John Christopher’s 1956 No Blade of Grass is an extremely compelling page turner that portrays our moral traditions and social glue as being so fragile that they can be swept away in a day. Compassion, mercy, and even friendliness are not as hard-wired as we would hope, and they quickly dissolve when the urgency of survival forces us to view all other people as competitors.

The plot line is an inversion of the grass catastrophe in Greener Than You Think. In Christopher’s book, an unstoppable ‘Chung-li’ virus is killing all grasses, which includes food staples like wheat and rice. The catastrophe begins far away in China, which makes it easy for the main protagonist, John Custance, and his fellow citizens in London to dismiss the crisis - it couldn’t possibly affect their solid, predictable society. Catastrophes happen in more exotic locations. But of course the virus spreads, decimating food stocks world wide, and threatening to render Britain’s green countryside a dusty wasteland. The British government comes up with a radical solution: reduce the population to a size they can feed. Rather than risk food riots and a starving populace, the government plans trim Britain’s population by cordoning off a few cities and dropping nuclear bombs. Or at least so the rumor goes. John gets an early tipoff, and decides to take his family and flee London for his brother’s countryside farm in a fortress-like valley. What they initially think will be a relatively short drive from London turns into a harrowing trek through a country populated by people who were friendly citizens last week, but are now deadly, merciless enemies.

The plot line is an inversion of the grass catastrophe in Greener Than You Think. In Christopher’s book, an unstoppable ‘Chung-li’ virus is killing all grasses, which includes food staples like wheat and rice. The catastrophe begins far away in China, which makes it easy for the main protagonist, John Custance, and his fellow citizens in London to dismiss the crisis - it couldn’t possibly affect their solid, predictable society. Catastrophes happen in more exotic locations. But of course the virus spreads, decimating food stocks world wide, and threatening to render Britain’s green countryside a dusty wasteland. The British government comes up with a radical solution: reduce the population to a size they can feed. Rather than risk food riots and a starving populace, the government plans trim Britain’s population by cordoning off a few cities and dropping nuclear bombs. Or at least so the rumor goes. John gets an early tipoff, and decides to take his family and flee London for his brother’s countryside farm in a fortress-like valley. What they initially think will be a relatively short drive from London turns into a harrowing trek through a country populated by people who were friendly citizens last week, but are now deadly, merciless enemies.No Blade of Grass features a common theme in post-apocalyptic fiction: nobody expects things to fall apart as quickly as they do. In the developed world, a world governed by the rule of law, by technology that provides us with stable food, shelter, and medical care, a world that’s inhabited by civilized people, we just can’t imagine the total deterioration of society - our scientific abilities will rescue us before things get too bad. We can’t imagine ourselves having to kill other people for our survival, or to callously turn aside a child who needs help. But when we’re surrounded by millions who need help, our circle of friendship constricts precipitously, and our compassion and mercy are reserved only those most close to us, or those who can prove helpful for survival.

1950’s survivalist End of the World fiction was written when many men in their 30’s were combat veterans of WWII, and therefore there are some interesting possibilities for creating characters who are suburban fathers, responsible citizens, and trained killers at the same time. John Custance’s party is led by himself and two other men, John’s war buddy and neighbor Roger, and a gun shop owner, Pirrie, who is the most ruthless survivalist of the group. Pirrie does not hesitate to recognize how dire the situation is, and is quick to pull the trigger. John, who is the reluctant leader of the group, and his wife, Anne, experience much more agony over the life and death decisions they have to make. At first, they can’t acknowledge how bad the situation is, although they are immediately making life and death decisions as they make their way out of London - they choose not to warn anyone about about the disaster that threatens. If they can get out before everyone else panics, they will improve their chances of survival.

1950’s survivalist End of the World fiction was written when many men in their 30’s were combat veterans of WWII, and therefore there are some interesting possibilities for creating characters who are suburban fathers, responsible citizens, and trained killers at the same time. John Custance’s party is led by himself and two other men, John’s war buddy and neighbor Roger, and a gun shop owner, Pirrie, who is the most ruthless survivalist of the group. Pirrie does not hesitate to recognize how dire the situation is, and is quick to pull the trigger. John, who is the reluctant leader of the group, and his wife, Anne, experience much more agony over the life and death decisions they have to make. At first, they can’t acknowledge how bad the situation is, although they are immediately making life and death decisions as they make their way out of London - they choose not to warn anyone about about the disaster that threatens. If they can get out before everyone else panics, they will improve their chances of survival.Soon enough, the party needs to kill to survive. A turning point comes when Anne, who has been a voice of conscience, kills an incapacitated assailant out of pure revenge. John and Anne keep telling themselves that life can revert to normal again when they’ve reached safety - their consciences will be recoverable. The books ends in a brutal plot twist that involves more killing than they expected, but holds out hope that once the dire situation has passed, compassion can reassert itself.

No Blade of Grass, like other novels written when the violence of World War II was still fresh and the possibility of nuclear annihilation was new and close, hammers away at our sense of security. “How long,” Custance wonders, “before the exploring Americans land at the forgotten harbors and push inland, handing out cigarettes, and scattering Chung-Li immune grass seed on their way?” But there will be no “last minute reprieve for mankind... Nature was wiping a cloth across the slate of human history, leaving it empty for the pathetic scrawls of those few who, here and there over the face of the globe, would survive.” Perhaps what’s most frightening about this book is the collapse of society before the physical crisis truly develops. The rumor, true or not, that the government is planning to bomb its citizens (and thus making the same kinds of ruthless survival decisions that John and his crew make on a smaller scale), combined with difficult but not impossible food shortages, is enough to spark a pre-emptive, vicious fight for survival.

No Blade of Grass, like other novels written when the violence of World War II was still fresh and the possibility of nuclear annihilation was new and close, hammers away at our sense of security. “How long,” Custance wonders, “before the exploring Americans land at the forgotten harbors and push inland, handing out cigarettes, and scattering Chung-Li immune grass seed on their way?” But there will be no “last minute reprieve for mankind... Nature was wiping a cloth across the slate of human history, leaving it empty for the pathetic scrawls of those few who, here and there over the face of the globe, would survive.” Perhaps what’s most frightening about this book is the collapse of society before the physical crisis truly develops. The rumor, true or not, that the government is planning to bomb its citizens (and thus making the same kinds of ruthless survival decisions that John and his crew make on a smaller scale), combined with difficult but not impossible food shortages, is enough to spark a pre-emptive, vicious fight for survival.Like The Road, No Blade of Grass explores how it is possible to be humane in a brutal society. How contingent is our humanity on our surroundings, on our safety, on our ability to live largely predictable lives that have been, by virtue of our technology, freed from the immediate urgencies of survival?

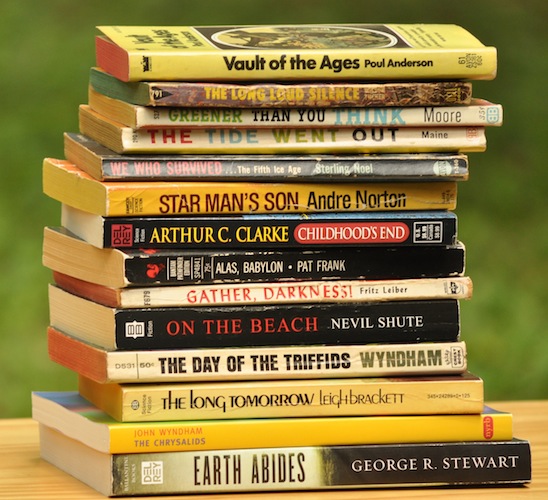

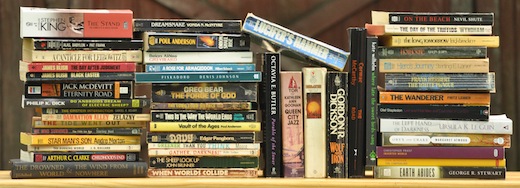

Next up in our post-apocalyptic survey: The most commonly read post-apocalyptic novel (perhaps after The Road - Nevil Shute's 1957 On The Beach.

Read the feed:

Comments