Last winter's curvy jet stream pattern brought mild temperatures to western North America and harsh cold to the East and it may have seemed exceptional in the era of 24-hour news, but it's been happening that way for about 4,000 years, according to a new study.

It is not new for scientists to forecast that the current warming of Earth's climate due to carbon dioxide, methane and other "greenhouse" gases already has led to increased weather extremes and will continue to do so. The new study is based mainly on isotope ratios at Buckeye Creek Cave, W. Va.; Lake Grinell, N.J.; Oregon Caves National Monument; and Lake Jellybean, Yukon. Additional data supporting increasing curviness of the jet stream over recent millennia came from seven other sites: Crawford Lake, Ontario; Castor Lake, Wash.; Little Salt Spring, Fla.; Estancia Lake, N.M.; Crevice Lake, Mont.; and Dog and Felker lakes, British Columbia. Some sites provided oxygen isotope data; others showed changes in weather patterns based on tree ring growth or spring deposits.

The new paper shows the jet stream pattern that brings North American wintertime weather extremes is millennia old – a longstanding and persistent pattern of climate variability. Obviously climate instability may enhance the pattern so there will be more frequent or more severe winter weather extremes or both.

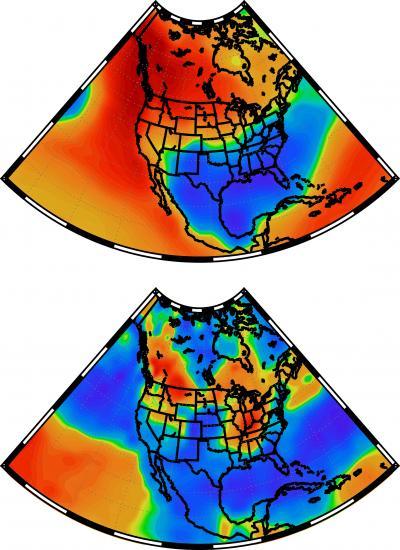

These maps show winter temperature patterns (top) and winter precipitation patterns (bottom) associated with a curvy jet stream (not shown) that moves north from the Pacific to the Yukon and Alaska, then plunges down over the Canadian plains and into the eastern United States. A University of Utah-led study shows that starting 4,000 years ago, the jet stream tended to become curvier than it was between 8,000 and 4,000 years ago, and suggests global warming will enhance such curviness and thus frigid weather in the eastern states similar to this past winter's. The curvy jet stream brought abnormally warm temperatures (red and orange) to the West and Alaska and an abnormal deep freeze (blue) to the East this past winter, similar to what is shown in the top map, except the upper Midwest was colder than shown. The bottom map of a typical curvy jet stream precipitation pattern shows how that normally brings dry winters to reddish-orange areas and wet winters to blue regions. Precipitation patterns this winter matched the bottom map in many regions, except California was drier than expected and the upper Midwest was wetter than expected. Credit: Zhongfang Liu, Tianjin Normal University, China.

"This is one more reason why we may have more winter extremes in North America, as well as something of a model for what those extremes may look like," says geochemist Gabe Bowen, associate professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah and senior author of the paper in Nature Communications. "We saw a good example of extreme wintertime climate that largely fit that pattern this past winter," although in the typical pattern California often is wetter. The authors note that human-caused climate change is reducing equator-to-pole temperature differences; the atmosphere is warming more at the poles than at the equator. Based on what happened in past millennia, that could make a curvy jet stream even more frequent and-or intense than it is now.

The researchers analyzed previously published data on oxygen isotope ratios in lake sediment cores and cave deposits from sites in the eastern and western United States and Canada. Those isotopes were deposited in ancient rainfall and incorporated into calcium carbonate. They reveal jet stream directions during the past 8,000 years, a geological time known as middle and late stages of the Holocene Epoch.

Next, the researchers did computer modeling or simulations of jet stream patterns – both curvy and more direct west to east – to show how changes in those patterns can explain changes in the isotope ratios left by rainfall in the old lake and cave deposits.

They found that the jet stream pattern – known technically as the Pacific North American teleconnection – shifted to a generally more "positive phase" – meaning a curvy jet stream – over a 500-year period starting about 4,000 years ago. In addition to this millennial-scale change in jet stream patterns, they also noted a cycle in which increases in the sun's intensity every 200 years make the jet stream flatter.

University of Utah geochemist Gabe Bowen.

Credit: Lee J. Siegel, University of Utah.

Sinuous Jet Stream Brings Winter Weather Extremes

The Pacific North American teleconnection, or PNA, "is a pattern of climate variability" with positive and negative phases, Bowen says.

"In periods of positive PNA, the jet stream is very sinuous. As it comes in from Hawaii and the Pacific, it tends to rocket up past British Columbia to the Yukon and Alaska, and then it plunges down over the Canadian plains and into the eastern United States. The main effect in terms of weather is that we tend to have cold winter weather throughout most of the eastern U.S. You have a freight car of arctic air that pushes down there."

Bowen says that when the jet stream is curvy, "the West tends to have mild, relatively warm winters, and Pacific storms tend to occur farther north. So in Northern California, the Pacific Northwest and parts of western interior, it tends to be relatively dry, but tends to be quite wet and unusually warm in northwest Canada and Alaska."

This past winter, there were times of a strongly curving jet stream, and times when the Pacific North American teleconnection was in its negative phase, which means "the jet stream is flat, mostly west-to-east oriented," and sometimes split, Bowen says. In years when the jet stream pattern is more flat than curvy, "we tend to have strong storms in Northern California and Oregon. That moisture makes it into the western interior. The eastern U.S. is not affected by arctic air, so it tends to have milder winter temperatures."

The jet stream pattern – whether curvy or flat – has its greatest effects in winter and less impact on summer weather, Bowen says. The curvy pattern is enhanced by another climate phenomenon, the El Nino-Southern Oscillation, which sends a pool of warm water eastward to the eastern Pacific and affects climate worldwide.

Traces of Ancient Rains Reveal Which Way the Wind Blew

Over the millennia, oxygen in ancient rain water was incorporated into calcium carbonate deposited in cave and lake sediments. The ratio of rare, heavy oxygen-18 to the common isotope oxygen-16 in the calcium carbonate tells geochemists whether clouds that carried the rain were moving generally north or south during a given time.

Previous research determined the dates and oxygen isotope ratios for sediments in the new study, allowing Bowen and colleagues to use the ratios to tell if the jet stream was curvy or flat at various times during the past 8,000 years.

Bowen says air flowing over the Pacific picks up water from the ocean. As a curvy jet stream carries clouds north toward Alaska, the air cools and some of the water falls out as rain, with greater proportions of heavier oxygen-18 falling, thus raising the oxygen-18-to-16 ratio in rain and certain sediments in western North America. Then the jet stream curves south over the middle of the continent, and the water vapor, already depleted in oxygen-18, falls in the East as rain with lower oxygen-18-to-16 ratios.

When the jet stream is flat and moving east-to-west, oxygen-18 in rain is still elevated in the West and depleted in the East, but the difference is much less than when the jet stream is curvy.

By examining oxygen isotope ratios in lake and cave sediments in the West and East, Bowen and colleagues showed that a flatter jet stream pattern prevailed from about 8,000 to 4,000 years ago in North America, but then, over only 500 years, the pattern shifted so that curvy jet streams became more frequent or severe or both. The method can't distinguish frequency from severity.

Simulating the Jet Stream

As a test of what the cave and lake sediments revealed, Bowen's team did computer simulations of climate using software that takes isotopes into account.

Simulations of climate and oxygen isotope changes in the Middle Holocene and today resemble, respectively, today's flat and curvy jet stream patterns, supporting the switch toward increasing jet stream sinuosity 4,000 years ago.

Why did the trend start then?

"It was a when seasonality becomes weaker," Bowen says. The Northern Hemisphere was closer to the sun during the summer 8,000 years ago than it was 4,000 years ago or is now due to a 20,000-year cycle in Earth's orbit. He envisions a tipping point 4,000 years ago when weakening summer sunlight reduced the equator-to-pole temperature difference and, along with an intensifying El Nino climate pattern, pushed the jet stream toward greater curviness.

Comments