According to the World Health Organization, about 153 million adults need glasses and do not have them. About eight million of these people are functionally blind without glasses. As anyone who has worn glasses knows, it’s extremely hard for the others to have a normal life without them. Many everyday skills, while sometimes still possible, are made much more difficult without good vision: reading, writing, driving, mending, tailoring, and the kind of fine craft work that many people in the developing world depend on for their livelihood.

Unlike many other public health issues plaguing the developing world today, we know exactly how to help all 153 million people. All they need is a pair of glasses.

But as Oxford University’s Center for Vision in the Developing World explains, getting a pair of glasses in some countries is not as easy as you might think. While in America there is one optometrist for every 4500 people, the figure is closer to one optometrist for every 100,000 people in India and 1,000,000 in sub-Saharan Africa. Even if someone were lucky enough to find an optometrist, have their eyes tested, the facilities to make eyeglasses are also often few and far between, and traditional glasses are usually completely out of the price range of someone making on average $1 a day.

Enter Oxford University physics professor Joshua Silver with an elegant technical solution to this humanitarian problem: adaptive-focus eyeglasses. Silver has designed a single ‘universal’ pair of glasses that the wearer can adjust on their own to the appropriate lens power, eliminating the need for both eye care professionals and a costly stockpile of lenses. Since making his own early prototypes, Silver has co-founded a company, with businessman and philanthropist James Chen, called Adlens Ltd. that manufactures the adaptive eyeglasses and puts them in the hands of many non-profit groups to distribute to the developing world.

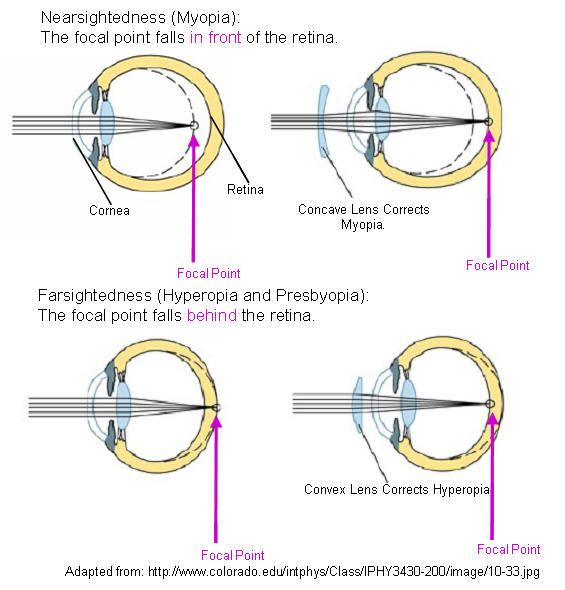

To fully appreciate Silver’s innovation and Adlens’ technology, it helps to understand how conventional glasses work. Nearsightedness (myopia) and farsightedness (hyperopia and presbyopia) are caused by the inability of our eyes to focus imag

es onto the retina. Images that don’t focus directly onto your retina will appear to you as blurry. When your eyeball is too long, or your cornea is too steep, a faraway image will be focused before it reaches the retina at the back of the eye, leaving you nearsighted. Concave corrective lenses push this focus point farther back, allowing you to see faraway images clearly. On the other hand, if your eyeball is too short, your cornea too flat, or if ageing makes the lens of your eye less flexible, images that are too close will have focal points behind your retina. Glasses with convex lenses are needed push this focal point forward enough to focus at your retina.

es onto the retina. Images that don’t focus directly onto your retina will appear to you as blurry. When your eyeball is too long, or your cornea is too steep, a faraway image will be focused before it reaches the retina at the back of the eye, leaving you nearsighted. Concave corrective lenses push this focus point farther back, allowing you to see faraway images clearly. On the other hand, if your eyeball is too short, your cornea too flat, or if ageing makes the lens of your eye less flexible, images that are too close will have focal points behind your retina. Glasses with convex lenses are needed push this focal point forward enough to focus at your retina.The stronger your near- or farsightedness, the more curvature you’ll need in your lenses to correct the focus. Because each person’s eyes have different focusing powers, each pair of glasses is made-to-order and therefore relatively expensive (needing a technician’s time, specialized lens-grinding equipment, or an expensive stock of prefabricated lenses).

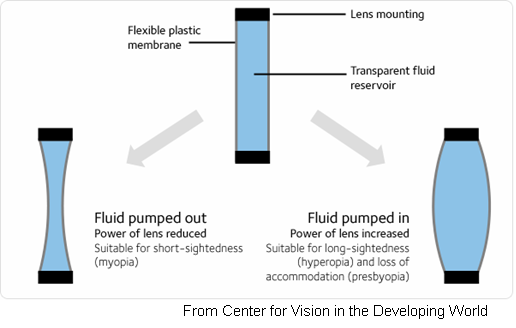

Much of these costs are made irrelevant by Joshua Silver’s new adaptive eyewear. These glasses replace traditional glass or plastic with flexible, fluid-filled cavities that have adjustable curvature. A user adjusts a dial and pumps silicon oil in or out of the lenses via a simple attached syringe system. If the user removes fluid, the lenses become concave, and can correct for nearsightedness. Adjusting the dial to add fluid,

on the other hand, can make the lens as convex as needed for focusing and can correct for farsightedness. Once the wearer has fine-tuned their lenses, they can seal off the fluid reservoir and remove the syringes. They now have a customized pair of glasses at low cost, without the need for specialized equipment or trained optometrist. This simple device and procedure can correct for 90% of the average focus problems.

on the other hand, can make the lens as convex as needed for focusing and can correct for farsightedness. Once the wearer has fine-tuned their lenses, they can seal off the fluid reservoir and remove the syringes. They now have a customized pair of glasses at low cost, without the need for specialized equipment or trained optometrist. This simple device and procedure can correct for 90% of the average focus problems.Dr. Joshua Silver describes his idea as a "tremendous glimpse of the obvious" (Guardian). Indeed, by having someone continuously change the power of the lens until they can see clearly, Silver has separated the optometrist from the process. His company can manufacture one universal pair of glasses for about $19 a pair, instead of the much costlier glass and plastic counterparts (Scientific American). Silver believes that the price can drop even further with additional mass production (their goal is $1 a pair!).

The glasses themselves may be a little bit reminiscent of Harry Potter’s, since the lenses must be round to curve effectively but they’re often not any thicker than traditional glasses.

The adaptive glasses are also durable: the fluid sacs are encased on either side with a hard, strong polycarbonate shield protecting the fluid membrane from leaks or deformations.

The adaptive glasses are also durable: the fluid sacs are encased on either side with a hard, strong polycarbonate shield protecting the fluid membrane from leaks or deformations.A number of non-profit organizations have partnered with Silver’s company, Adlens, to distribute adaptive lenses. Silver’s own non-profit organization, Adaptive Eyewear, has a pilot distribution project in Ethiopia and in Ghana the glasses are sold in over the counter pharmacies as well as distributed to remote villages by their partner in the Millennium Vision Project. The Center for Vision in the Developing World (of which Joshua Silver is director) has partnered with Global Vision 2020 to train a core of volunteer teachers, who have, in turn, fitted other adults with the glasses in a pilot project in Liberia. In addition to these non-profit organizations, 20,000 pairs have also given away by the US military in their humanitarian outreach projects. Most recently, in September 2009, the Clinton Global Initiative has funded a pilot project in Rwanda, which, if successful will result in an ambitious nationwide roll-out in 2014.

As these distribution projects develop and grow more comprehensive, Joshua Silver’s vision is making it possible for the world to see more clearly.

The following works were used as sources for this article:

Addley, E. 2008. Inventor’s 2020 vision: to help 1bn of the world’s poorest see better. The Guardian; UK News, pg 11.

Douali MG, Silver, JD. 2004. Self-optimised vision correction with adaptive spectacle lenses in developing countries. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 24.

Harmon, K. 2009. Designer Focuses on Marketing Adjustable Eyeglasses at $1 a Pair. Scientific American; Features.

Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Moriotti SP, Pokharel GP. 2008. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bulletin of the World Health Organization: 86 (1), 63.

http://www.colorado.edu/intphys/Class/IPHY3430-200/008sensory.htm

http://www.vdw.ox.ac.uk/refractiontechniques.htm