It’s a pure survival story, one about the complete deterioration of society into a vicious, gritty state of no-holds-barred struggle after a nuclear and biological holocaust. Unlike many other post-apocalyptic novelists, Tucker doesn’t envision much society left at all after total destruction: there is no reversion to a pseudo-Native American tribal state, to early rural 19th century agrarianism, to feudalism, to a theocratic dystopia. A total Hobbesian (or Darwinian) state of nature prevails for decades after the catastrophe. Society does not rebuild.

It is a classic gritty survival tale, fairly explicit for 1952. Without the institutions of technological society, with people forced into bare survival, life becomes a struggle of everyone against everyone. There is little cooperation, and compassionate social relationships are constantly under strain. Tucker suggests that this self-focused survival instinct is only slightly hidden below the surface in normal society, and it quickly comes to the fore in a struggle to survive. Human nature is ruthless in a survival setting; the comforts of society, in which bare survival is not the primary urgency, fosters civilized social behavior that isn't possible otherwise.

It is a classic gritty survival tale, fairly explicit for 1952. Without the institutions of technological society, with people forced into bare survival, life becomes a struggle of everyone against everyone. There is little cooperation, and compassionate social relationships are constantly under strain. Tucker suggests that this self-focused survival instinct is only slightly hidden below the surface in normal society, and it quickly comes to the fore in a struggle to survive. Human nature is ruthless in a survival setting; the comforts of society, in which bare survival is not the primary urgency, fosters civilized social behavior that isn't possible otherwise.It’s easy to misread this book as the straightforward glorification of the self-reliant man with a gun, along the lines of Jerry Ahern’s The Survivalist series (which I eagerly devoured as a teenager). No offense intended to Ahern, but to read The Long Loud Silence this way to miss Tucker’s moving psychological story of a man becoming a monster, ending with a glint of possible redemption.

The story features Corporal Gary, a hardened WWII combat veteran who wakes up after a two-day binge to a bomb and plague devastated world. It turns out that the eastern U.S. has been completely devastated by various weapons of mass destruction, while everything west of the Mississippi has been largely spared. Unfortunately Gary, still in the Army, spent his birthday binge on the wrong side of the river, in Illinois. Assuming that all eastern survivors are contaminated with plague, the U.S. military has cordoned off everything east of the Mississippi. Anyone attempting to cross over is shot on sight.

The story features Corporal Gary, a hardened WWII combat veteran who wakes up after a two-day binge to a bomb and plague devastated world. It turns out that the eastern U.S. has been completely devastated by various weapons of mass destruction, while everything west of the Mississippi has been largely spared. Unfortunately Gary, still in the Army, spent his birthday binge on the wrong side of the river, in Illinois. Assuming that all eastern survivors are contaminated with plague, the U.S. military has cordoned off everything east of the Mississippi. Anyone attempting to cross over is shot on sight.At first Gary sees everything as a limited inconvenience. He’s sure the Army will take him back - he’s still a soldier, after all. He’s so sure of this that he abandons the woman he’s briefly hooked up with, as soon as he sees a chance to cross the river. After it’s clear that not even soldiers are being allowed across, Gary holds out the hope that after a few days... weeks... months... somebody in the government will take charge, come back east, and restore order, authority, and civilization.

This hope is gradually eroded as the months and then years go on, and as this hope erodes, and the ruthless competition for scarce resources persists, Gary becomes a monster in a society of monsters. He steadily loses the (admittedly largely self-interested) compassion he exhibited at the outset, until finally a completely horrifying experience (which I won’t give away) reveals to him that he has absolutely no hope of ever recovering his former self.

By the end (twenty years after the bombs fell), the survivalist society has completely destroyed all but the most hardened and heartless. Gary obtains food by hunting other hunters: he carries a quiet .22 rifle, which he uses to kill hunters who have just brought down game with noisier, larger caliber guns. Given the reduced population in the east, a functioning society could clearly have provided enough resources for all of the survivors, but in fact nobody has rebuilt anything.

Ironically, in this masculine book with no deep women characters, one that describes a society hostile to women, it is the women in the book who so clearly and crucially mark out the milestones in Gary’s transformation into a monster. These women are for the most part at a disadvantage in the brutal post-apocalyptic world Tucker envisions, and it’s not too out of character for them to latch on to men out of necessity. (In other words, I don't think the sex encounters in this book are simply gratuitous.)

The first woman who ties herself to Gary is the first living person Gary encounters after he wakes up from his binge. She’s young, frightened, and without much of an idea of what to do now except loot jewelry shops. Gary takes charge of the immediate necessities of survival for the two of them. (And later that night, when she’s too afraid to sleep in her own hotel room, she comes into Gary’s and “proves she’s nineteen”...) Unfortunately Gary dumps her shortly thereafter, as soon as he thinks there’s a chance the Army will take him back.

The first woman who ties herself to Gary is the first living person Gary encounters after he wakes up from his binge. She’s young, frightened, and without much of an idea of what to do now except loot jewelry shops. Gary takes charge of the immediate necessities of survival for the two of them. (And later that night, when she’s too afraid to sleep in her own hotel room, she comes into Gary’s and “proves she’s nineteen”...) Unfortunately Gary dumps her shortly thereafter, as soon as he thinks there’s a chance the Army will take him back.The next woman shares herself with Gary and another ex-soldier, who have set up winter quarters on the Gulf coast. But after the winter is over, this woman, who is now pregnant with somebody's baby, clearly prefers the other guy and Gary moves on. Yet another woman Gary spends months with is someone whose name he doesn’t even remember a few months later.

The turning point in Gary’s descent comes after he rescues a 12-year old girl from an assault. Out of gratitude, the girl’s father invites Gary to spend his winter on their well-stocked farm, as a sentry. They happen to have a radio, and at night Gary listens to broadcasts from across the river. The radio news finally convinces Gary that the government is never coming back east for the survivors, and when spring arrives, Gary, in spite of his warm feelings towards the girl and her family, turns his back on them and never shows any compassion again.

The book ends years later, in a slight plot twist that I won’t give away, with Gary, after more than a decade as a ruthless murderer, encountering against all odds the possibility of redemption through love.

The Long Loud Silence is one of the best post-apocalyptic novels in a decade full of them. In Tuckers vision, a society devastated by the most destructive weapons that science can devise does not simply become a pre-industrialized, non-technological society. It does not rebuild, and civil society is not restored. We have come too far in our reliance on technology to go back, and the only possible existence is one mutual self-destruction.

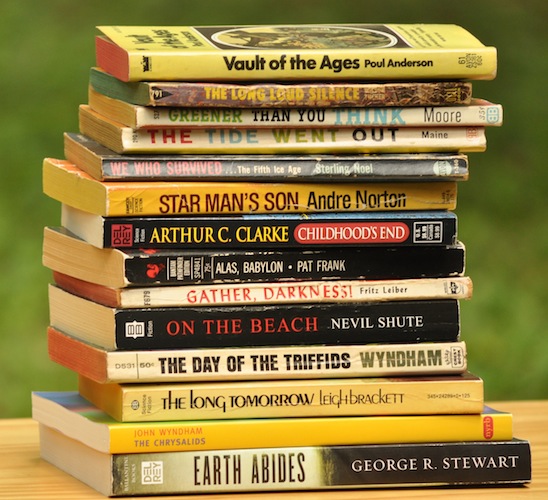

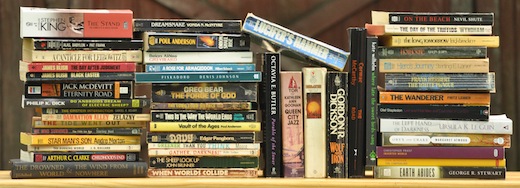

Next up in our our post-apocalyptic survey: a couple of 1952 post-nuclear tribal stories, Andre Norton's Star Man's Son, Poul Anderson's Vault of the Ages.

Read the feed:

Comments