This morning I read with interest

a paper on Physics Today, titled "

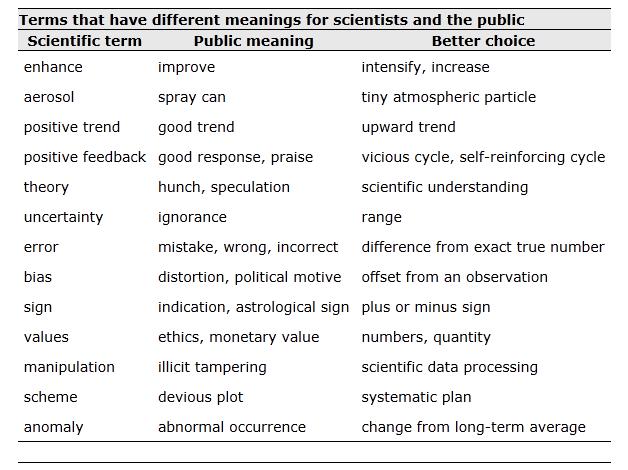

Communicating the Science of Climate Change", by R. Somerville and S. Hassol. In it, there is a table worth pondering about. Here it is:

October is passing and the neutrino saga continues to make headlines here and there, but I know that the excitement is bound to slowly dampen, as the preprint claiming superluminal speeds ages in the Arxiv without being sent to a scientific magazine.

I was happy to see today a very nice piece discussing the Opera result on allegedly superluminal motion of muon neutrinos, written by Paolo Ciafaloni, a colleague from Lecce University. The piece is in Italian, so you either know the language or need to revert to google translate or some other web resource in order to make sense of it. But the nice thing is that Paolo is caressing the idea of writing a blog of his own, and maybe in English - maybe for Science 2.0 .

The saga of the superluminal neutrinos took a dramatic turn today, with the publication of a

very simple yet definitive study by ICARUS, another neutrino experiment at the Gran Sasso Laboratories, who has looked at the neutrinos shot from CERN since 2010.

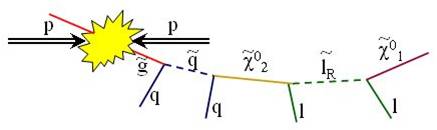

Higgs boson hunters often catch themselves dreaming of the boson having a mass high enough to give rise to the spectacular decay into two Z bosons, and then four charged leptons in the final state. At a hadron collider -let's talk of the LHC to be specific- such a signature is the only one providing events which, once properly selected, are more likely signal than background.

The situation of observing an event display being able to tell for sure what it represents, among the infinite possibilities and the intrinsic indetermination of quantum processes, is reassuring and gives a physicist a feeling of power. God did not play dice this time: those two are 100% Z bosons, and their combined mass is exactly the one of the Higgs.

I read with interest and some amusement (on the mouse joke) the

piece written here by Sascha Vongehr. I find his arguments wrong and decided to answer him in the comments thread of his post, but my answer got a bit too long and I did not want to hijack a nice discussion that was developing there; plus I found out that what I was writing could be suitable for this blog in its own right. So below I explain what I criticize about his arguments.

Living At The Polar Circle

Living At The Polar Circle Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society

Conferences Good And Bad, In A Profit-Driven Society USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research

USERN: 10 Years Of Non-Profit Action Supporting Science Education And Research Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World

Baby Steps In The Reinforcement Learning World