Sir Archibald

Henry Bodkin, KCB (1862–1957) was our British Director of Public

Prosecutions from 1920 to 1930. He particularly took a stand against the

publication of what he saw as ‘obscene’ literature.

In the 1920s he tried

to ban Ulysses by James Joyce and even threatened in 1922 to prosecute

the academic F. R. Leavis if he mentioned it in his lectures at Cambridge

University since it contained “a great deal of unmitigated filth and

obscenity”. On December 29, 1922 he banned the book, saying “As might be

supposed I have not had the time, nor may I add the inclination to read through

this book. I have, however, read pages 690 to 732.” He also stated he could

not make “head nor tail” of the book. The British ban remained until

1936.

For those unfamiliar with this expression, according to The Free

Dictionary, Neither head nor

tail means

neither beginning nor end; neither this thing nor that;

nothing distinct or definite; – a phrase used in speaking of what is indefinite

or confused; as, “they made neither head nor tail of the

matter”

However, if one wants to find a most graphic application of

this phrase, there is none finer to be found anywhere than the developmental

biology of the echinoderms, to wit the

starfish and their relatives.

Among the unsung heroes of 19th

century zoology, there must have been many microscopists who strained their eyes

studying the larvae of marine organisms. Many molluscs and crustaceans in

particular were found to go through one or more episodes of metamorphosis from

the newly hatched larva to their adult forms. But out of all of these, the

echinoderms must, I think, take the group prize.

Here, for example, are

some stages in the development of the Crown of Thorns

Starfish, that causes so much damage on coral reefs.

The

accompanying text, from Wikipedia: «By Day 1 the embryo has hatched as a

ciliated gastrula stage. By Day 2 the gut is complete and the larva is now

known as a bipinnaria (top left). It has ciliated bands along the body and uses

these to swim and filter feed on microscopic particles, particularly unicellular

green flagellates (phytoplankton). By Day 5 it is an early brachiolaria larva

(top right). The arms of the bipinnaria have further elongated, there are two

stump-like projections in the anterior (not evident in the photograph) and

structures are developing within the posterior of the larva. In the late

brachiolaria larva (Day 11)(bottom) the larval arms are elongate and there are

three distinctive arms at the anterior with small structures on their inner

surfaces. To this stage the larva has been virtually transparent, but the

posterior section is now opaque with the initial development of a starfish. The

late brachiolaria is 1-1.5 mm. It tends to sink to the bottom and test the

substrate with its brachiolar arms, including flexing the anterior body to

orient the brachiolar arms against the substrate.»

So far, so good.

Other creatures also settle down with their front ends attached. Barnacles are

crustaceans, and their life-cycle has been described thus “A barnacle has been

described as an animal that sits on its head and kicks food into its mouth with

its feet.” The larvae of many tunicates (sea squirts) also attach themselves by

adhesive spots on their front end and absorb their cerebral ganglia. As for our

starfish:

«The late brachiolaria search substrates with their arms

and, when offered a choice of substrates, tend to settle on coralline algae,

which they will subsequently feed on. In the classic pattern for echinoderms,

the bilaterally symmetrical larva is replaced by a pentamerously symmetrical

stage at metamorphosis, with the latter’s body axis bearing no relationship to

that of the larva. Thus the newly metamorphosed starfish are five-armed and are

0.4–1 mm diameter.»

This is a somewhat limited account of the

process. Referring

this time to Living Invertebrates:

«The final stages of metamorphosis are completed rather rapidly. A new mouth breaks through on the larval left side through the middle of the ring canal, while a new anus opens on the larval right side, thus producing an adult axis at right angles to the larval axis. The 5 radial canals grow out and develop tube feet, the body takes on the adult shape, and the young sea star crawls away to a new life.»

The starfish, however, form

but one of the five extant groups of echinoderms. Here are all five, presented

in a cladogram from University of California, Berkeley:

At the top we see

the Crinoidea, or sea lilies. These are the Pelmatozoa, or stalked

animals, even though the feather stars during their development leave their

stalk behind and wander off freely.

The other four classes form the

Eleutherozoa, or free-living animals. Working out the relationship

between the four classes seemed well-nigh impossible, until molecular biology

came along and allowed them to be grouped in two sets of two, as in the

cladogram. Easy enough, you may think, until their larval development is

compared.

Here is part of a diagram from Echinoderms by David

Nichols (1962). It shows the larval development of the four classes, but I have

picked out the starfish or Asteroidea (left) and the sea cucumbers or

Holothuroidea (right).

At e in the left-hand column, we see the star

rudiment with the developing starfish mouth breaking off, and leaving behind the

larval front end with its larval mouth (or else the larval body may be

absorbed.) However, with the sea cucumber, there is a bit or torsion of the

internal organs, but it keeps its larval mouth, even though the internal vessels

of the little animal are growing into the five-fold symmetrical pattern in a

manner quite similar to the starfish. But most of the adult sea cucumber’s body

is developed from larval tissue.

To make matters worse, the other two

classes, namely brittle stars, develop via pluteus larvae, (pluteus meaning

“easel”) which have extra arms compared to the other two. Here is an example of

an echinopluteus larva of a sea

urchin.

Here is a table summarizing these differences:

|

Class |

Which mouth? |

Pluteus? |

|

Starfish |

New mouth |

|

|

Brittle Stars |

Larval mouth |

Pluteus |

|

Sea Urchins |

New mouth |

Pluteus |

|

Sea Cucumbers |

Larval mouth |

|

Seeing how these features

fit in with the molecular picture shows that trying to work out a consistent

evolutionary plan from the larval morphological development could lead nowhere,

almost as if it had been designed with the specific purpose of driving

evolutionary developmental biologists mad.

From Bilateral to Pentradial

Many “primitive” creatures

like cnidarians (jellyfish, sea anemones, etc.) are radial, while a majority

“higher” creatures are bilateral, with a left and right side, a top and a

bottom, and a front-to-rear axis. Sometimes this symmetry is broken, as in

snails with their spiral shells, but in development they start out bilateral,

and twist, but some organs on one side may not develop.

The development

of larval forms of echinoderms (starfishes, sea urchins, etc) starts out

bilateral, and the radial form develops by metamorphosis. In the later

19th century there developed the theory of

recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological

parallelism— often expressed in Ernst Haeckel’s phrase as “ontogeny

recapitulates phylogeny. This now largely discredited biological hypothesis

states that in developing from embryo to adult, animals go through stages

resembling or representing successive stages in the evolution of their remote

ancestors. «Embryos do reflect the course of evolution, but that course is far

more intricate and quirky than Haeckel claimed. Different parts of the same

embryo can even evolve in different directions» (University

of California Museum of Paleontology).

Even so, in echinoderms

the course of larval development is overwhelmingly strong that the remote

ancestor of the echinoderms was bilateral.

The early Cambrian has yielded

many strangely shaped echinoderms, which look as if they were half-way between a

bilateral and a radial state. Now, within the last year or so, the two ends of

the sequence between bilateral and pentaradial have been discovered in the

fossil record.

The first thing that the Natural History Museum in London

brings to mind is most probably dinosaurs, though as I walked round the gallery

with a Mesozoic scene I was looking rather at the vegetation. But for years

there has been a very active group, headed by Dr Andrew Smith, working on

echinoderm fossils from all over the world, who have discovered

two new creatures at each end of the development.

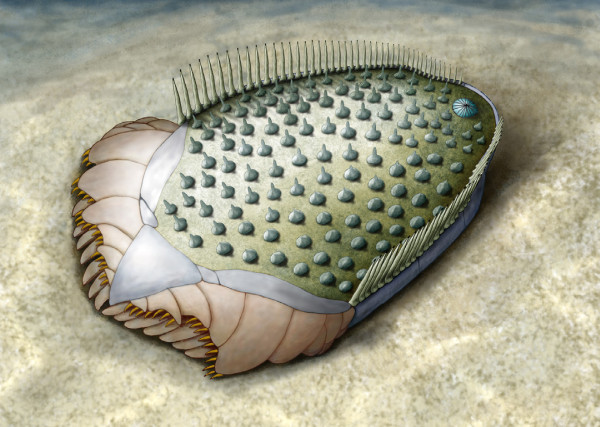

First, from Spain,

comes this bilateral creature Ctenoimbricata spinosa, published in 2012

[1]. A bilateral echinoderm Courtessolea moncereti was known since 1999

from a rather damaged specimen, but a more complete one has also turned up. But

Ctenoimbricata also seems to represent a more primitive version of this

body plan.

Secondly, this year we have the (so far) earliest

known pentaradial echinoderm, Helicocystis moroccoensis (from guess

where!) [2]

Here is part of a figure from [2] showing a progression

from the bilateral to the pentaradial form

Furthermore, the new

pentaradial specimen seems to sit nicely as an ancestral form. So, what shall

we call this creature? Let us give it fine sounding German

name:

der

Urfünfzähligsternförmigstachelhäuter

(meaning the original

five-numbered star-shaped prickly-skin!)

But whatever you call it, I have

complete sympathy for anyone who says they can’t make head nor tail of

starfish!

====================================================================

1] Title: Plated Cambrian Bilaterians Reveal the Earliest Stages of

Echinoderm Evolution

Author(s): Zamora, Samuel; Rahman, Imran A.; Smith,

Andrew B.

Source: PLOS ONE Volume: 7 Issue: 6 Article Number: e38296

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038296 Published: JUN 6 2012

[2] Smith

AB, Zamora S. 2013

Cambrian spiral-plated echinoderms from Gondwana reveal

the earliest pentaradial body plan. Proc R Soc B 280:

20131197.

Comments