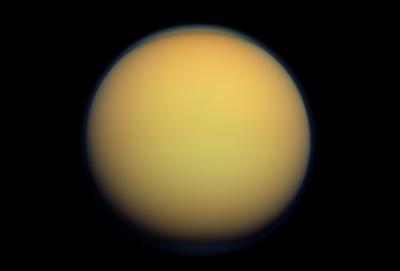

Titan's atmosphere makes Saturn's largest moon look like a fuzzy orange ball in this natural-color view from the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini captured this image in 2012. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

"Now we can say that this material has a strong aromatic character, which helps us understand more about the complex mixture of molecules that makes up Titan's haze," said Melissa Trainer, a planetary scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The material had been detected earlier in data gathered by Cassini's Composite Infrared Spectrometer, an instrument that makes observations at wavelengths in the far infrared region, beyond red light. The spectral signature of the material suggested it was made up of a mixture of molecules.

"This is the closest anyone has come, to our knowledge, to recreating with lab experiments this particular feature seen in the Cassini data," said Joshua Sebree, the lead author of the study, available online in Icarus. Sebree is a former postdoctoral fellow at Goddard who is now an assistant professor at the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls.

Now that the basic recipe has been demonstrated, future work will concentrate on tweaking the experimental conditions to perfect it.

"Titan's chemical makeup is veritable zoo of complex molecules," said Scott Edgington, Cassini Deputy Project Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "With the combination of laboratory experiments and Cassini data, we gain an understanding of just how complex and wondrous this Earth-like moon really is."

This Cassini image from 2012 shows Titan and its parent planet Saturn. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

Comments