Exactly what nuclear world war would look like was a matter of diverse opinion in the nuclear apocalypse novels of the 1950‘s.

Exactly what nuclear world war would look like was a matter of diverse opinion in the nuclear apocalypse novels of the 1950‘s.Many post-apocalyptic novels of this decade portrayed World War III as an essentially known if more extreme extension of the destructive experience of World War II, much the way that World War II was like World War I jacked up a notch.

At worst, large swaths of land would be rendered permanently uninhabitable for decades (The Long Tomorrow), centuries (The Chrysalids), or even millennia (Pebble in the Sky); nevertheless, the destruction of nuclear bombs was fundamentally the same as what came before. Death occurrs on a massive but not extinctive scale, and while there is some danger from fallout, the worst damage is primarily in those areas of direct hits. This was a logical view at the time - after all, the results of the bombing of Hiroshima, at first glance, weren't much different from the firebombing of Tokyo.

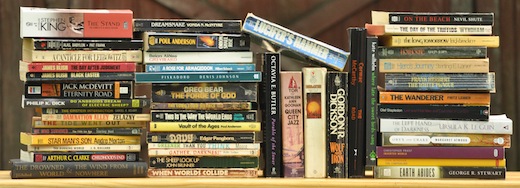

Along comes Nevil Shute in 1957 with a shocking book that thoroughly rejects the conventional picture of nuclear destruction. On The Beach doesn’t feature scenes of bombed-out cities or survivors picking their way through the skeletal remains of a civilization bombed out of existence. This books offers a much more horrifying picture: completely intact towns and cities in which everyone is dead. There are no living survivors in this book, in spite of the fact that homes, roads, bridges, rail lines, and office buildings remain unscathed.

For a book that concerns the end of all life on Earth, On The Beach is remarkably mild and relatively tension-free, even a little boring. The story centers on Melbourne, Australia, one of the world’s southernmost major cities. By virtue of geography, the residents of Melbourne are among the very last human inhabitants on an Earth dying of nuclear fallout. A brief but cataclysmic nuclear war wiped out the Northern Hemisphere, and the fallout has been gradually drifting south, extinguishing all life as it goes. The book’s characters, who have witnessed the more northern Australian cities fall silent one by one, know that their turn is coming. There will be no reprieve for the human species.

For a book that concerns the end of all life on Earth, On The Beach is remarkably mild and relatively tension-free, even a little boring. The story centers on Melbourne, Australia, one of the world’s southernmost major cities. By virtue of geography, the residents of Melbourne are among the very last human inhabitants on an Earth dying of nuclear fallout. A brief but cataclysmic nuclear war wiped out the Northern Hemisphere, and the fallout has been gradually drifting south, extinguishing all life as it goes. The book’s characters, who have witnessed the more northern Australian cities fall silent one by one, know that their turn is coming. There will be no reprieve for the human species.In the face of certain extinction, the residents of Australia are remarkably stoic. Society does not break down, and in fact hums along fairly smoothly as many people cope by behaving as if their lives will simply go on. They continue to make plans for the future, well past the time when they know the fallout will have inevitably settled on their region. People drink a little more (the members of an elite Melbourne private club race to finish off the club’s not insignificant stock of fine port before the end) and work a little less, but generally society goes on.

Unlike many other post-apocalyptic novels, On The Beach does not feature a dark side of human nature that is unleashed in the face of catastrophe. The pathology was in society as a whole, a society that was capable of knowingly wiping itself out. All of the individuals in the book are fundamentally decent people, and they remain that way, creating essentially a brief near-utopia. With limited time remaining, money doesn’t matter quite so much anymore. What does matter, to many people, is to keep life as normal as possible. Dwight Towers, captain of an American submarine, takes this principle to an extreme. He continues to maintain naval discipline and routine until the end, and turns down the opportunity for a quick, final but loving relationship with another woman because Towers behaves as if he were returning to his wife and two children in Connecticut after his tour is up.

Feeling some need to carry on some semblance of continuing operations, the Australian government sends Towers and his crew out on an observational mission to North America. Everyone figures that this trip will be relatively pointless in terms of information gained, but with the sub available it’s difficult not to so something. Towers takes his sub to the west coast of the former United States, where he spends a few weeks investigating what’s left. This tour of a lifeless Northern Hemisphere is one of the most compelling aspects of On The Beach. Viewed offshore through a periscope, nearly all of the coastal cities look just as they always have, except that nobody’s home. This, Shute is telling us, is what the aftermath of a nuclear war will really look like. Nuclear war won't send us back to the stone age. There will be no age of any kind, at least not one populated by humans.

Given that so little happens in this book, On The Beach is strangely compelling. I’m not sure why I wasn’t bored most of the time. Much of the dialogue was annoying, the characters were largely homogeneous and not very well developed. There is none of the savagery or ruthless survivalism that is typical of other post-apocalyptic novels. Shute’s shocking premise was enough to keep me reading. Nuclear war is not simply a more extreme of conventional war. It is something that can kill us without the inconvenient necessity of destroying our cities and towns in the process.

After a very long hiatus to deal with pressing research and a pain in the ass RSI, this series is back. Up next in the post-apocalyptic survey: A pulp nuclear eco-apocalypse, Charles Eric Maine's 1958 The Tide Went Out.

Read the feed:

Comments