On of the pleasures of working there was interaction with people from other departments, and one particularly enjoyable excursion was doing pollen samples for people, so introducing me to the science of Palynology.

I was briefly looking at freshly collected pollen, but the great application of this discipline is looking at fossil pollen, particularly sediments from the last million years. The great abundance of individual pollen grains enables one to study the ebb and flow of individual plant species at one point, especially as the climate got warmer or colder, or drier and wetter, with the advance and retreat of the ice sheets.

The discipline covers not only pollen, but “spores, orbicules, dinocysts, acritarchs, chitinozoans and scolecodonts, together with particulate organic matter and kerogen”: all either organic or fossilized remains of such organic particles, including those of spores found as far back as the late Silurian.

Here are some pictures from the lab:

But how to pronounce the word? Practically everyone I know pronounces the first

syllable like ‘pal’ meaning ‘buddy’, but simplistic rules of English

pronunciation would force one to pronounce it as ‘pale’.

Which got me

thinking — could there be a science of “Palinology”, namely, how to explain

science to politicians? This so appeals to my often very infantile sense of

humour, and I can bottle it in no longer.

It has often struck me how

science is ignored in mainstream history. I have read Winston Churchill’s

History of the English Speaking Peoples, and I learned a lot from it,

including a greater appreciation of America. Including the build-up and the

aftermath, there are five chapters devoted to the American Civil War. But any

perspective on the interplay of science and history is minimal or

absent.

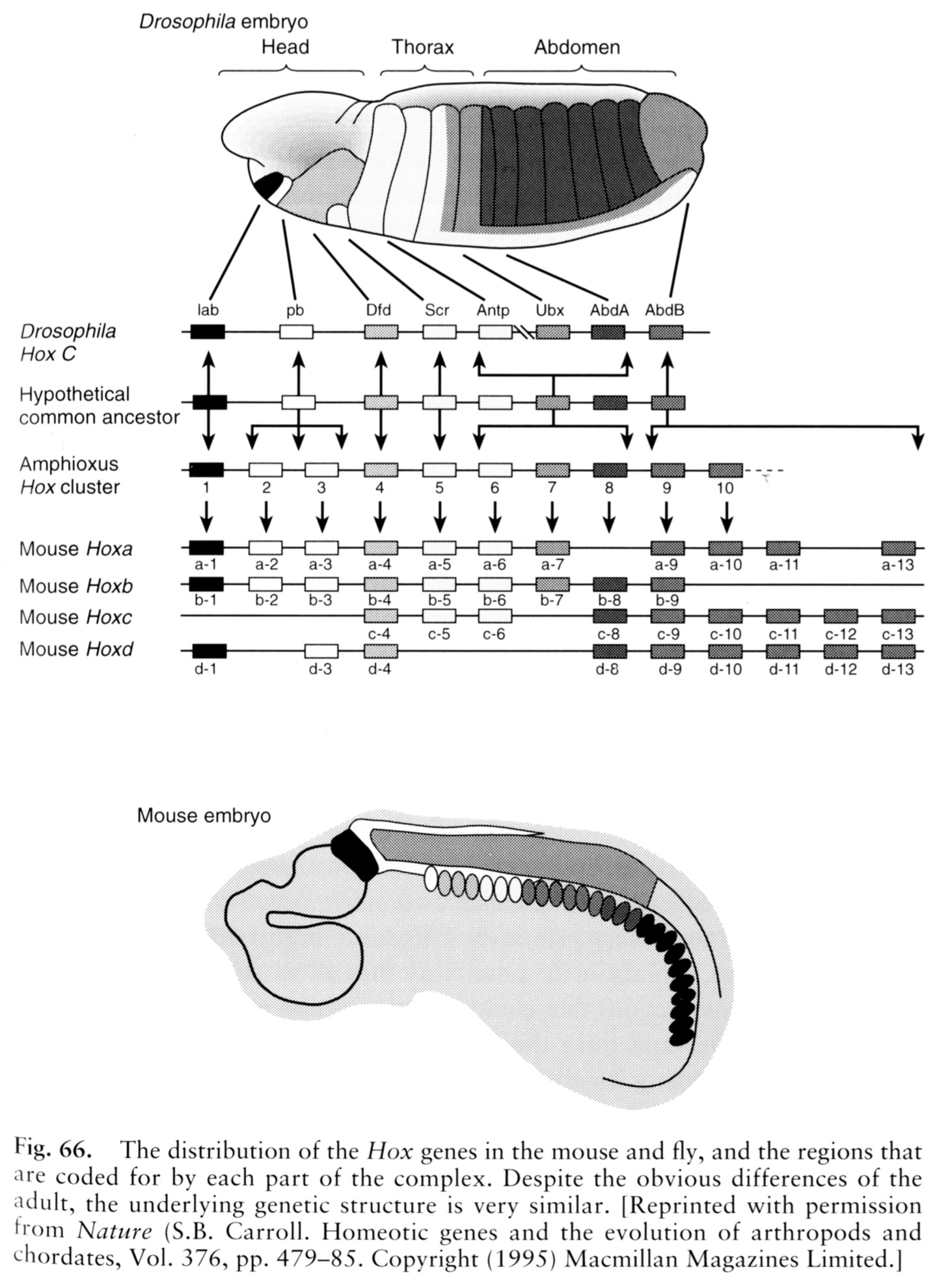

As Lord Macaulay was wont to say “every schoolboy knows” the importance of fruit flies,

particularly Drosophila melongaster, and the part they played in our development our understanding of genetics

constitutes one of the paramount episodes in science history. And today fruit

fly research is widely practiced, with implications for medicine. The picture

at the end of the article [1] shows the commonality of the Hox gene system between such widely divergent species as the fruit fly and the mouse.

And as Robert Burns says: “of mice and men ...”

So I was preparing my funny ha-ha article, in two minds as to whether to publish

it, and I got around to looking for the infamous quote. Here it is, from an

article in Live Science:

The infamous fruit fly comment came on Oct. 24 during a speech in Pittsburgh, when she explained to the crowd how "[tax] dollars go to projects that have little or nothing to do with the public good — things like fruit fly research in Paris, France. I kid you not."

Now one does wonder what the US government is doing funding research in France, but even so, to me that came as a scientific gaffe of the first magnitude. But now, look at the title of the article:

Misdirected Criticism of Palin's Fruit Fly Remark

She wasn't talking about Drosophila. She was referring to research on the olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae, either knowingly or not.

The olive fruit fly is a costly pest in the olive-growing regions of the Mediterranean and, as of about ten years ago, in California. So the USDA is spending about $211,000 to study this pest where it is endemic, in Montpellier, France — way down in the south, perhaps the most distant French city from Paris. But Palin did get the country right.

Why is this research on Palin's radar screen?

It’s worth reading the linked article to find out. The research is certainly important to California, but I will leave it to you-all to decide whether the money would have better been spent at home in the Golden State.

[1] extracted from The Crucible of Creation — The Burgess Shale and the Rise of Animals

Simon Conway Morris, Oxford University Press 1999 ISBN 978-0-19-286202-0

Comments