Every once in a while I feel compelled to write in clear what should be self-evident to anybody with a working brain; to give a sort of "advice to surfers". I don't expect that such an advice be taken seriously - nobody wants to be told what to read and what to avoid - but at least it is posted, can be referred to, and it provides a sort of "disclaimer of liability".

Writing a serious blog, i.e. one that informs with continuity one audience and provides a true service, is already quite a demanding task; having to cope with the aftermath of articles that may inflame some readers, or with out-of-topic comments, or with the anger of whomever happens to feel outraged or offended, is sometimes too much. Hence the wish to keep that extra work at a minimum, manageable level.

One year has passed since the joint discovery, by the CMS and ATLAS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, of a particle which perfectly fits our expectations for a Standard Model Higgs boson. Highly wanted and sought for at particle colliders since the seventies, the Higgs boson is now an established reality, and the interest of experimental physicists has moved to a detailed study of the observable properties of this particle.

Yesterday I had the great pleasure to listen to George Zweig, who gave seminar about the discovery of the idea of quarks (or Aces, as he originally named them) at the International Conference of New Frontiers in Physics which is going on this week in the nice setting of Kolymbari, on the north-west coast of the Mediterranean island of Crete.

As few of my readers know, I have run a blog written in Greek language in parallel with this one for a couple of years. The idea of that endeavour was twofold: to offer some particle physics outreach in Greek language in the blogosphere, which is difficult to find, and to perfect my writing skills in that language.

The translation job was entertaining but difficult, and I finally gave up for lack of time, so that blog went in a hybernation state for a couple of years. But not any longer - I found a physics student who volunteered to continue the translation job, picking articles from this blog and translating them in Greek for Greek readers.

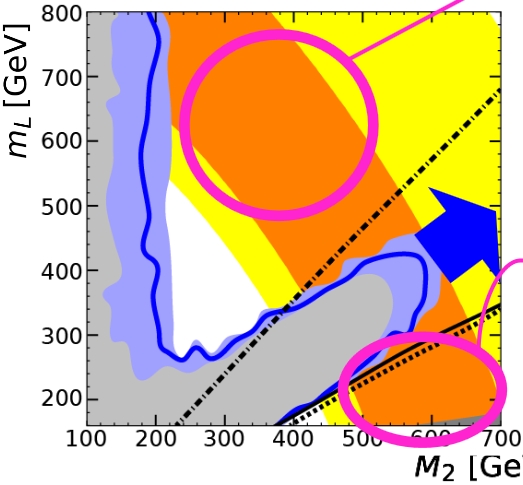

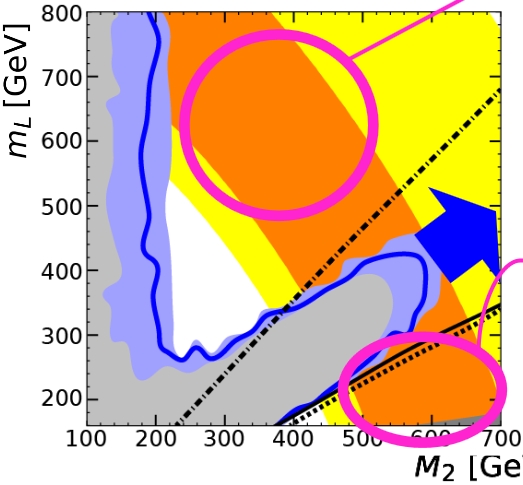

Thanks to a friend and follower of this blog, which I will not name for once to protect him from your flaming, I can share today with you one of the best instances of involuntary humor in particle physics graphs I have ever seen in my whole life.

The graph appears to be genuine, so this is a good candidate for the IgNobel prize IMHO.

Back from the beautiful Greek island of Naxos, I find myself in Venice for just a day before leaving to another Greek island - Crete. But this time for business rather than vacations: I will be giving a CMS Overview talk at the International Conference of New Frontiers in Physics, which started yesterday in Kolympari, on the north-western coast of the island.

As usual, I am lagging behind with the task of putting together my presentation slides. This time I had been working at a reasonable pace while on vacation, and I thought I was almost done, when I was notified that due to the absence of the CMS colleague who was in charge of speaking about CMS Heavy Ion Results, I was to cover in more detail that part than I would have.

Living At The Polar Circle

Living At The Polar Circle Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society

Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research

USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World

Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World