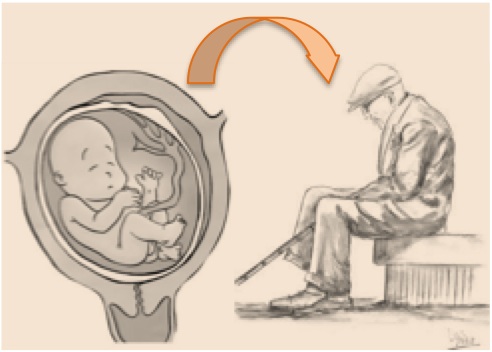

One of the most recognized markers of cellular aging is the progressive accumulation of damage in the DNA, a molecule that cannot tolerate the alteration of the genetic information coded in its bases.

For some, it is also at the root of the aging process itself.

The source of the damage to the DNA might come from the outside –solar U.V. rays will easily come to our minds- or from the inside, since our own cellular metabolism will generate a panoply of secondary metabolites –free oxygen radicals are a good example- that might alter the chemical structure of the DNA causing breaks. But there is also another major source of damage within the cell; DNA replication, the process that orchestrates the generation of an entire copy of the whole genome within the nucleus of our cells, is prone to error.

The source of the damage to the DNA might come from the outside –solar U.V. rays will easily come to our minds- or from the inside, since our own cellular metabolism will generate a panoply of secondary metabolites –free oxygen radicals are a good example- that might alter the chemical structure of the DNA causing breaks. But there is also another major source of damage within the cell; DNA replication, the process that orchestrates the generation of an entire copy of the whole genome within the nucleus of our cells, is prone to error.

The enzyme in charge of the whole operation, DNA polymerase, is human after all, and from time to time, even though a template is there and there are only four bases, it will introduce the wrong base.

Of course, the cell cannot tolerate this situation, for a cell cannot afford to alter the basic instructions that make up itself. For this reason, a lot of effort is allocated by the cell to the maintenance and repair of DNA. There are molecules in charge of surveillance, signaling the damage, and in triggering a cascade of molecular messages that will send the repair enzymes to the right place where the damage is localized to fix the problem.

Unfortunately, damage accumulates with time, either due to a decline in the efficiency of the repair system with aging or as a result of summing up those few marks that were not correctly fixed at the right time. Whatever the reason, that DNA damage accumulates in tissues with aging is a fact that researchers have been able to report when comparing young and old tissues in mice, baboons and humans. But apart from the correlative observations, there are a number of human premature aging syndromes that are caused by defects in genes that are known to be involved in the maintenance and repair of DNA.One of the best known of these diseases is Werner syndrome, caused by mutations in the Werner gene - RECQL2- a helicase, a special type of enzyme that unwinds the DNA double helix to allow access of the repair machinery to the damage.

Genetically modified mice are one of the gold standards when it comes to recognizing the function of a particular gene. Mouse strains lacking each individual component of the DNA repair system have been now generated and premature aging is one of the foremost consequences linked with the loss of DNA repair function. When researchers looked for the effects of the missing repairing function, perhaps unsurprisingly they found a huge amount of damage accumulating in the DNA. But this observation has been always done for the tissues of adult mice that somehow resembled those of aged mice at an earlier time. However, a novel mouse model of a human premature aging phenotype has allowed the researchers to propose a new and provocative theory.

Seckel syndrome is a terrible disease characterized by dwarfism, mental retardation, microcephaly and a very peculiar “bird-headed” appearance. One of the genetic defects behind the disease was identified back in 2003 to mutations in “ataxia-telangiectasia and RAD3-related” gene (ATR), certainly not a very sexy name for a gene, but suggestive of its relationship with ATM, the gene mutated in ataxia-telangiectasia, another devastating human syndrome. Both, ATR and ATM, are essential components of the DNA repair system by masterminding the operations when damage to the DNA is “sensed”.

They are protein kinases, a particular type of enzyme that mediates complex signaling within the cell by modifying other proteins through phosphorylation, initiating cascades of messages. Although not totally understood, ATM is considered the main actor when DNA is broken in both strands, while ATR is thought to operate when damage is produced during the replication process.

Previously, researches tried unsuccessfully to clearly establish the function of ATR by knocking it out in mice, but animals lacking ATR function are not viable and die soon during development. Those were the reasons that prompted Oskar Fernandez-Capetillo, a young investigator at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, to further explore ATR function and its relationship with Seckel syndrome.

Previously, researches tried unsuccessfully to clearly establish the function of ATR by knocking it out in mice, but animals lacking ATR function are not viable and die soon during development. Those were the reasons that prompted Oskar Fernandez-Capetillo, a young investigator at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, to further explore ATR function and its relationship with Seckel syndrome.The known mutations in ATR causing Seckel were described at the time as affecting the splicing of the gene. Eukaryotic genes are transcribed from DNA to mRNA, the copy that will serve as template to synthesize proteins, in the process known as transcription, but while DNA is being transcribed it is also “edited” through splicing. Some portions will be literally copied (known as exons) while others will be completely removed (known as introns). Seckel mutation impairs removal of a particular intron in the region expanding exon 8 to 10 resulting in an mRNA molecule that is very unstable and tends to be degraded. As a result, Seckel patients produce less ATR protein due to a defective copy/paste of its mRNA, compromising its repair function.

When researchers planned to reproduce this defect in the mouse, they first had to solve a problem: Human and mouse genes differ, especially in their intronic regions. Since exons are the regions of a gene actually coding for protein, they tend to be evolutionary conserved, while introns tend to diverge more rapidly. To circumvent this problem, the group led by Fernandez-Capetillo first decided to “humanize” the murine ATR gene by replacing the whole region spanning from exon 8 to 10, where the Seckel mutation resides, with the human counterpart. Replacement was done using the unaltered human portion of the gene or a mutated version, containing the known Seckel mutation (ATRs/s).

Their development was severely affected and they showed the typical “bird-headed dwarfism” appearance. By two months of age, several, but not all, the tissues in the Seckel mice showed typical signs of normal aging, such as osteoporosis and thinning of the skin. All the animals succumbed after six months to the effects of this segmental progeria (premature aging of several but not all tissues).

Further reading:

- Murga M, Bunting S, Montaña MF,Soria R, Mulero F, Cañamero M, Lee Y, McKinnon PJ, Nussenzweig A,&Fernandez-Capetillo O (2009). A mouse model of ATR-Seckel shows embryonic replicative stress and accelerated aging. Nature Genetics, 41(8), 891-8. PMID: 19620979- A short commentary by the leading author on the implications of the study:

- A review article on the link between DNA repair mechanisms and aging:

Comments