That would be a strange beginning, wouldn't it?

We know, intuitively, that obesity and the metabolic diseases are primarily food-related and any weight loss patient would first and foremost expect that it would be diet that needs to be addressed in that first meeting with the obesity specialist. But, like anyone inexperienced in treating obesity, I began with the assumption that to help people lose weight, you would need to address both diet and exercise. When my first clinic opened in 2011, I asked the hospital for three staff members: a dietitian, a health coach and a fitness trainer. We were slow to find the right trainer and a couple months after opening, I had them cancel the job posting.

In the first several weeks, I discovered that weight loss, for the very heavy patients I was treating at least (I was the medical doctor in a bariatric surgery office, so all the patients were at least 100 pounds over "ideal" weight) had little to do with activity. Successful patients appeared to be those who made big changes in diet. I found that my patients who simultaneously took it upon themselves to exercise did no better than those that didn't. In fact, they seemed to be having a tougher time, perhaps by wasting too much effort on the wrong part of the energy balance equation.

Then, there were all the issues with injuries. Not surprisingly, when one is a very heavy middle aged person who suddenly begins an aggressive exercise program, injuries are common. One afternoon, I got frustrated and left a somewhat cryptic message for Lance Farrell, the owner of a local chain of martial arts-based fitness centers:

"Please stop breaking my patients' feet."

Lance is a positive, confident guy, so instead of getting defensive, he got in touch with our office to set up a meeting to discuss what was going on. I explained that I had met three patients in three months who had recently dropped out of his fitness challenge course because rising up on one foot to perform martial arts kicks had caused stress fractures in the metatarsal bones of their feet. "Like a dancer's fracture?" Lance asked and I knew I had an intelligent partner.

Working together over the following few months, we designed an alternative program to his other "boot camp" style competition. This involved screening heavier and sicker individuals more carefully and offering a run-in program to get them ready for the full-on daily intensity of the "extreme bodyshaping" course that the gyms are famous for. It worked well, prevented injuries, provided an outreach to people who otherwise would eschew work-out programs and continues to run in the Des Moines facilities. For Lance, it turned out perfectly. For me, the entire episode made me question how important exercise really should be for people who are not naturally athletic.

The idea that we should exercise to help with weight loss is logical enough. Weight is the cumulative result of a daily energy balance between what we put in and what we use. Since exercise uses energy, it would seem reasonable to increase the "out" side of the equation while simultaneously reducing what goes "in."

But how big of an impact can exercise have?

Recall the breakdown of energy expenditure:

E = DIT + PA + RMR + NEAT

Where "E" has its four components: diet induced thermogenesis (DIT) which is the amount of energy we use digesting our food, plus physical activity (PA) like running and working out, resting metabolic rate (RMR, which is the brain, heart, liver and kidneys just keeping everything going) and "non-exercise activity thermogenesis," which we call NEAT (including fidgeting and all other movements not measurable as PA).

These factors vary between individuals, but the average percentage of calories burned by each of the factors is generally agreed to be roughly:

RMR: 60-65%

DIT: 5-10%

PA: 20%

NEAT: 10%

(Extrapolated from Thomas, 2009)

These factors vary depending on age, weight, activity level, etc. But no matter what, the vast majority of our energy is spent simply keeping the organs functioning and digesting our food. The brain alone accounts for 18% of energy burned daily, or, more than you can spend in deliberate exercise. At first glance, one might be tempted to think that increasing "PA" by exercising, would, over time, make the difference between lean and obese. But one needs to consider that physical activity includes all of your activity while awake, 16 hours or more of movement, not just your exercise. This includes getting ready for work, dressing, showering, walking to and fro, etc. From a strictly mathematical standpoint, even if you chose to exercise an hour a day, every day (and very few of us can keep up a commitment like that) you would be acting on only 1/16th of of 20% of your metabolism. Everyone who exercises an hour a day, spends 23 hours per day not exercising. There is simply no way around this fact.

This is born out in studies which assess the effect of formal exercise on weight. In a 2005 review in the International Journal of Obesity, Curioni and Lorenco examined the results of studies which compared diet alone with a diet + exercise prescription, (choosing only studies which accurately measured both parameters). They found, when synthesizing the results of the six trials that met their rigid criteria for quality, that exercise led to a (statistically insignificant) greater weight lost of 6.5 pounds in the short term and a 4 pound greater (again insignificant statistically) weight loss at one year. This was on top of a one year average weight loss of 10 pounds across all studies.

In a more recent review published in the American Journal of Medicine (Thorogood, 2011), researchers looked at the impact of aerobic exercise without dietary changes, on 3 month and 12 month outcomes. Fourteen randomized controlled trials were analyzed to show that aerobic exercise of at least 120 minutes per week produced very modest weight losses of 2-4 pounds at 3 months which were maintained at the end of a year. There were also small improvements in waist circumference (one inch) and blood pressure (2 mmHg).

As I've pointed out previously regarding weight loss results, we could delve deeper into these studies, try to assess whether resistance is better than aerobic exercise, or interval training beats them both, but what's the point? The details don't matter much when the big picture analysis gives results of 2-6 pounds! Obesity is a complex medical disorder with identifiable hormonal, metabolic, neurologic derangements in the context of large amounts of weight gain. If exercising consistently for a year is only going to improve weight by single digits, we need not impose this extra burden on our patients, or ourselves.

Many physicians argue that the advice to increase exercise is not really about pounds on the scale, but measurable risks for disease. Exercise improves cholesterol, blood pressure and inflammation, even without much weight loss. Leaving aside for the moment the fact that patients themselves do, in fact, measure success in terms of pounds, not mmHg blood pressure or mg/dL cholesterol, what amount of exercise would be required to change medical risk?

This question was addressed by Cris Slentz and colleagues in "Exercise, Abdominal Obesity and Metabolic Risk: Evidence for a Dose Response." In this 2009 paper, the researchers looked at how much and how hard we need exercise to improve our risk for diabetes and heart disease. They took volunteers and broke them into three groups: The first was advised to exercise at low amount/moderate intensity (equivalent to walking 12 miles per week). The second was asked to exercise at low amount/vigorous intensity (jogging 12 miles per week). The third was set to high amount at vigorous intensity (jogging 20 miles per week - 75% VO2max). With these three groups they assessed the effect of the different programs on the volunteers’ risk factors for metabolic disease over the course of six months.

Their findings were a mix of good and bad news. The good news was, participants were able control their diabetes and heart disease risk by exercise. The bad news was, it took a lot of exercise to achieve meaningful results. Dr. Slentz and colleagues measured the LDL particle number, LDL particle size and the HDL size in the subjects. They also looked at visceral fat (waist circumference), and the amount of exercise needed just to lose some weight. They then plotted the improvement in these numbers against a baseline sedentary group to calculate how much exercise it takes to “break-even.” They asked, "how much do people need to exercise before they begin to achieve a meaningful improvement in each of these parameters?"

Miles per week needed before improvement begins:

Fat mass...................4

LDL size....................7

Lose weight...............8

HDL.........................10

Visceral fat...............13

LDL #......................13

These were the minimum amounts needed to see any effect at all. After this "break-even" number, the improvement curves rose fairly swiftly in the positive direction with a general “more is better” relationship to the number of miles. What they found when they looked specifically at the measures most closely related to diabetes (triglycerides, insulin resistance and a metabolic score) was that walking seemed to improve those factors more than running. They didn’t examine why, but speculated that the difference was likely due to differential treatment of the fat energy in the liver or through increased lipoprotein lipase activity.

The amount of exercise a person thinks of as “a lot,” is, of course, relative. Perhaps 13 miles sounds like a minimal weekly amount of walking or jogging to some, but I would counter that would only be to someone who isn't obese and doesn’t work with very obese patients. If I had recommended 2 miles a day as the minimum dose of exercise to get measurable risk reduction to my patients, a good deal would have answered that if they could walk two miles a day, they wouldn’t need to come see me at all! And would have agreed.

So exercise doesn't easily translate to weight loss in individuals. But surely if you get large groups of people to increase exercise, you can detect an improvement in population health over time. Right?

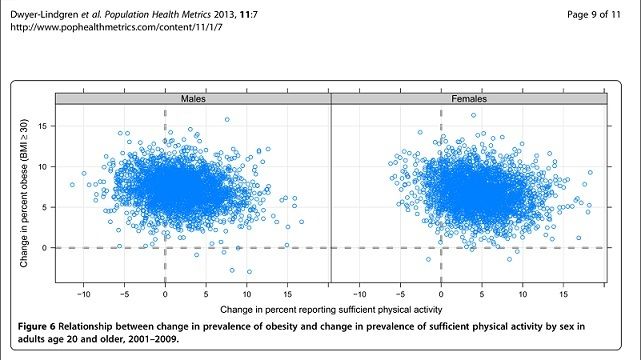

This hypothesis was examined in an interesting analysis was published by Ali Mokdad's group in 2013, which showed that increasing physical activity rates on a county by county basis did not have a beneficial effect on obesity rates.They took survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to assess how well activity patterns correlate with obesity patterns by county, comparing changes over ten years.

What they found is that there is almost no correlation between rising activity levels in particular counties and improvements in obesity rates in those counties. They concluded that “for every 1 percentage point increase in physical activity prevalence, obesity prevalence was 0.11 percentage points lower.” Unfortunately, they don't explain, “lower than what,” but by reading the paper several times I deciphered that they meant “lower than the rise in obesity that would have been expected.” So they are talking about a very slight decrease in the rate of increase in obesity, for those counties that saw more physical activity over ten years. As they reported a 10:1 ratio cause to effect, it is safe to say that the study showed essentially no value, in terms of county level obesity rates, attributable to increasing activity levels in any county over a ten year period.

Source: Creative Commons Open Access Article

The above appears like a demo graph you would use in a statistics class to demonstrate what it looks like when two factors do not have anything to do with each other. When things correlate, you have a nice thin line pointing in a particular direction with dots clustered along the trend. What we have here are two enormous blobs, similar to what you would see if you plotted, say, individual's incomes related to their hemoglobin. Simply no relationship at all.

They didn’t say that counties with more exercisers didn’t have a lower baseline obesity rate (they generally do), but simply that the cause and effect you might wish for if you were applying for a grant (like, that your plans to build bike paths will reduce the county obesity rate) is hard to find in the data. We don’t know if all those people in Douglas County, Colorado (which had the lowest obesity rates and highest exercise rates) are skinny because they hike and bike so much or whether all the skinny people that live there happened to be hikers and bikers who moved to Colorado to do that stuff. We don't know anything about the reasons behind the baseline correlations. What we do know is that the counties that saw the biggest increase in activity over a decade did not become skinny and those that decreased activity did not become heavier than expected.

These results were worth publishing and I bring them into the discussion here because they are surprising: the proposition that we should exercise more to decrease obesity rates seems like it would be so clear that you are almost testing a tautology. This comes from our conflating fitness with weight loss. We use obesity as the inspiration for bike paths and trail building and public health campaigns to get people outside, assuming that exercise has to be a good thing. However, it has little to do with weight one way or another: not on an individual level, not on a county level and not on a national level. If we decide that exercise is something universally good and want to promote it, then it needs to be for its own sake, not as a response to the obesity epidemic.

Can you lose weight if you don't move at all?

When I was a resident, an experienced supervising doctor told me that the thrill of medicine was that every few weeks, as you see your 20-30 patients a day and do your job, you will stumble upon something that matters. You will check a lab, do an xray, or double-check something you notice on exam. Every few weeks you will catch something that another doctor might have missed, not because you are better, but just because you are paying attention at the right time. In those occasional moments, you prove the whole enterprise to be worthwhile, because you change someone's health, maybe even save their life.

I thought he was an idiot. The idea of doing real medicine, solving a mystery and saving the day only once a month or so sounded like a pretty bad deal to me. "This guy must not be very good at what he does," was my dismissal of it.

Turns out, my experience has pretty much lived up to what he projected. I bring it up here, because one of the rare lucky moments for me, of actually making a difference, was meeting a weight loss client who had recently become wheelchair bound from weakness and shortness of breath. Her family brought her to me for an initial consultation, but it was obvious that she wasn't short of breath from her weight. She was sick. Very sick. When I listened to her lungs, I heard. . . almost nothing at all. Instead of leaving with a notebook and a diet plan, that family left with a note from me to the ER staff across the street in the hospital and orders for tests, with a good chance of being to be admitted overnight. This had taken some negotiating with the patient, who thought I was a lunatic. I assured her that ER staff and hospital's internal medicine doctors would evaluate her and send her home if I was being too rash.

As it happened, she had waited too long already. Labs showed infection in the blood and that same evening, her lungs, which were shutting down from acute respiratory failure due to whole body infection, gave out, causing her to be intubated, placed on a respirator. Other organs followed and by the time I came to visit her a few days later, I was surprised to find her in the intensive care unit, in a coma. I asked some questions of the nurse. The family wasn't there. I had only met her once and there was nothing for me to do. She needed a weight loss doctor like a hole in the head. I followed her a bit on the shared computer system we had with the hospital, but it went on for weeks and I finally lost track of her.

Several months later, she came to visit me in clinic. "I just wanted to say thank you for saving my life. You were smart to see how sick I was."

"A monkey could have seen how sick you were," I replied, "but thank you."

"The coma did wonders for my figure, huh?" she said, spinning a little. It was true, she was half the woman I'd met six months before. I hadn't recognized her at first. "Three months in a coma, two more recovering in bed, finally got moving about three weeks ago and wanted to come see you."

"How many pounds have you lost?" I asked

"About 150 last time we checked." she answered.

We finished our conversation and I realized an important lesson: if you can control what goes into a patient, they will lose any amount of weight you wish.

If exercise doesn't work, how about activity?

From the discussion the above, we can reject the notion that weight loss comes from a gym membership. But before we go dismissing the calorie burning side of the energy equation altogether, we should consider an aspect of movement that actually does have real merit and some good scientific reinforcement.

I have noticed, on many occasions, while taking a patient's weight history, that jobs seem to make a difference. It is common for people to tell me that they lost 30 pounds after taking a job in construction, or that they gained 30 pounds when they got promoted to supervisor and had to sit at a desk all day. Truck drivers have inordinately high rates of obesity, with good reason: they are literally paid to sit still.

This type of change is not dealing with "exercise" but with the all day measure of physical activity and "NEAT." James Levine, a doctor at the Mayo Clinic has done more to popularize the idea that daily movement is important for weight control than any other researcher. While he didn't "discover" the concept of "non-activity thermogenesis," he has led the research into its assessment and popularized it as a concept.

His clearest scientific explanation of energy balance was in a 2004 paper for the American Journal of Physiology. In it, he shows that the basal metabolism (RMR in the equation) and the DIT (energy for digesting food) fluctuate very little. But the NEAT can be as little as 15% in a sedentary person up to 50% of total energy in a very active person. Dr. Levine argues that "for the vast majority of dwellers in developed countries, exercise-related activity thermogenesis is negligible or zero." Thus, all "PA" can be subsumed into the term "NEAT." He then compares the energy lost to various activities lost due to modernization. It's a philosophically pleasing idea: modern life has made us heavy by making things too easy.

If life is too easy in our modern environment, then the solution would be to find ways to make it harder again. Levine published his sentiments on this subject in a 2009 book entitled "Move a Little, Lose a Lot," which unfortunately reads like a very sober scientist accidentally swallowed his hospital's marketing department. But style points aside, he makes a very forceful and compelling argument that our approach to all day living, rather than our approach to exercise, can make a difference for weight. He relates the story of how he personally realized the importance of NEAT by analyzing the movements of naturally lean and naturally obese subjects. The lean individuals burned 300+ calories more per day in incidental movements, mostly standing and walking. He then argues that this is enough to account for the difference between individuals' variability in responses to weight loss interventions.

It's hard to argue with the few data points he presents. But his conclusions: that we should incorporate standing work stations, take our meetings walking and even read his book while pacing (he honestly recommends this) seems a bit bizarre to me and reminiscent of anorexia sufferers. He describes his lab as a hive of restless activity, where everyone stands, walks and fidgets through all productive activity, presumably when they are not annoying their co-workers by jiggling on an exercise ball in lieu of a chair. He suggests a treadmill in front of the TV at home and has designed a treadmill desk. I think he, and all the "get moving" advocates out there, is missing two important points:

1. People have different set points for activity, just as they have different set points for hunger and different internal metabolisms.

2. Some of us are already compulsive and being directed to move as much as possible might provoke exercise addiction and worsen eating disorders.

With regard to the first point, I speculate that the Mayo Clinic NEAT laboratory is largely filled with the already fit and "used to be fit, but just need to get back into it" crowd that is common in medical academia. His book gives a couple examples of heavier patients seeing real improvements in health parameters, but the majority of the case study examples involve people losing 10 or 15 pounds and feeling great. I suspect he is preaching to the converted for the most part (to be fair and honest, I would put myself in that already converted/already wired for restlessness crowd) and that few truly obese patients will get much from his recommendations.

The medical literature supports that we are all wired differently with regard to activity. In a recently published trial in the journal Obesity (Herrmann, 2015), researchers assigned a group of 74 overweight and obese adults to a five day per week exercise regimen for 10 months. The outcomes, as in most studies, were variable, in terms of amount of weight lost from the program. To further describe this natural variability, the researchers divided the participants into "responders" and "non-responders" to the intervention by whether they lost more than 5% of body weight. They showed that responders were able to eat less, burn more energy between sessions and also increase non-exercise activity. The "non-responders" (about half of the group) were the people whose natural response was to decrease activity between sessions, naturally slow metabolism and eat a bit more to make up for the exercise. This argues that whether we are going to feel great and get fit with an instruction to move may not be something we can choose.

Many of my patients seemed to grasp this intuitively. I became so indifferent to exercise as a contributor to weight problems, that I ceased asking about it, except when a new exercise idea was proposed by a patient. I would usually respond with "well, did you used to work out a lot, when you were lighter?" If the answer was "No" I would generally support not relying on exercise now. If the answer was "Yes, I used to be a jock," then I generally supported starting back into it. It seemed very likely to me that grade school gym class had already sorted out personal talents and predilections with regard to athletics. As I ventured to put it to a fifty year old gentleman who was a good 200# pounds heavier than his high school weight: "I think if you were meant be a marathoner, you'd have seen signs of it before now."

As to the second concern I raise above, about exercise addicts, I would recommend this TED talk from Zoe Chance wherein she describes her addiction to her pedometer (STRIVE) which goaded and provoked her into becoming a stair climbing, pacing maniac whose life became an obsessive relationship with her device and her step count:

https://youtu.be/AHfiKav9fcQ

I find it a remarkable oversight on Dr. Levine's part that his book doesn't mention exercise addiction, compulsive lifestyle data checking, obligatory running, or anorexia. I would be quite surprised if none of his whirling, whizzing, frenetic colleagues and patients are not subject to some of these difficulties, which can be worse, in the end, than obesity. While I agree that trying to increase all-day activity, makes more sense than trying to burn calories for an hour in the gym, I continue to think that it is not the difference between the heavy and the lean. I think it's more likely the difference between the lean and the leaner.

Not everyone is an athlete. That's OK. But when I try to gently move the conversation with patients away from exercise and toward food issues, I always sense some disappointment. The fact is that losing weight is about "getting healthy" for most patients. Even knowing that exercise can't burn enough calories to matter, most people want to include exercise in a weight loss effort because the drive for thinness is an attempt to feel better. People assume that those who exercise feel better than those who don't. I don't argue with that logic.

In my practice, after years of internally debating what's best, I settled on a simple counseling pattern that worked for most of my patients: Exercise if it makes you feel good, don't exercise if it makes you feel worse, or if you can't get into a groove. Focus on increasing walking distance over time with the goal of eventually being able to walk as much as you want without weight limiting you. Be aware that your diet approach has to work in sickness and in health, which includes orthopedic injuries that can keep you out of the gym for months. Just like with diet, try to utilize ideas that are possible to maintain for the long term, hopefully a lifetime.

References:

Slentz, C. et. al. Exercise, abdominal obesity, skeletal muscle and metabolic risk: evidence for a dose response. Obesity 2009; 17 (supp3).

Dwyer-Lindgren, L. et. al. Prevalence of physical activity and obesity in US counties, 2001-2011: a road map for action. Population Health Metrics 2013 11(7).

Thomas, DM. et al. A Mathematical Model of Weight Change with Adaptation. Math Biosci Eng. 2009 October; 6(4): 873-887.

Curioni, CC. Lourenco, PM. Long-term weight loss after diet and exercise: a systematic review. International Journal of Obesity 2005; 29(10): 1168-1174.

Thorogood A. et. al. Isolated aerobic exercise and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Medicine 2011; 124 (8): 747-755.

Levine, JA. Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism 2004; 286(5): E675-E685.

Levine, JA. Move a Little, Lose a Lot. Crown Publishing, New York. 2009.

Herrmann SD. et. al. Energy intake, nonexercise physical activity, and weight loss in responders and nonresponders: The Midwest Exercise Trial 2. Obesity 2015; 23(8): 1539-1549.

Comments