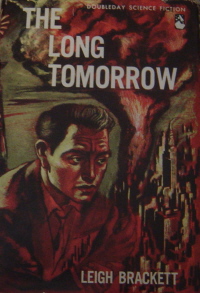

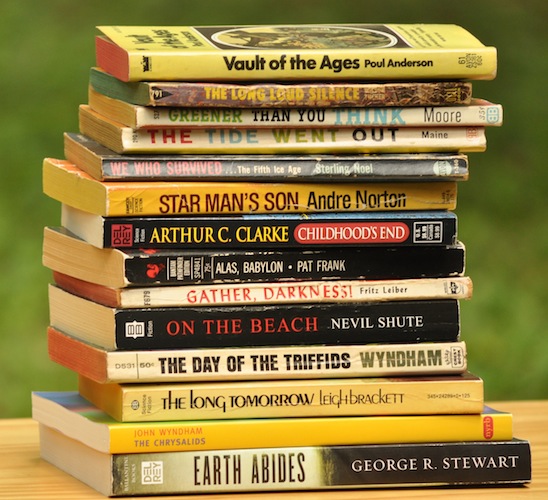

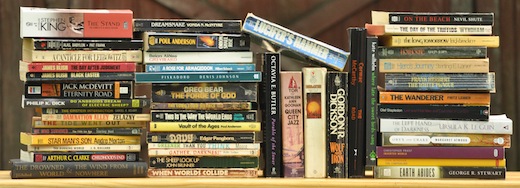

Leigh Brackett's The Long Tomorrow is one of many post-apocalyptic novels that envision society returned to a 19th century agrarian state. The rural settings of these novels are commonly used to explore life in a society driven by fear, fear or technology, or change, or those who are different. A society based on fear of technology is what Leigh Brackett explores here.

The Long Tomorrow tells the story of a North American society that, in the wake of nuclear devastation, became essentially Mennonite, since it was the Amish and the Mennonites who were able to adapt most effectively to a world without modern, 20th century technology. And thus Mennonite beliefs about technology, in some form or another, spread widely. Technology, curiosity about technology, and scientific knowledge (and the benefits of that knowledge) are frowned upon, and in some cases even punished severely.

The Long Tomorrow tells the story of a North American society that, in the wake of nuclear devastation, became essentially Mennonite, since it was the Amish and the Mennonites who were able to adapt most effectively to a world without modern, 20th century technology. And thus Mennonite beliefs about technology, in some form or another, spread widely. Technology, curiosity about technology, and scientific knowledge (and the benefits of that knowledge) are frowned upon, and in some cases even punished severely. This clamp-down on scientific exploration is enforced by the United States government - after the holocaust, the Thirtieth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution forces a rural, agriculturalist society on the nation by limiting the size of all settlements to less than 1,000 people. Without industry and the pooled resources of cities, there is no manufacturing, no science, and no technological progress. As a result, people are provincial, superstitious, and suspicious of change, and a ripe harvest for fundamentalist preachers.

Of course, human curiosity cannot be banned, despite attempts to stifle it. The Long Tomorrow is a classic post-apocalyptic coming of age tale, featuring two teenage buddies with a burning curiosity to learn about the scientific past which their elders are attempting to bury. Two cousins, Len and Esau, have heard rumors of a secret technological city, Bartorstown, that operates somewhere in defiance of society’s hostility. They discover that behind the adult facade of anti-intellectualism, there are still significant remnants of the pre-apocalyptic society. A school teacher with hidden physics textbooks, a trader with an old radio - these are perfect lures for teenage boys who think that the adults are hiding something from them. Throwing fuel on the fire is Len’s defiant grandmother, who was a little girl before the bombs fell, and still fondly remembers the material richness of her childhood society. Tears come to her eyes as she tells Len about the red dress she had as a child. There are no red dresses in Len’s society.

However fired up by their curiosity, the boys’ religious upbringing provides a powerful counterbalance. The evidence that scientific knowledge is associated with sin is too hard to ignore: science culminated in the most destructive war ever known. Len’s religious conditioning instilled in him a deep discomfort with science. However, it’s hard for him to imagine that the world of his grandmother was as purely sinful as his parents portray it, and in fact the most evil thing he sees is an anti-technology lynch mob chasing down an out-of-town trader who is accused of preaching science. Eventually, curiosity lands the boys in trouble, and they just can’t take it anymore. They set out for Bartorstown and freedom.

A plot like this could quickly get tiresome, but this is Leigh Brackett, and, as fans of The Empire Strikes Back know, she can usually pull this kind of thing off without being too preachy. This world is not black and white - Len’s father is a loving and sensitive parent, not a superstitious tyrant, and Bartorstown turns out not to be the free society that Len was hoping it would be.

A plot like this could quickly get tiresome, but this is Leigh Brackett, and, as fans of The Empire Strikes Back know, she can usually pull this kind of thing off without being too preachy. This world is not black and white - Len’s father is a loving and sensitive parent, not a superstitious tyrant, and Bartorstown turns out not to be the free society that Len was hoping it would be.Without giving away too much of the plot, I can say that Bartorstown is a big disillusionment for Len. He can’t quite overcome a deep, indoctrinated revulsion towards advanced technology when genuinely confronted with it, especially anything that has to do with nuclear energy, which is how Bartorstown is powered. Len’s first reaction is to fear that he is participating in something dangerous and sinful, something that will inevtiably be punished, although his intellect is telling him that this is the real science, the real knowledge he’s been hoping to find.

It doesn’t help Len in his struggles that Bartorstown, being constantly under threat of discovery and destruction, isn’t quite the free-thinking society Len was hoping to to be. While any ideas are free to be discussed, the residents of Bartorstown are essentially prisoners - nobody can leave without permission (the town can’t risk snitches), and in order to sustain itself, life in Bartorstown has to be extremely regimented. The whole Bartorstown community suffers, living in a mental state of siege, if not exactly a physical one. The Bartorstown native who becomes Len’s wife is his mirror image - she’s been desperate to escape her confining society about as long as Len sought to escape his.

But even more disturbing to Len is the scientific project of Bartorstown itself. While the rest of society has responded to nuclear catastrophe by going back to nature, by living in small, rural communities, the Bartorstown scientists’ solution to nuclear war is even more control over nature. They are seeking complete control over the atom to render nuclear war impossible.

Of course nobody can tell if this complete control thing is a pipe dream. The scientists in Bartorstown are unwilling to contemplate the idea that the research goal they have been pursuing is impossible. They are pinning their hopes of scientific restoration on a desperate Hail Mary, instead of trying to gradually return technology to society by smaller steps, and they are operating on the belief that society will not accept the return of science without absolute guarantees of safety. And generally, science doesn’t make many absolute guarantees.

Len and his wife eventually make their escape, but Bartorstown can’t afford to risk its existence by having them on the loose. The book ends in a cross-country pursuit, and a decision point for Len, which I won’t spoil here. It’s at this point, as Len is back in the outside world, listening to a fundamentalist, anti-science preacher firing up his congregation, that Len achieves his epiphany. As disillusioning as Bartorstown is, as hopeless the scientists’ quest for complete control appears, those opposed to science are even worse off. They also live on a desperate hope, the hope that what humans discovered once won’t ever be discovered again. The fundamentalists live on fear of science, which will leave them powerless to deal with the inevitable return of organized human curiosity. It is better to take science and recognize its imperfections.

Len and his wife eventually make their escape, but Bartorstown can’t afford to risk its existence by having them on the loose. The book ends in a cross-country pursuit, and a decision point for Len, which I won’t spoil here. It’s at this point, as Len is back in the outside world, listening to a fundamentalist, anti-science preacher firing up his congregation, that Len achieves his epiphany. As disillusioning as Bartorstown is, as hopeless the scientists’ quest for complete control appears, those opposed to science are even worse off. They also live on a desperate hope, the hope that what humans discovered once won’t ever be discovered again. The fundamentalists live on fear of science, which will leave them powerless to deal with the inevitable return of organized human curiosity. It is better to take science and recognize its imperfections.Much of this is pretty standard stuff for the post-apocalyptic genre, especially in the 1950's, but Brackett does this with more grace and subtlety than most. Inevitably these heavy themes feel a little awkward and overly earnest in places. In the end, however, The Long Tomorrow is a compelling story and one of the better post-apocalyptic books that takes on fear of technology.

Next up in our post-apocalyptic survey: John Christopher's 1956 survivalist page turner, No Blade of Grass.

Read the feed:

Comments