Fareed Zakaria argued on CNN that the U.S. economy is struggling in part because President Obama gutted federal research and development funding, and that American students have fallen behind in science education.

While it's true that Democrats are more likely to cut funding for science, President Clinton did the same thing after the science gold rush of the Reagan and Bush administrations as Obama did after the 43rd President, George W. Bush, Zakaria was interested in our comment noting that American students haven't fallen behind at all. We simply don't teach to standardized tests the way Asian countries do. Yet the American critical thinking approach results in the world's highest adult science literacy, science output, and Nobel prizes.

CNN invited Dr. Alex Berezow and I to write on the topic and that is below.

Has America really underinvested in science education?

On Global Public Square last month, Fareed Zakaria made the case that the U.S. economy is struggling in part due to poor investment in science. He based this conclusion on two claims: First, that federal research and development (R&D) investment has declined over the past several years and, second, that American students have fallen behind in science education.

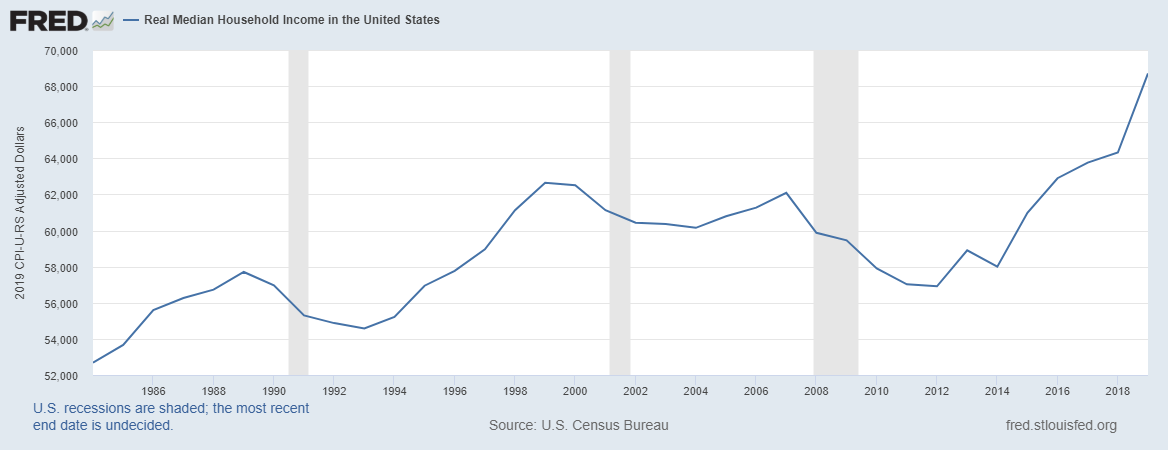

The first claim, while true, only tells part of the story. As we discuss in the upcoming Science Left Behind, American R&D investment has been relatively consistent for the past 30 years, never dropping below 2.3 percent of GDP. Though the federal portion of U.S. R&D investment has fallen during this period, the private sector has actually picked up the slack. Indeed, the most recent estimate for 2012 shows that the U.S. will spend approximately 2.85 percent of its GDP on R&D.

How does this compare with other countries? Japan (3.48 percent), Germany (2.87 percent) and South Korea (3.45 percent) outspent the United States in R&D when it is measured as a percentage of GDP. But these numbers are misleading because they fail to recognize the proper context – that is, the sheer enormity of the U.S. economy. Though the U.S. “merely” spends 2.85 percent of its GDP on R&D, in absolute terms, that’s $436 billion – more than all of Europe combined. In fact, if all of the world’s R&D money was placed in a giant pot, nearly one out of every three dollars would come from the U.S.

Zakaria invokes international standardized test scores to support his second claim that young American students are falling behind. However, American students haven’t really fallen behind – they never did well on international standardized tests in the first place.

In 1964, U.S. students participated in the First International Math Study. How did they do? Not well. They placed 11th out of 12. In 2009, American students had math scores placing them 25th out of 34 countries in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) exam. This sent education lobbyists on a quest for more funding, even though the U.S. already spends $91,700 per pupil from kindergarten through 12th grade (behind only Switzerland, which still placed only 8th in math).

Despite poor performance on standardized test scores, the United States has led the world in Nobel Prizes and is widely recognized as the indisputable leader in higher education and scientific output. American education teaches kids how to think, not how to take standardized tests. And importantly, smart immigrants keep flocking to the United States, largely because of education.

Zakaria’s concern is understandable because everybody wants a more educated society, but there’s little evidence that creating more scientists will actually help get the economy back on track. Careers in academia are extremely difficult to find, as any post-doctoral researcher will testify. For instance, only 14 percent of biology PhD’s obtain an academic position within five years. For engineering, it’s 15 percent. Even in the field with the most success, the social sciences, less than half of PhD’s find an academic job within five years.

And the most depressing statistic: More than 5,000 janitors in the U.S. have PhD’s.

Much of the existing evidence instead indicates that America has too many highly educated people, and simply not enough jobs for them to fill. Because of this, The Economist recently concluded that earning a PhD may often be a waste of time.

Obviously the solution isn’t less education. But education itself is not a magic bullet, and we simply can’t turn every person into a scientist. Science is difficult and jobs are limited. Perhaps a better strategy would be to modify America’s immigration policy. We should continue to open our doors to foreign students who want to learn at the best schools in the world. But we should stop making student visas easy to get while making work visas after they are educated difficult to acquire. That legacy of protectionism results in the world’s best and brightest being forced to return home to compete against us.

Making America a more welcoming country for motivated immigrants is what made us great – and will continue to do so in the future.

Comments