The story is told via a rejected screenplay discovered by two friends on a Hollywood studio lot in 1947. All except the first section of the book consists of the text of the screenplay. The discarded script starts out by portraying post-World War II society as a civilization of vicious baboons. After a series of surrealistic scenes interspersed with dramatic pronouncements by a narrator, the baboon civilization destroys itself, and the story focuses on a post-apocalyptic dystopia in the vicinity of what used to be Los Angeles. A botanist, Dr. Albert Poole, is a member of a New Zealand expedition scouting out the west coast of a nuclear bomb-ravaged United States. (New Zealand survived the war unscathed.) Poole is out taking samples of plants when he’s taken captive by the natives, and finds that post-holocaust California society is now largely organized around a church devoted to Satan.

The story is told via a rejected screenplay discovered by two friends on a Hollywood studio lot in 1947. All except the first section of the book consists of the text of the screenplay. The discarded script starts out by portraying post-World War II society as a civilization of vicious baboons. After a series of surrealistic scenes interspersed with dramatic pronouncements by a narrator, the baboon civilization destroys itself, and the story focuses on a post-apocalyptic dystopia in the vicinity of what used to be Los Angeles. A botanist, Dr. Albert Poole, is a member of a New Zealand expedition scouting out the west coast of a nuclear bomb-ravaged United States. (New Zealand survived the war unscathed.) Poole is out taking samples of plants when he’s taken captive by the natives, and finds that post-holocaust California society is now largely organized around a church devoted to Satan. Huxley uses the book’s structure, a rejected screenplay written by an amateur writer, to express in a blunt and intentionally heavy-handed way a bitterly disillusioned and even nihilistic perspective on humanity. The script includes a narrator making melodramatic pronouncements, a long central monologue by one character laying out most of the book’s main ideas, and some extreme scenes of fairly obvious symbolism that aim for shock value. The characters are primarily caricatures. Writing a novel that imitates a piece of amateur fiction is clearly a risky move, since the result could easily be a genuinely bad book.

Yet for the most part Huxley is successful, largely due to his vivd and elegant prose. He also succeeds because the large, dramatic strokes of the novel are well matched to the subject matter. Huxley witnessed, within 35 years, two calamitous world wars, followed by the introduction of new weapons that promised to make the next world war orders of magnitude more destructive. Although post-apocalyptic fiction as a genre existed before the era of nuclear weapons, never before had the near-total annihilation of humanity been such a live possibility. Ape and Essence is a powerful response to the threat of nuclear destruction.

In the opening scenes of the script, scientists are portrayed as victims of an abusive relationship with society. A baboon in a dress is on a nightclub stage, accompanied by scientist Michael Faraday, who is on all fours and fixed to a leash. The baboon sings, and Faraday begins to cry. The scene ends with the baboon beating the humiliated scientist on stage as the audience roars with baboon laughter.

This is followed by scenes of various Baboon armies leading scientists like Einstein and Lavoisier around on leashes, as the baboons prepare to slaughter each other with biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons. The scientists aren’t portrayed merely as innocent victims; they are dupes, craving the approval of society. The script’s narrator comments:

Biologists, pathologists, physiologists - here they are, after a hard day at the lab, coming home to their families. A hug from the sweet little wife. A romp with the children. A quiet dinner with friends, followed by an evening of chamber music or intelligent conversation about politics or philosophy. Then bed at eleven and the familiar ecstasies of married love. And in the morning, after orange juice and Grapenuts, off they go again to their job of discovering how yet greater numbers of families precisely like their own can be infected with a yet deadlier strain of bacillus mallei.

After the baboon civilization commits suicide “by science”, two Einsteins lie disfigured and dying, lamenting to each other that they were only pursuing science in the quest for truth.

The central theme of the book is that there is a destructive paradox inherent in our pursuit of science and technology. We pursue the means to conquer nature under a guise of rationality, but our essence remains that of animals. The result is that we remain in an extreme Malthusian trap produced by our drive for technology and our drive for sex. This idea is fleshed out in a long, intentionally absurd discussion between captured New Zealand scientist Albert Poole and the Satan-worshiping Arch-Vicar of the Church of Belial. As the Arch-Vicar and Poole sit eating pig’s feet to the accompaniment screams coming from a ceremony of mass human sacrifice, Poole learns the philosophy underlying the Church of Belial:

The central theme of the book is that there is a destructive paradox inherent in our pursuit of science and technology. We pursue the means to conquer nature under a guise of rationality, but our essence remains that of animals. The result is that we remain in an extreme Malthusian trap produced by our drive for technology and our drive for sex. This idea is fleshed out in a long, intentionally absurd discussion between captured New Zealand scientist Albert Poole and the Satan-worshiping Arch-Vicar of the Church of Belial. As the Arch-Vicar and Poole sit eating pig’s feet to the accompaniment screams coming from a ceremony of mass human sacrifice, Poole learns the philosophy underlying the Church of Belial:As a man of science, you’re bound to accept the working hypothesis that explains the facts most plausibly. Well, what are the facts? The first is a fact of experience and observation - namely that nobody wants to suffer, wants to be degraded, wants to be maimed or killed. The second is a fact of history - the fact that, at a certain epoch, the overwhelming majority of human beings accepted beliefs and adopted courses of action that could not possibly result in anything but universal suffering, general degradation, and wholesale destruction. The only plausible explanation is that they were inspired or possessed by an alien consciousness, a consciousness that willed their undoing and willed it more strongly than they were able to will their own happiness and survival.

The Arch-Vicar explains that the influence of Satan began when, after 100,000 years of stalemate humans began to “turn the tide” in their battle with nature. With the rise of science humans became slaves to technology. Science and technology decoupled our sex drive from the limits of nature, resulting in a population explosion. As the planet gets crowded the only way the species can reduce its numbers and continue to survive is mass starvation or turning our technology towards war. And should we somehow manage to avoid both starvation and total war, our mistaken belief that we’ve conquered nature will eventually do us in, because some day nature will put is back in our place after we've pushed it too far out of balance.

And so the Satan-worshiping people of post-Holocaust California have reverted to an imitation of a natural state. Mating is seasonal (taking place during two weeks of free-for-all sex), and the population is kept in check by culling all of the mutant infants born that year in a human sacrifice ceremony that takes place immediately before mating season.

Dr. Poole begins as a straight-laced, non-sexual man of reason, until finally his experiences in this dystopian society unlock long-repressed sexual desires, and he participates wholeheartedly in the sexual festivities. Towards the end, Poole falls in love (or at least finds someone willing to keep having sex out of season), and is possibly on the verge of one more transformation, transcending the bestial, Belial-worshiping lifestyle he’s been living. Or else, as a scientist, he’s about to start the whole cycle of technological progress and destruction over again.

Ape and Essence is a work of satire and not philosophy, and thus not all of the arguments are meant to be taken literally. The absurdity of the Church of Belial mirrors the absurdity of a civilization that turns to nuclear weapons after two wars of unprecedented scope. Huxley’s not offering hopeful alternatives here; we’re hopelessly doomed by our essential nature. As a work of post-apocalyptic fiction, the book is a powerful exploration of the relationship between science and civilization that has brought humanity to the brink of near-total annihilation.

Postscript:

My library copy of this book has, pasted inside the cover, a 1948 newspaper clipping with quotes from reviews of Ape and Essence that are entertaining:

“On the aesthetic level, Huxley’s debits and credits remain fairly constant. On the one hand, a beautifully modulated, lucid, and incisive prose style; on the other, an incapacity to create characters who transcend the functions of targets, mouthpieces, and puppets... If ‘Ape and Essence’ adds nothing to Huxley’s stature as a novelist, it confirms again his sensitive, barometric relationship to his time.”

“Perhaps the Huxley name will carry this to a certain market, but for the average normal readers, this form of satire at its most explicit may well prove distasteful.”

“I found myself much more impressed by Mr. Huxley’s grand disgust with all of us alive today than by his wrathful movie of a twenty-first century reverting back to the Stone Age and worshiping the Devil.” (This last is by Alfred Kazin.)

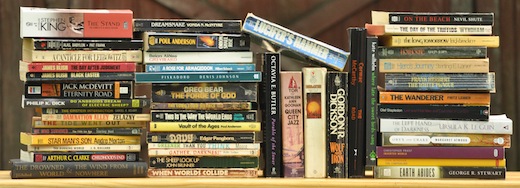

Next up in our chronological series of post-apocalyptic science fiction: A big post-apocalyptic classic, George Stewart's epic 1949 Earth Abides.

Read the feed:

Comments