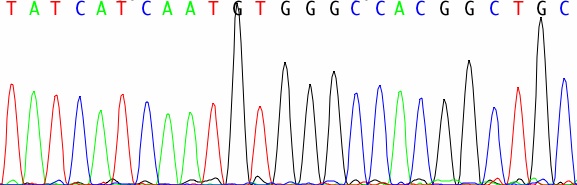

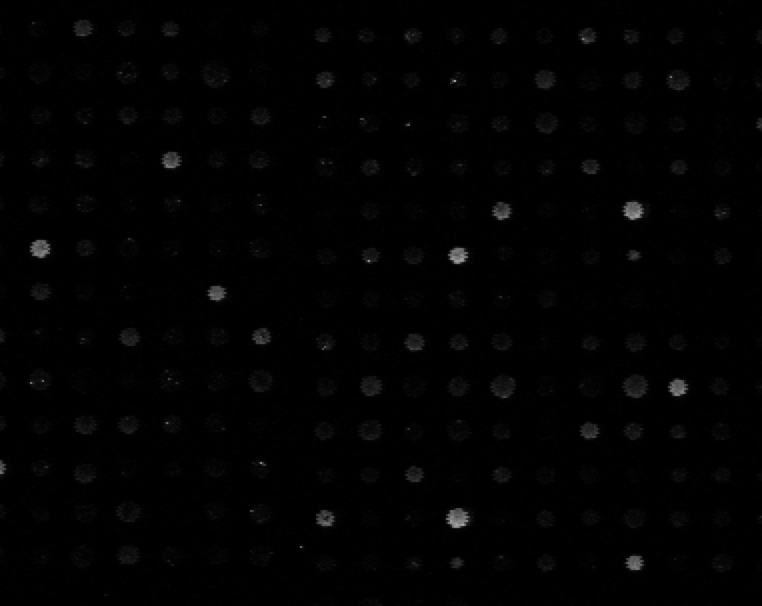

Modern sequencing machines that use this method generate a 4-color fluorescent dye readout, which you can see in the graph in the figure. Each peak of fluorescence in the graph represents one nucleotide base, and you know which base it is from the color of the dye. Next-generation sequencing, also called pyrosequencing, can't generate the nice, long sequence reads you get with Sanger sequencing, nor are the individual reads as accurate. Instead of 500 DNA bases or more, you just get about 25 bases. But the difference is that you get lots and lots of sequence reads. Instead of just one long read from just one gene (or region of the genome), you get thousands of short, error-prone reads, from hundreds or thousands of different genes or genomic regions. Why exactly is this better? The individual reads may be short and error prone, but as they add up, you get accurate coverage of your DNA sample; thus you can get accurate sequence of many regions of the genome at once. Next-generation sequencing isn't quite ready to replace Sanger sequencing of entire genomes, but in the meantime, it is poised to replace yet another major technology in genomics: microarrays. Like next-generation sequencing, microarrays can be used to examine thousands of genes in one experiment, and they are one of the bedrock technologies of genomic research. Microarrays are based on hybridization - you're basically seeing which fluorescently labeled DNA from your sample sticks (hybridizes) to spots of DNA probes on a microchip. The more fluorescent the spot, the more DNA of that particular type was in the original sample, like in this figure:

But quantifying the fluorescence of thousands of spots on a chip can be unreliable from experiment to experiment, and some DNA can hybridize to more than one spot, generating misleading results. Next-generation sequencing gets around this by generating actual sequence reads. You want to know how much of a particular RNA molecule was in your sample? Simply tally up the number of sequence reads corresponding to that RNA molecule! Instead of measuring a fluorescent spot, trying to control for all sorts of experimental variation, you're just counting sequence reads. This technique works very well for some applications, and it has recently been used to look at regulatory markings in chromatin, to find where a neural regulatory protein binds in the genome, to look at the differences between stem cells and differentiated cells, and to see how a regulatory protein behaves after being activated by an external signal. I've left out one the major selling points of this technology: it's going to be cheap. You get a lot of sequence at a fairly low cost. And this is why it may end up being the one technology that truly brings the benefit of genomics into our every-day medical care. Because next-generation sequencing is cheap and easy to automate, diagnostics based on sequencing, especially cancer diagnostics will become much more routine, and so will treatments based on such genetic profiling. It will be much easier to look at risk factors for genetic diseases. Microbial infections will be easier to characterize in detail. All of this is still a few years off, but the promise of this technology is already apparent enough to include it among the great breakthroughs of 2007. Go look at the very informative websites of 454 Life Sciences, Illumina, and Applied Biosystems, the major players in next-generation sequencing. For more on Sanger sequencing, check out Sanger's Nobel Lecture (pdf file). A recent commentary and primer on next-generation sequencing in Nature Methods (subscription required).

Comments