The 42 gathered gods would measure the heart and if it weighed more than the Feather of Truth which adorned the head of Maat, their Goddess of Justice, Order, and Truth, it was consumed by the Goddess Ammit, Devourer of the Dead, who had the body of a crocodile, a lion, and a hippopotamus, and you were gone from existence forever.

People had a lot of ways to get heavy hearts. Theft, anger, even eavesdropping added weight.

To try and improve the chances for the deceased going to Aaru - heaven - instead, the living family might include an ornamental Scarabaeus sacer, a crafted dung beetle, included in Spell 30 from the "Book of The Dead" and imploring the heart not to weigh too much.

They had a whole book of spells because even getting to the tribunal was the best Dungeons&Dragons adventure ever. First, you weren't just a corporeal form, you were an amalgam of body, heart, name, and spirit, so the Book of the Dead had spells to keep you together. Providing water and air and food so your body doesn't atrophy, for example, and Spell 30 to keep your heart light. The journey to the netherworld risked losing some or all of those components, because the trials you needed to endure included perils much like the physical world, only more dangerous. If insects and snakes didn't get you, giant crocodiles would try.

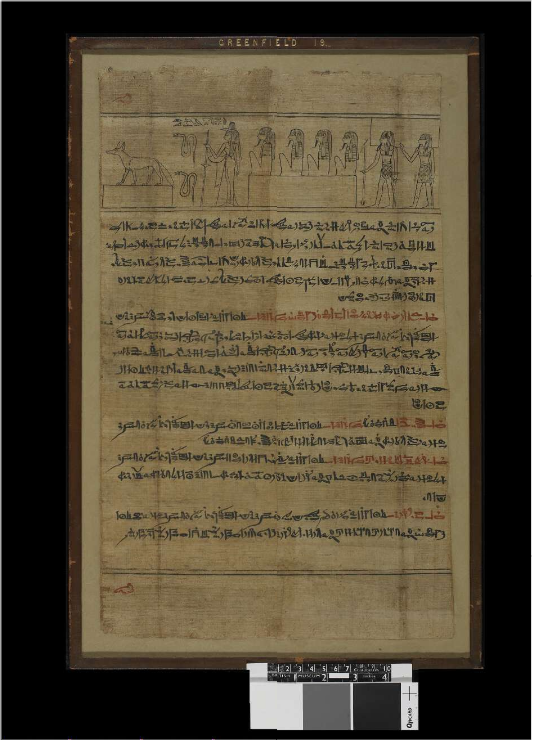

When you arrived at the gate of Duat, you had to answer questions correctly or those gods would attack you. Any mistakes at all and Oblivion was the result. Obviously a lot could go wrong. The Book of the Dead was important but expensive, so only the wealthy possessed them. The longest still in existence, called the Greenfield Papyrus, measures over 100 feet.

Book of the Dead of Nestanebetisheru frame 19. Courtesy of the British Museum.

Compared to modern western lore like H.P. Lovecraft's Book of the Dead, the Necronomicon, the Egyptian one is downright sunny. His tome is only described in the abstract, but statements like "Shub-Niggurath! As a foulness shall ye know Them" tell you there's no heavenly ending happening anywhere in his deadly world of 100 years ago. That clearly had previous works to go on, as did Dante's "Divine Comedy" but that doesn't explain why the Popol Vuh of the Maya and the Mesopotamia's Inanna's Descent have such similar themes, despite no way for their to have been cultural exchange between them. Judaism and Islam have neither of those journeys while while Greeks share a lot with Egyptians and Christians about the journey to the next life.

One thing they all do share is that to ascend, you must be judged, and we should all be nicer people. That's an important message today, like always.

Comments