A new patient sits across from me in the exam room, confused and frustrated at her lack of progress trying to lose weight for the last 30 years. 200 pounds too heavy, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, hypertension, sleep apnea, infertility and osteoarthritis. She needs knee replacements, but is too heavy to be approved for the surgery. She asks me, the “weight loss doctor,” what my plan is for her. And I think:

“What does it take to get referred to a bariatric surgeon in this town?”

I’ve been interested in obesity since I began medical practice 14 years ago, but I have to admit that I believed it to be a lifestyle and behavioral disorder until about 6 years ago, when I learned about bariatric surgery at an American Diabetes Association meeting. I was lucky enough to be in a session hosted by some of the pioneering surgeons and researchers in the field. They described their initial reaction to the first patient with type 2 diabetes who underwent gastric bypass surgery.

They had presumed that as the patient lost weight, his metabolism would improve and that they would eventually be able to reduce or even eliminate the patient’s insulin. What happened instead is that the patient’s blood sugar normalized and insulin became unnecessary while he was still in the hospital.

In a matter of days, the “insulin resistance” that was thought to drive type 2 diabetes, as if by magic, resolved. The patient’s natural ability to sense incoming nutrients, secrete insulin to manage the nutrients, and the body’s ability to accept the action of insulin, all normalized within the course of a week. The surgeons were, to say the least, a bit surprised.

Surprised and excited. So they performed bariatric surgery on a second type 2 diabetic, then a series of diabetics and observed, over and over again, that the surgery seemed to reverse the disease process in 80-90% of their patients. The patients came in on insulin, left a few days later off of it, perhaps never needing it again. Long before any weight loss occurred.

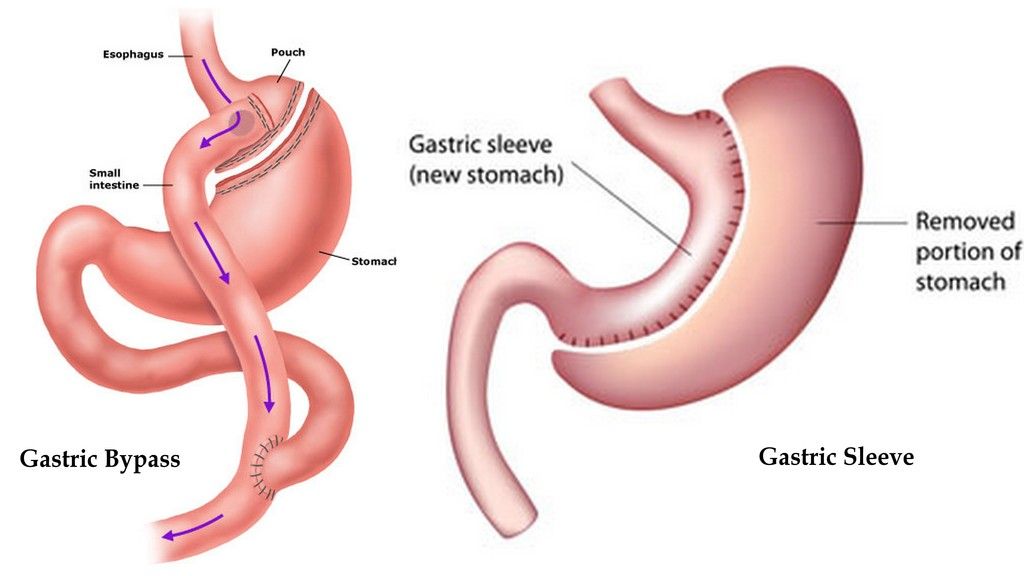

Dr. Francesco Rubino, who regaled the audience at the ADA with his tales of rat bypass surgery, showed that type 2 diabetes seems to depend on specific food-gut interactions. He explained that a bypass works by separating a large portion of the stomach and rerouting the intestine so that food goes from a smaller stomach directly into the end of the small intestine. This “bypasses” most of the small intestine, where a lot of our digestion occurs. It helps with weight loss for obvious reasons: your stomach is tiny, so you feel full quickly, and if you eat, it’s hard to absorb the nutrients, since the small intestine has been bypassed.

He performed bypass on rats bred to be obese and diabetic and showed that, just as in humans, type 2 diabetes went into remission with surgery. He then reversed the gastric bypass and showed that the diabetes came back. He postulated that the bypass, by depriving the small intestine of nutrients, was causing a change in the food-gut-hormone pathways that regulate how we deal with food energy.

To test this, he stuck tubes down the rats’ throats through the stomach, past the first part of the intestine and found that it worked just like bypass: diabetes went away, without the big surgery. He pulled the tube out and the diabetes came back. He wanted to make sure that it wasn’t just the tube doing something, so he put holes in the tube, so that food could leak out. The diabetes came back. Back and forth, over and over again, in these (he called them) heroic rats, with diabetes getting switched on and off, depending upon whether nutrients came in contact with the small intestine.

Today, these results have been reproduced everywhere that bariatric surgery is systematically studied. Gastric bypass as a "cure" for diabetes is commonplace (though many doctors seem not to know it). But the results seem to vary by the method of surgery. If one compares gastric bypass to gastric banding (in which the stomach is constricted by the band into a small pouch similar to bypass, but is otherwise left intact) the banding patients do not have nearly half the luck regarding diabetes resolution, and it seems dependent on weight loss. This would seem to make it obvious that Dr. Rubino and others were right when they considered diabetes to be caused by the interaction of nutrients with the duodenum (first part of the intestine).

However, gastric “sleeve” bypass, which cuts away a lot of tissue, leaving only a sleeve shaped stomach to receive food, but without bypassing the duodenum, does almost as well as the traditional “Roux-en-Y” bypass. Logically, the sleeve bypass, which leaves one hooked up end to end without disruption, should do no better than banding if the cause of diabetes is simply food touching the duodenum.

In a 2011 article in the Journal of Physiology, Erik Hansen and colleagues built upon the work of these pioneering surgeons by looking at the body’s hormonal response to bypass surgery. Their goal was to test whether the food actually touching the duodenum was the direct cause of diabetes remission in bypass patients. They came up with a clever way to examine this idea. They checked patients before and after bypass with regard to blood sugar, insulin and other related hormones. They checked how the patients’ bodies reacted to food delivered to different parts of the digestive system by inserting a tube into the stomach, connected through the skin to the outside world, at the time of surgery.

This way, the study subjects could eat food by mouth, have it travel down the bypass route straight to the jejunum (missing the duodenum), or, have food put into the gastric tube connected to the stomach left after surgery (note in the diagram above, that the stomach remains in the body after Roux En Y bypass). This second way of feeding would put the food through the old route of stomach, then duodenum, etc. So the subjects could act as their own controls in an experiment that compared a human reaction to the same food delivered in three ways: before surgery with normal anatomy, after surgery using bypassed anatomy and after surgery using a tube that would still have food pass through the entire small intestine (which is not removed during bypass, as it is needed to transport bile from the liver and digestive enzymes from the pancreas). What did they find?

For those of us who thought Dr. Rubino's rat experiments explained type 2 diabetes, as I did, the results were surprising. The patients all had improvements in blood sugar, insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity and other hormone response to food. But the route of food administered to the subjects made no difference. Whether food came in the stomach and touched the duodenum, or was eaten to bypass the duodenum, the patients appeared to be sensitive to insulin again. This argues that something else happens during or shortly after bariatric surgery to cause the change in insulin sensitivity. The surgery itself changed the way the subjects responded to food later, regardless of whether or not the food touched the duodenum.

In 2012, two papers in the New England Journal of Medicine made headlines for reporting diabetes remission rates between 37% and 95% with bariatric surgery (Schauer and colleagues, Mingrone and colleagues, both on 3/29/12). Previous accounts of diabetes remission after bypass were primarily observational. That is, they simply reported the outcomes for the patients that they operated on. They were without randomization and comparison groups. Based on those earlier studies, the consensus has been that type 2 diabetes is reversible by surgery with the following caveats:

The shorter the duration of diabetes, the better

The milder the case, the better

Patients on insulin are harder to “cure”

The more drastic the surgery, the better

Roux –en-Y is best for diabetes, then gastric sleeve, then gastric banding.

The New England Journal studies improved upon our understanding of these questions in three ways. First, by comparing the surgery patients to conventional medical treatment groups, both studies were able to quantify the degree of improvement expected by surgery, which previously was simply assumed. Second, by taking patients with greater duration and worse disease, the Schauer study gave surgeons a more realistic view of how patients in a real bariatric practice can expect to fare. Third, the Mingrone study confirmed that bilio-pancreatic diversion is better than traditional Roux-en-Y bypass in a study with a control group.

The Schauer study was conservative in its conclusions, I think to a fault. By reporting the percentage of patients reaching a target hemoglobin A1C (a measure of average blood sugar over months) of less than 6% as the definition of remission of diabetes, they downplay the fact that the vast majority of surgery patients had tremendous improvement, stopped nearly all medications and came very close to complete remission in one year. The 37% and 42% remission reported tends to understate that improvement. The tables included in the article make clear that one could state with confidence that surgery will drastically improve diabetes, probably make all medicines unnecessary and nearly guarantee a major change in the risk of long term complications such as heart disease and renal failure.

The trouble with both of these studies is that the comparison group was “conventional medical therapy” (despite the fact that Schauer and colleagues termed it “intensive”). What does conventional medical therapy mean? This means piling one medicine on top of another to reach blood sugar targets and to give half-hearted advice about lifestyle changes.

What do I mean by “half-hearted?” How about, “encouraged to participate in the Weight Watchers program?” To me, that’s about as half-hearted as it gets. The diet advice was perhaps just slightly worse than what you might get from your neighbor…In my clinical experience, very few candidates for bariatric surgery have not tried Weight Watchers or other commercial programs, repeatedly.

So what would be a good comparison group?

In “Reversal of type 2 diabetes,” published in Diabetologia in 2011, E.L. Lim and colleagues tested whether eating like a bariatric surgery patient would have the same effect as actually having the surgery. In short: they starved their patients without first operating. This was set up to test what exactly needs to happen for diabetes to disappear. Is it the nerves or hormonal changes that occur with the operation? Is it altering the food/gut interaction? Could it simply be that you never eat much again?

They took 11 volunteers (people don’t line up for starvation studies) with type 2 diabetes and fed them a diet of 600 calories per day for eight weeks. They found that after one week of dramatically reduced calorie intake, blood glucose levels entirely normalized in these diabetic patients. They also showed over the eight weeks that fatty liver and fatty pancreas (one of the keys to type 2 pathology) were entirely resolved. The patients were secreting a normal amount of insulin and their insulin resistance resolved as well. It was as if the patients had had surgery.

Keep in mind that this was one hundred year old news when it came out. The original treatment of diabetes, both types, was starvation and/or complete carbohydrate restriction.

Is this a fair comparison? Starvation vs. bariatric surgery?

It’s a better comparison than “conventional medical therapy.” I’ve worked in the bariatric surgeon’s office and compared notes with the surgery dietitian. We’ve shared pictures of the meals eaten by successful surgery patients and successful weight loss patients in my clinic. Believe me, successful bariatric surgery patients are eating very little, perhaps not much more than the starvation patients in the Lim study. When surgery patients, over time, increase calories, one, five, ten years out, the weight begins to creep back. When surgery patients are in their first year of recovery and the weight is coming off effortlessly, they don’t seem to regain a normal metabolism so much as they seem to be able to very successfully follow a crazy rigid diet without any hunger. It makes them, to my mind, wired like a naturally skinny person: easily full, kind of nauseous with overeating and prone to eat more nutritive foods. They can even resemble anorexia nervosa patients.

Perhaps there is no mystery as to why the surgeries, such as gastric sleeve, that leave the anatomy intact, are still quite useful for diabetes. Because of the surgery, food is drastically reduced. In addition, to avoid protein starvation, post-surgery patients are counseled (almost hounded) by the team's dietitians to meet protein goals before all else. It may actually be one of the highest protein and lowest carb diet programs out there.

With regard to long term follow up, surgery remains the most effective treatment we have for diabetes. However, medical physicians are generally reluctant to recommend this drastic approach to a disease that can be well managed with medications. In addition, every physician has patients or knows of cases who have had the surgery and found only temporary relief of weight and diabetes. These exceptions to the rule tend to make an impression, as they confirm a natural bias against unnecessary surgery. This is made worse by the track record of early surgical programs which took the heaviest, sickest patients for bypass first and, not surprisingly, had poor outcomes, including high mortality rates.

Since best practices and quality standards became widespread between 2000-2010, the mortality and other complications from gastric bypass have plummeted and the safety concerns are inaccurate. An analysis from Dimick and colleagues published in JAMA in 2013 showed the mortality risk from gastric bypass to be equivalent to that of removing a gallbladder. To my way of thinking, our reluctance to consider gastric bypass in our patients may reflect an ongoing fat bias and an old fashioned understanding of the disease: that it is caused by gluttony and can be cured by willpower. Once we drop this way of thinking, we should look for the most effective treatment available for our patients.

With the "sleeve" gastric bypass, there is nothing particularly "drastic" about the procedure. The operation takes less than one hour, it is performed through scope incisions and blood loss is generally negligible. Yet physicians remain skeptical, pointing to the few exceptions they've seen. When I discuss this with patients, I point out that we don't stop sending people for knee replacement because we know of one or two patients who continued to experience pain, or needed re-operation, or even had blood clots and died. We consider these unfortunate outcomes as the rare, but possible, risks of any major surgery and believe that the benefits outweigh the risks. With regard to bariatric surgery, the irony is that we do continue to refer those same patients for knee replacements and other procedures with worse risk profiles than gastric bypass.

We are only reluctant to send them for the one procedure that might lower their long term risks for bad outcomes from any procedure.

The early operations didn't kill patients because the surgery was risky. It was risky to operate on those patients for any reason. The improvement in mortality that's occurred over the last twenty years reflects, in part, surgeons selecting safer patients to operate on, rather than improvement in the surgical techniques.

In addition to a primary physician's lack of updated knowledge regarding the risks of bariatric surgery, there is (again, unfounded) belief that the improvement in weight and diabetes with bariatric surgery is temporary. After five or ten years, some physicians believe, the diabetes comes right back. To assess this question, David Arterburn and colleagues followed over 4,000 gastric bypass patients for 10 years to look at the longer term results. Their study, published in Obesity Surgery in 2013, found 68% of previously diabetic bypass patients to be diabetes-free at 5 years and 40% to remain so at 10 years. To my way of thinking, this is a report of one of the major triumphs in modern medicine. While surgery can't be thought of as a universal cure for diabetes, after surgery most medications, most especially injections with insulin, will be unnecessary, and the disease will almost certainly become easily managed, with minimal medication.

Lest we get too enthusiastic about a surgical cure, there are some important caveats to consider: First, while the mortality rate of bypass surgery has been dramatically reduced, there are still post-operative risks that come with sudden weight loss, starvation type eating, and poor absorption of nutrients. After surgery, deficiencies in iron, albumin, calcium and vitamin D are commonplace (as reported in a recent Lancet review, May, 2015, Ikramuddin and colleagues). Bariatric surgery patients require supplementation and lifelong monitoring of vitamin levels. When surgery is performed on individuals unable or unwilling to be vigilant about protein intake, this deficiency will cause muscle wasting and hair loss. In my practice, I was usually able to spot patients who had had previous bariatric surgery by the distinct lack of normal muscle contour around the shoulders. Additionally, surgery patients never get to enjoy food in the same way. The surgery forces tiny, very frequent feedings, that need to be followed without the normal call and response of hunger and satiety. The general recommendation is to never eat and drink at the same sitting, as the liquid fills the smaller stomach and does not allow enough food to be consumed. Alcohol is considered off limits because fast absorption makes its effects felt much more quickly and severely and addictions are more common after the surgery. It is safe to say that you would not wish this surgery on someone if they had other choices.

Obesity and diabetes are not the same. When it comes to type 2 diabetes, I think it is fair to say that patients have some good choices. Starting metformin early, adding other oral medications when and if glucose is not controlled, utilizing newer injectable medications and insulin when required provide a host of opportunities to keep type 2 diabetes from causing serious harm. Surgery should continue to be reserved for when these measures fail. But those measures do fail, quite often. Either through lack of ability on the patient's part to stick to monitoring and strict medication adherence, or due to the severity of the disease, many type 2 diabetic patients go on to have amputations, heart attacks and kidney failure. Earlier consideration of surgery would prevent many of those secondary consequences.

At meetings for bariatric societies, it is commonly stated that less than one percent of individuals who could qualify for gastric bypass surgery are having the procedure done. "Qualify"would mean, in this case, that a person's BMI is over 40 (generally 100 pounds overweight) or have a BMI of 35 with diabetes. If a person fits those criteria, society guidelines and insurance are in favor of surgery. If we take the one percent number at face value and consider next steps, where does that lead?

If we were to recognize that bariatric surgery is vastly under-utilized, mis-understood and much more effective at treating obesity and type 2 DM than anything else, we might consider trying to put a dent in the 99% of the population that's not having surgery. To make any real progress, we could advocate for developing ten times as many bariatric surgery centers as we currently have. In Iowa, where I live, this would mean that, instead of 5 centers, we would have 50...in more populous states the numbers would be proportionate, so that in big cities you would see 40-50 bariatric surgery centers competing to re-route your gut.

Even if this were feasible, we would then be treating only 10% of those who qualify for surgery with one of the versions of gastric bypass. 90% of the risk for kidney failure, heart attacks and amputation would remain. It goes without saying that we can't scale up another order of magnitude to 400-500 surgery centers competing in big cities. We will simply have to do something with the food to get in front of this problem.

Bariatric surgery is very effective, but also immensely impractical. For me, it is interesting mostly because of what it tells us about obesity mechanisms and how diabetes works. I don't think we are ever going to live in a world where bariatric surgery is commonplace. I think it's much more likely that the solution to type 2 DM and obesity will occur elsewhere.

Comments