Scientific happenings, big and small, on this day in history.

For today’s quiz you’ll not only need to know a bit about science history, but need to have some familiarity with our military history as well. Which American aeronautics pioneer, born on this day in 1834, is the namesake for the Virginia military base that houses the United States Air Force’s 1st Fighting Wing? It’s not that hard really. Seriously, how many Virginia military bases do you know? But just to be sure, you can check the answer at the end of this article.

And more on this day in science…

EVENTS

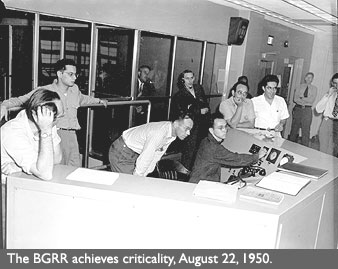

1950

The Brookhaven Graphite Research Reactor (BGRR) first reaches criticality

The Brookhaven Graphite Research Reactor was the first peace-time reactor to be constructed in the United States following World War II. The reactor's primary mission was to produce neutrons for scientific experimentation and refine reactor technology.

For a reactor to reach criticality, or a self-sustaining chain reaction, there must be a balance between the rate at which neutrons are produced by fission and the rate at which they are lost (by causing further fission, by absorption by the surrounding materials, or by leaving the core). When the rate of production of neutrons equals the rate of loss, the reaction is said to be critical. This is the operating state of a reactor. If the losses are higher, the reaction dies away. In the opposite case, an uncontrollable chain reaction could be established and the core may melt leading to what is popularly known as meltdown.

In a research reactor like the BGRR, neutrons are captured by uranium nuclei in the fuel elements, causing some of them to undergo fission. Resulting from the fission process are two large nuclear fragments and two to three neutrons. These neutrons are available to initiate new fission events. If, on the average, one of the neutrons from a fission produces another fission, a chain reaction is said to take place. Neutrons which do not cause additional fission reactions and which are not absorbed by the reactor itself are available for experiments. The BGRR was constructed like a cube, with three sides and the top of the cube available for the insertion of experiments which would be irradiated by these neutrons.

The BGRR provided 18 years of service before it was placed on standby in June 1968 and then permanently shutdown. Final decommissioning of the BGRR was begun in the late 1990s.

http://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/history/BGRR.asp

1962

World’s first nuclear-powered ship completes maiden voyage

The Savannah, the world's first nuclear-powered cargo-passenger ship, completed her maiden voyage from Yorktown, VA to Savannah, GA on August 22, 1962.

In a world terrified by the prospect of nuclear war, the Savannah was meant to demonstrate the peaceful use and positive potential of nuclear power. President Eisenhower conceived the idea as part of his "Atoms for Peace” program in 1955, a time when the United States and Soviet Union were routinely testing increasingly powerful nuclear weapons.

The Savannah, named for the first steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean in 1819, was in every sense of the word a showcase. The ship was given a sleek, streamlined design that wasn't really compatible with stowing large amounts of cargo; a fact that would eventually shorten its career.

Passenger accommodation was comparable to many conventional liners of the day. There were 30 air-conditioned staterooms, a dining room for 100 people, a swimming pool, a library and a lounge that could be converted into a cinema.

But the heart of the Savannah was its nuclear propulsion system, which at $28 million ($203 million in today's money) cost more than the ship itself, a mere $18.5 million ($134 million today). The Babcock and Wilcox nuclear reactor drove Savannah's two steam-turbine engines cheaply and efficiently.

In the end, though, it wasn't economical enough to offset the tight forward cargo area and other deficiencies that made the ship too expensive to operate commercially. Its tapered bow not only limited the cargo capacity to 8,500 tons -- well below that of contemporary vessels -- but also made loading difficult, especially as ports became more automated.

The Maritime Administration, which owned Savannah, leased her in 1965 to American Export-Isbrandtsen Lines for cargo-passenger service. But the ship never turned a profit and was laid up in January 1972. The Savannah spent most of the 1970s tied up in Galveston, Texas, where it underwent regular inspections of its nuclear plant.

Recently, The Savannah moved to its new home in a Baltimore where it will be docked "in safe store" on the Patapsco River until Congress appropriates money to finish scrubbing its nuclear innards.

All nuclear fuel was removed 30 years ago, but tainted equipment and components remain on board, surrounded by 24-inch-thick concrete. The ship still emits low-grade radiation, but at levels comparable to a dental X-ray, according to the Maritime Administration. Such scrubbing had been a priority after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, when fears were raised that radicals might blow up the Savannah. But subsequent tests showed lower radiation levels than were expected and budget priorities shifted.

The Savannah has been designated a National Historic Landmark, and when the cleanup job is completed sometime in 2011, the Maritime Administration hopes to see Savannah converted into a floating museum.

http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2008/08/dayintech_0822

http://www.wvec.com/news/topstories/stories/wvec_local_050708_savannah_leaves.d84b72e8.html

1968

X-15 Rocket Plane achieves world record altitude

The North American X-15 rocket-powered aircraft was part of the X-series of experimental aircraft, initiated with the Bell X-1. The X-15 set speed and altitude records in the early 1960s, reaching the edge of outer space and returning with valuable data used in aircraft and spacecraft design.

During X-15 Flight 91 on August 22nd, pilot Joe Walker reached a record-breaking 67 mile altitude (107.96 km). In the United States there are two definitions of how high a person must go to be referred to as an astronaut. The USAF decided to award astronaut wings to anyone who achieved an altitude of 50 miles (80.47 km) or more. However the FAI set the limit of space at 100 km. By either measure, Joe Walker met the mark on this day, joining the NASA astronauts and Soviet Cosmonauts as the only men to have crossed the barrier into outer space.

Flight 91 was the final X-15 flight over 100 km, highest altitude achieved by X-15, and the last flight for Walker in X-15 program. The X-15 is now on display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X-15

1989

Full rings discovered around Neptune

In the summer of 1989, NASA's Voyager 2 became the first spacecraft to observe the planet Neptune, its final planetary target. Passing about 4,950 kilometers (3,000 miles) above Neptune's north pole, Voyager 2 made its closest approach to any planet since leaving Earth 12 years earlier. Five hours later, Voyager 2 passed about 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) from Neptune's largest moon, Triton, the last solid body the spacecraft will have an opportunity to study.

As Voyager 2 approached Neptune, scientists had been working on theories of how partial rings, or ring arcs, could exist. Most settled for the concept of shepherding satellites that herd ring particles between them, keeping the particles from either escaping to space or falling into the planet's atmosphere. This theory had explained some new phenomena observed in the rings of Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus.

When Voyager 2 was close enough, its cameras photographed three bright patches that looked like ring arcs. But closer approach, higher resolution and more computer enhancement of the images showed that the rings do, in fact, go all the way around the planet. The rings are so diffuse, and the material in them so fine, that Earthbound astronomers simply hadn't been able to detect the full rings.

http://www.solarviews.com/eng/vgrnep.htm

BIRTHS

1844

George Washington DeLong (Born Aug. 22, 1844; Died Oct, 31, 1881)

DeLong was an ill-fated American explorer, made famous by his disastrous Arctic expedition.

Born in New York City, he was educated at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis Maryland. In 1879, backed by the owner of the New York Herald newspaper, and under the auspices of the US Navy, Lieutenant Commander DeLong sailed from San Francisco, CA on the ship USS Jeannette with a plan to find a quick way to the North Pole via the Bering Strait.

As well as collecting scientific data and animal specimens, De Long discovered and claimed three islands (De Long Islands) for the United States in the summer of 1881.

Unfortunately, his ship became trapped in the ice and eventually was crushed and sank. DeLong and his crew abandoned ship and set out for Siberia in three small boats. After reaching open water, they became separated and one boat was lost; no trace of it was ever found. DeLong's own boat reached land, but only two men sent ahead for aid survived. The third boat, under the command of Chief Engineer George W. Melville, reached the Lena delta and was rescued.

DeLong died of starvation near Mat Vay, Yakutsk, Siberia. Melville returned a year later and found the body of DeLong and his boat crew. Overall, the doomed voyage took the lives of nineteen expedition members, as well as additional men lost during the search operations.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_W._DeLong

1920

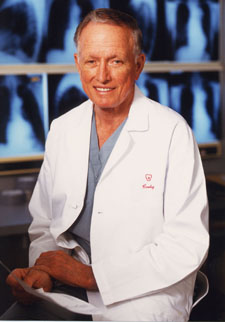

Denton Cooley (Born Aug. 22, 1920)

Cooley is an American surgeon and heart-transplant pioneer who was the first to implant an artificial heart in a human.

In 1941, he entered the Texas College of Medicine at Galveston, but soon transferred to Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. He obtained his M.D. degree in 1944 and remained at Hopkins as an intern, assisting Dr. Alfred Blalock in the first "blue baby" operation, to correct an infant's congenital heart defect.

Cooley believes the modern era in cardiovascular surgery began with Dr. Blalock's work, and it inspired him to specialize in heart surgery. Even as an intern, Cooley impressed his colleagues with his extraordinary speed and dexterity in the operating room.

On May 3, 1968, Cooley performed his first human heart transplant. The donor was a 15 year-old girl who had committed suicide. Although her brain had ceased to function, her heart was still beating. Cooley successfully transplanted the heart into a 47 year-old man, who survived for 204 days with the transplanted heart. Over the next year, Cooley performed 22 heart transplants, completing three within a single five-day period.

Cooley's extraordinary record in these years attracted both praise and criticism. Many Americans did not accept the end of brain activity as the moment of death, and condemned the practice of removing a beating heart for transplant. In 1969, with no donor heart available for his dying patient, Dr. Cooley took a great risk by implanting an experimental artificial heart. After 65 hours, a human heart became available, and Cooley replaced the artificial heart, but the patient died a day later.

Dr. Cooley and his wife Louise have raised five daughters. Dr. Cooley spends his limited spare time with his family, playing golf and playing upright bass with his all physician band, The Heartbeats.

http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/coo0bio-1

DEATHS

1828

Franz Joseph Gall (Born Mar. 9, 1758; Died Aug. 22, 1828)

Gall is rightfully recognized as a great anatomist, pioneering the concepts of localized functions in the brain. Around 1800, he developed "cranioscopy", a method to divine the personality and development of mental and moral faculties on the basis of the external shape of the skull. Cranioscopy (cranium=skull, scopos=vision) was later renamed to phrenology (phrenos=mind, logos=study) by his followers. Phrenolog, has long been abandoned as a “science”, but played an important role as a precursor to modern doctrines of brain localizations. This concept was proved correct when the French surgeon Paul Broca demonstrated the existence of a speech centre in the brain in 1861. It was soon also proved, however, that, as the thickness of the skull varies, the surface of the cranium does not reflect the topography of the brain. Thus the basic thesis of phrenology was disproved.

As a medical scientist Gall is recognized as the first to identify the grey matter of the brain with active tissue – neurons - and the white matter with conducting tissue - ganglia.

http://www.whonamedit.com/doctor.cfm/1018.html

1967

Gregory Pincus (Born Apr. 9, 1903; Died Aug. 22, 1967)

Pincus is best known for his central role in developing "the pill" oral contraceptive, or birth control pill.

Since the discovery of the sex hormones, scientists had searched for a natural, safe, and foolproof method of using female hormones to treat infertility and prevent pregnancy. Several scientists beginning in the 1920s showed that progesterone inhibited ovulation.

In 1934, at age 31, Pincus made national headlines by achieving in-vitro fertilization of rabbits. Pincus was decades ahead of his time. But instead of fame, the accomplishment brought notoriety. Aldous Huxley's novel Brave New World had just been published, and the nightmarish story of "fatherless" test tube babies born with no humanity or spirit had captured the public's imagination. Pincus was vilified in the press for his discovery, depicted as a "Dr. Frankenstein" who was turning science fiction into reality.

When Sanger and McCormick approached Pincus in 1953 about developing a new form of contraception, he was confident he could deliver. Pincus was aware of a study showing that progesterone could work as an effective anti-ovulent, and he had a hunch it would prove to be a good contraceptive drug. With funding from McCormick, in a matter of months Pincus and his colleague Min-Chueh Chang proved that repeated injections of progesterone stopped ovulation in animals.

Pincus's work attracted the attention of Margaret Sanger, the United States' best-known advocate of birth control. Financed by Sanger's friend, philanthropist Katherine Dexter McCormick (1875-1967), Pincus led a group of scientists in the early 1950s who began developing a hormone-based substance to make the body mimic pregnancy--the one time when a woman is almost certain not to become pregnant. The biologist Min-Chueh Chang carried out experiments on laboratory animals with various compounds of progestin, a synthetic progesterone. Another collaborator, physician John Rock, had already been experimenting with progesterone to cure infertility. Tests of the new substance on women took place in Massachusetts, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Mexico, and California, supervised by Pincus, Rock, Celso-Ramon Garcia and Edris Rice-Wray.

Because contraception was illegal in Massachusetts and due to objections from religious groups--principally the Roman Catholic Church--the initial tests were to treat infertility rather than prevent pregnancy. However, these tests showed that the compound prevented ovulation and in 1960, progesterone was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as the first contraceptive pill.

http://www.faqs.org/health/bios/86/Gregory-Pincus.html

1980

James S. McDonnell (Born Apr. 9, 1899; Died 22 Aug 1980)

James McDonnell was an aviation pioneer and founder of McDonnell Aircraft Corporation.

He graduated from Little Rock High School in 1917, just as World War I broke out. McDonnell served briefly as a private in the Army and then attended Princeton University, from which he graduated with honors in physics in 1921. While in college, he joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

After Princeton, he enrolled at Massachusetts Institute of Technology for graduate studies in aeronautical engineering. McDonnell recognized the need for an engineer to know how to fly an airplane. While still at MIT, he continued his ROTC affiliation, passed the Army Air Service physical and passed much of the ground-school work required for pilots. In August 1923, McDonnell was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army Air Service Reserve and assigned to Brooks Field, Texas, for flight training. He graduated from MIT in 1925. After earning his pilot's wings, McDonnell spent a year as a "gypsy pilot," doing odd jobs for people who owned airplanes.

He landed a job as aeronautical engineer and pilot with Huff Daland Airplane Co. in Ogdensburg, N.Y. In 1928, McDonnell started his first company to build the single Doodlebug, but since it found no market, he spent the next 10 years working for several aircraft companies, finally as a chief engineer with the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Co.

McDonnell resigned from Martin in 1938, determined to form his own company. On July 6, 1939, he incorporated the McDonnell Aircraft Corp. in St. Louis, Mo. Within the next three decades, the company would become the leading producer of jet fighters and would build the first spacecraft to carry an American into orbit. By the mid-1960s, McDonnell Aircraft Corp. was the largest employer in Missouri, and in 1967, it expanded its operation by merging with the largest employer in California, the Douglas Aircraft Co.

1950, he founded the James S. McDonnell Foundation to "improve the quality of life," The Foundation has pursued his goals by supporting scientific, educational, and charitable causes locally, nationally, and internationally. Since its inception, the McDonnell Foundation has awarded over $310 million in grants.

http://www.boeing.com/history/mdc/mcdonnell.htm

And the answer to today’s quiz?

The aeronautics pioneer, born on this day in 1834, who is the namesake for the Virginia military base that houses the United States Air Force’s 1st Fighting Wing:

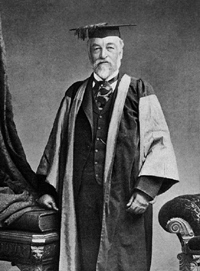

Samuel Pierpont Langley (Born Aug. 22, 1834; Died Feb. 27, 1906)

Langley is best known for his attempts to build the first heavier-than-air flying machine.

Langley experienced his greatest success with unmanned aerodromes. In particular, his Aerodrome No. 6 flew 4,200 feet at about 30 mph on November 28, 1896. This unmanned tandem-wing craft employed a lightweight steam engine for propulsion. The wings were set at a distinct dihedral angle so that the craft was dynamically stable, capable of righting itself when disturbed by a sideways breeze. There was no method of steering this craft, nor would it have been easy to add any means to control the direction the craft flew.

From the success of No. 6, Langley was able to convince the War Department (a.k.a. Department of Defense) to contribute $50,000 toward the development of a person-carrying machine. The Smithsonian contributed a like sum towards Langley's efforts. Charles Manley developed an extraordinary radial-cylinder internal combustion engine that developed 52 horsepower for the man-carrying Great Aerodrome. Langley felt it would be safest to fly over water, so he spent almost half of his funds constructing a houseboat with a catapult that would be capable of launching his new craft.

The Great Aerodrome might have flown if Langley had chosen a more traditional means of launching the craft from the ground. The pilot still would have lacked any means of steering the plane, and so faced dangers aplenty. But it might have at least gotten into the air. Unfortunately, Langley chose to stick with his 'tried-and-true' approach of catapult launches. The plane had to go from a dead stop to the 60 m.p.h. flying speed in only 70 feet. The stress of the catapult launch was far greater than the flimsy wood-and-fabric airplane could stand. The front wing was badly damaged in the first launch of October 7, 1903. A reporter who witnessed the event claimed it flew "like a handful of mortar." Things went even worse during the second launch of December 9, 1903, where the rear wing and tail completely collapsed during launch. Charles Manley nearly drowned before he could be rescued from the wreckage and the ice-covered Potomac river.

The War Department, in its final report on the Langley project, concluded "we are still far from the ultimate goal, and it would seem as if years of constant work and study by experts, together with the expenditure of thousands of dollars, would still be necessary before we can hope to produce an apparatus of practical utility on these lines." Eight days after Langley's spectacular failure, a sturdy, well-designed craft, costing about $1000, struggled into the air in Kitty Hawk, defining for all time the moment when humankind mastered the skies.

In spite of 18 years of well-funded and concerted effort by Langley to achieve immortality, his singular contribution to the invention of the airplane was the pair of 30-lb aerodromes that flew in 1986.

Of course today Langley is a household name – although used most often in conjunction with the first military base built in the United States specifically for air power: Langley Air Force Base, VA.

http://invention.psychology.msstate.edu/i/Langley/Langley.html

Comments