This time of year, hurricanes take over the news coverage. Hurricane season is one of those annual events nobody really looks forward to. And yet, there they come, year after year. This has spurred some people to question whether or not hurricanes can potentially be controlled. Or at least influenced.

But first, how do hurricanes form? I’ll choose the lazy option here and quote the brief but elucidating explanation given by Ross N. Hoffman:

Hurricanes grow as clusters of thunderstorms over the tropical oceans. Low latitude seas continuously provide heat and moisture to the atmosphere, producing warm, humid air above the sea surface. When this air rises, the water vapor in it condenses to form clouds and precipitation. Condensation releases heat — the solar heat it took to evaporate the water at the ocean surface. This so-called latent heat of condensation makes the air more buoyant, causing it to ascend still higher in a self-reinforcing feedback process. Eventually, the tropical depression begins to organize and strengthen, forming the familiar eye — the calm central hub around which a hurricane spins. On reaching land, the hurricane’s sustaining source of warm water is cut off, which leads to the storm’s rapid weakening.

And here’s a video explaining the process:

For more basic information about hurricanes, you can check the hurricane handbook by the NOAA.

Since hurricanes can result in great losses, both in lives lost and in material damage inflicted, dreams of controlling these weather phenomena date back to the sixties, when Project Stormfury was set up. The project attempted to slow down the development of a hurricane by seeding the first rain band outside the eyewall with silver iodide, eliciting precipitation. The results were ambiguous at best.

Newer ideas are based on the idea that relatively small changes can have large effects. So, in the case of hurricanes, small changes in a number of factors (such as ocean temperatures, wind currents and so on) might affect the hurricane’s potential path and power. By adapting forecast models, researchers have been able to backtrack a hurricane’s development for about six hours. Then, in simulations, small adjustments were made, which allow examination the effects of these small perturbations. After repeating the simulations numerous times, effective changes can be identified. The idea is to:

…find just the right stimuli — changes to the hurricane — that will yield a robust response that leads to the desired results.

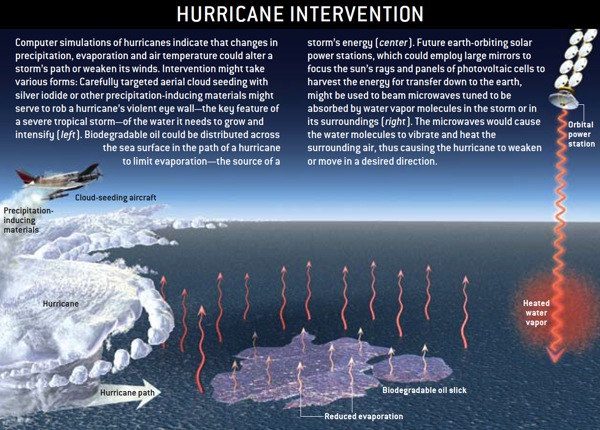

Some of the possible intervention strategies are illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: Potential hurricane intervention strategies.

(Source: Scientific American)

Two limitations of using forecast models, mentioned by the author, are:

- Even the best available models of initial hurricane conditions are incomplete. From model to reality is still a big step.

- Meteorological models are still prone to error. They are modeled in a grid, meaning that features smaller than the distance between two grid points cannot be handled correctly.

Does this make hurricane control impossible? Well, no. The models will improve, as will our understanding of the phenomena involved. At the moment, however, a lot more has to be learned about the weather in general, and hurricanes in specific, both of which are incredibly complex systems. But perhaps the costs most hurricanes incur might just warrant careful attempts in controlling them?

Reference

Hoffman, R.N. (2004). Controlling Hurricanes. Scientific American. 291(4), pp. 68 – 75.

Comments