Remind you of your high school gym teacher? Click to play a video of how Todorov’s lab alters “face space” to vary the expressions characteristic of a dominant person.

We often form spontaneous, rapid, and impactful opinions about the characteristics of other people based on our interpretation of a single, static sample of their appearance. We judge people for characteristics such as likability, trustworthiness, competence, and aggressiveness, just based on their appearance.

A crucial question, asks Todorov's lab, is whether appearance-based inferences are accurate, because these evaluations can dictate important social outcomes, ranging from electoral success to sentencing decisions.

In the August 12th edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), Todorov's lab published a study which suggests that humans have "adaptive mechanisms for inferring harmful intentions, which can account for rapid, yet not necessarily accurate, judgments from faces."

If you think you're good at summing someone up, play around on the WhatsMyImage website to see if you actually can tell how smart someone is based on their picture. On this site, users submit their own picture, and have other people try to guess facts about themselves--like GPA, whether they've been arrested, or number of sexual partners--all based on their picture.

Christopher Olivola, a fourth-year graduate student in the lab, has analyzed over 1 million appearance-based judgments from this site, and has found that, overall, people do a pretty bad job when it comes to judging people based on appearances.

Todorov's lab has published some amazing findings relating to how these decisions actually affect political elections.

Remind you of your high school gym teacher? Click to play a video of how Todorov’s lab alters “face space” to vary the expressions characteristic of a dominant person.

We often form spontaneous, rapid, and impactful opinions about the characteristics of other people based on our interpretation of a single, static sample of their appearance. We judge people for characteristics such as likability, trustworthiness, competence, and aggressiveness, just based on their appearance.

A crucial question, asks Todorov's lab, is whether appearance-based inferences are accurate, because these evaluations can dictate important social outcomes, ranging from electoral success to sentencing decisions.

In the August 12th edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), Todorov's lab published a study which suggests that humans have "adaptive mechanisms for inferring harmful intentions, which can account for rapid, yet not necessarily accurate, judgments from faces."

If you think you're good at summing someone up, play around on the WhatsMyImage website to see if you actually can tell how smart someone is based on their picture. On this site, users submit their own picture, and have other people try to guess facts about themselves--like GPA, whether they've been arrested, or number of sexual partners--all based on their picture.

Christopher Olivola, a fourth-year graduate student in the lab, has analyzed over 1 million appearance-based judgments from this site, and has found that, overall, people do a pretty bad job when it comes to judging people based on appearances.

Todorov's lab has published some amazing findings relating to how these decisions actually affect political elections.

"...overall, people do a pretty bad job when it comes to judging people based on appearances."

In 2007, Todorov and colleague Charles Ballew showed that rapid judgments of candidates' competence based solely on their facial appearance predicted the outcomes of gubernatorial elections. Using these findings, they were able to predict 68.6 percent of gubernatorial race outcomes, and 72.4 percent of Senate races. They showed that predictions were as accurate after a 100-ms exposure to the faces as they were after unlimited time exposure. Asking participants to deliberate and make a good judgment not only dramatically increased the response times, but also reduced the predictive accuracy of the judgments. Not only do we make these snap judgments every day, but we are also pretty confident in the accuracy of our judgments--a finding that has important implications in both politics and economics. Olivola, who describes his research as being "at the intersection of psychology and economics," asks, "should we continue to rely on making decisions based on appearances, or should we actually be taking steps to ignore them?" "If people use faces or appearances to draw their impressions of others," he explains, "they must be doing that because they think those assumptions are correct. If you couldn’t get any good information from appearances, then a rational person wouldn’t use this information to make their decisions." But Todorov's lab has shown is that people clearly are using faces and appearances to make decisions.

"Asking participants to deliberate and make a good judgment not only dramatically increased the response times, but also reduced the predictive accuracy of the judgments."

In one experiment, Todorov's lab showed people several faces that differed on abstract dimensions with no real psychological meaning--things like the width of the cheeks, the length of the face, the size of the nose, or other shape dimensions--and the participants were asked to rate these faces on how trustworthy they appeared. Using the participants' results, Todorov's lab was able to vary the shape of the face--something they refer to as "face space"--so so that the face would have the maximum impact on how trustworthy the people thought it appeared to be. The interesting thing is that when you go to extreme lengths to make a face appear trustworthy, the face appears as if it’s smiling. And when you go to extreme lengths to make a face appear untrustworthy, it appears as if is angry. The most important question that the lab asked--and answered with this research--was "what about that face is making people say it looks trustworthy or untrustworthy?" So far their results have suggested that the brain system which recognizes emotions may be overgeneralizing to a neutral face, so that a neutral face with just a hint of anger is going to look untrustworthy, and a neutral face with just a hint of smile is going to look trustworthy. (By the way, for neuroscientists interested, the direction in "face space" of maximal trustworthiness change was entirely constrained by the trustworthiness ratings that people assigned to a set of randomly generated faces). Chris Said, a graduate researcher in the lab, carried out one of the first studies to test this hypothesis. He used a computer program that would classify emotions based on pictures of real faces that were inputted into the program. But instead of submitting emotional faces to the program--for example faces that appeared defiant or sad--he submitted neutral faces to this classifier and forced it to identify an emotion on a seemingly emotionless face.

Chris Said inputted neutral faces into a computer program and forced the program to decide whether the face was trustworthy or untrustworthy. While the neutral face above is computer-generated, Chris used pictures of real faces for his experiment.

It turns out that when the classifier detects only a slight amount of anger in a face, people tend to think that this is an aggressive and untrustworthy face. When the classifier detects only a slight amount of a smile, people tend to think it’s a trustworthy or caring face.

And when the classifier detects fear, people think the face isn't very intelligent. So next time your least favorite politician appears on the front page of the Times looking like he's just realized his zipper is undone, don't be surprised if you're first snap judgment is "what an idiot."

But perhaps we shouldn't give too much credence to these snap judgments. While such judgments may be primitive and instinctual--and thus "feel" right, the brain's a pretty complicated organ.

Most cognitive neuroscientists have realized that it is difficult to assign a specific emotional or behavioral function to a specific structure of the brain, because functions tend to be very overlapping and complicated, and depend on other factors such as the task and the circumstances.

One primitive structure in the brain, the amygdala, has typically been thought to have evolved as a "fear detector." That is, when you show someone a picture of a fearful face, the amygdala lights up more so than for a neutral face.

Chris Said inputted neutral faces into a computer program and forced the program to decide whether the face was trustworthy or untrustworthy. While the neutral face above is computer-generated, Chris used pictures of real faces for his experiment.

It turns out that when the classifier detects only a slight amount of anger in a face, people tend to think that this is an aggressive and untrustworthy face. When the classifier detects only a slight amount of a smile, people tend to think it’s a trustworthy or caring face.

And when the classifier detects fear, people think the face isn't very intelligent. So next time your least favorite politician appears on the front page of the Times looking like he's just realized his zipper is undone, don't be surprised if you're first snap judgment is "what an idiot."

But perhaps we shouldn't give too much credence to these snap judgments. While such judgments may be primitive and instinctual--and thus "feel" right, the brain's a pretty complicated organ.

Most cognitive neuroscientists have realized that it is difficult to assign a specific emotional or behavioral function to a specific structure of the brain, because functions tend to be very overlapping and complicated, and depend on other factors such as the task and the circumstances.

One primitive structure in the brain, the amygdala, has typically been thought to have evolved as a "fear detector." That is, when you show someone a picture of a fearful face, the amygdala lights up more so than for a neutral face.

"...when you go to extreme lengths to make a face appear trustworthy, the face appears as if it’s smiling. And when you go to extreme lengths to make a face appear untrustworthy, it appears as if is angry."

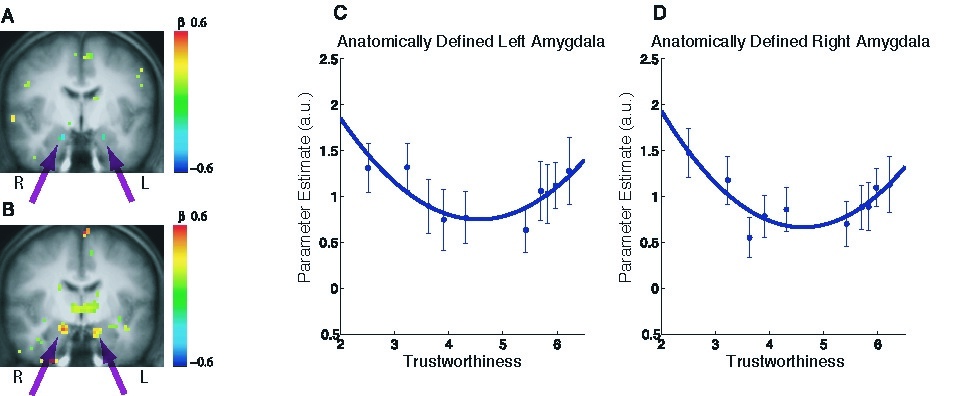

The notion of the amygdala as a "fear detector" now appears to be only partly true. One of Said's recent experiments, which will be published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, found the following: not only does the amygdala respond to extremely untrustworthy faces, it also responds to extremely trustworthy faces. So if you were to plot the amygdala response on the Y-axis, and trustworthiness on the X-axis, you would get a U-Shaped curve--the amygdala responds significantly to very trustworthy faces, and significantly to very untrustworthy faces, but not so much to faces in the middle (a finding which has been shown previously for attractiveness).

The U-Shaped Curve for amygdala response to trustworthy and untrustworthy faces.

Said explains that "there is a tendency in our field to do what is described as the 'reverse inference': you see that a particular brain region is active, and from this you make an inference about the person's psychology or emotional state. For instance if I see that the amygdala is active, I might infer that the person is afraid. However, if the shape of the curve is U-shaped, this is not a valid inference to make."

It turns out that while we do make them, split-second judgments about how trustworthy a face is or how intelligent a face is are not very accurate.

"But people think they are," adds Said. "When you see someone and you think 'I can tell he’s smart,' most people are actually pretty confident in their own judgment. But it turns out that you’re not really accurate most of the time. And if our theory is correct, it turns out that, among other things, your system for detecting emotions is inappropriately overgeneralizing."

If this seems like it's in contrast to Malcolm Gladwell's book "Blink: The Power Of Thinking Without Thinking," it turns out that there are differences between judgments made after seeing a live person moving around and interacting, and judgments made from seeing a photograph. Want to judge the Todorov Lab based just on a photograph? Click here!

The U-Shaped Curve for amygdala response to trustworthy and untrustworthy faces.

Said explains that "there is a tendency in our field to do what is described as the 'reverse inference': you see that a particular brain region is active, and from this you make an inference about the person's psychology or emotional state. For instance if I see that the amygdala is active, I might infer that the person is afraid. However, if the shape of the curve is U-shaped, this is not a valid inference to make."

It turns out that while we do make them, split-second judgments about how trustworthy a face is or how intelligent a face is are not very accurate.

"But people think they are," adds Said. "When you see someone and you think 'I can tell he’s smart,' most people are actually pretty confident in their own judgment. But it turns out that you’re not really accurate most of the time. And if our theory is correct, it turns out that, among other things, your system for detecting emotions is inappropriately overgeneralizing."

If this seems like it's in contrast to Malcolm Gladwell's book "Blink: The Power Of Thinking Without Thinking," it turns out that there are differences between judgments made after seeing a live person moving around and interacting, and judgments made from seeing a photograph. Want to judge the Todorov Lab based just on a photograph? Click here!

When in doubt, smile! Click to play a video of the continuum of characteristic expressions from trustworthy to untrustworthy.

For other publications by Alexander Todorov, click here. He's written on everything from how to eliminate false trait associations, to the psychology of long term risk (with a special focus on climate change).

If you would like your lab to be considered for a profile on scientificblogging.com, e-mail Matthew@scientificblogging.com

When in doubt, smile! Click to play a video of the continuum of characteristic expressions from trustworthy to untrustworthy.

For other publications by Alexander Todorov, click here. He's written on everything from how to eliminate false trait associations, to the psychology of long term risk (with a special focus on climate change).

If you would like your lab to be considered for a profile on scientificblogging.com, e-mail Matthew@scientificblogging.com

Comments