Happy the elephant’s story is a sad one. She is currently a resident of the Bronx Zoo in the US, where the Nonhuman Rights Project (a civil rights organization) claims she is subject to unlawful detention. The campaigners sought a writ of habeas corpus on Happy’s behalf to request that she be transferred to an elephant sanctuary.

Historically, this ancient right which offers recourse to someone being detained illegally had been limited to humans. A New York court previously decided that it excluded non-human animals. So if the courts wanted to find in Happy’s favor, they would first have to agree that she was legally a person.

It was this question that made its way to the New York Court of Appeal, which published its judgment on June 14. By a 5-2 majority, the judges sided with the Bronx Zoo. Chief Judge DiFiore held that Happy was not a person for the purposes of a writ of habeas corpus, and the claim was rejected. As a researcher who specialises in the notion of legal personhood, I’m not convinced by their reasoning.

DiFiore first discussed what it means to be a person. She did not dispute that Happy is intelligent, autonomous and displays emotional awareness. These are things that many academic lawyers consider sufficient for personhood, as they suggest Happy can benefit from the freedom protected by a writ of habeas corpus. But DiFiore rejected this conclusion, signaling that habeas corpus “protects the right to liberty of humans because they are humans with certain fundamental liberty rights recognized by law”. Put simply, whether Happy is a person is irrelevant, because even if she is, she’s not human.

This might seem sensible, but it bears no relation to the legal authority DiFiore used to support her conclusions. Just two pages previously, she referred to Article 1, section 6 of the New York state constitution which claims it is “[t]he right of persons, deprived of liberty, to challenge in the courts the legality of their detention”. No mention of human beings here at all.

Her second reason, on page ten, endorses the view that you must be able to understand and bear duties in order to have a right. This seems logical, and is built on the idea that, as members of a society, we are all bound by a social contract. My right not to be assaulted implies a duty on your part not to assault me. But, of course, we do give rights to those incapable of understanding duties – newborn babies being one example.

The third reason follows what’s called a slippery slope argument. If the Court of Appeal recognized rights for elephants then it would soon be inundated with claims for the rights of all kinds of animals. This piecemeal approach, it’s argued, could destabilize society. This may be a pragmatic reason for denying Happy the right to liberty through a writ of habeas corpus, but it’s not a moral one. The whole point of a right to liberty is to protect individuals from majority oppression, which is itself connected to the moral principle of equality. So for DiFiore to prioritize the stability of the status quo is puzzling.

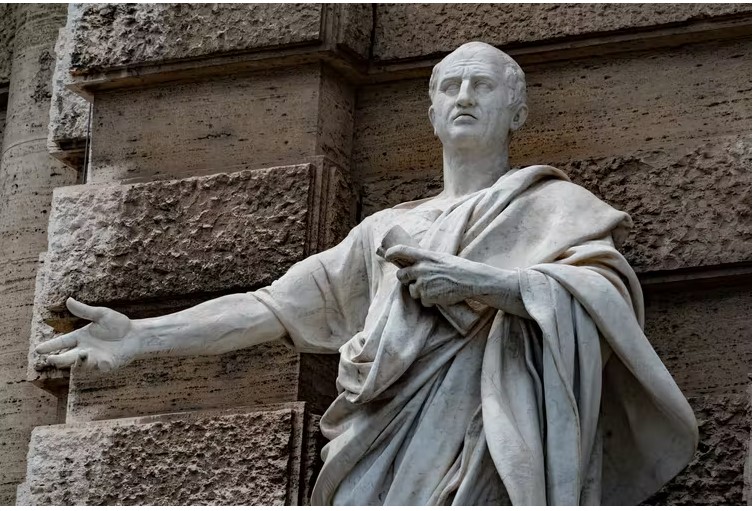

Habeas corpus is reputed to have originated in ancient Roman civil law. Andrea Izzotti/Shutterstock

Equally, a piecemeal approach is not necessarily bad. Courts do case-by-case analyses on a daily basis, particularly in human rights cases where individual rights have to be balanced against the interests of the state. In fact, many legal experts see it as a strength, given it allows courts to address injustices resulting from gaps in legislation – to say when like cases should be treated alike, and differentiate when it is important to do so.

A problem for today

DiFiore reveals in her final paragraph on page 17 that she has no conceptual problem with giving rights to nonhuman beings, but she sees it as a problem for the state government to resolve through legislation. This is a position that US courts have adopted in the past, using it to deny whales and dolphins the right to compensation for disturbances caused by navy sonar.

The problem with this excuse is that legislatures have repeatedly failed to pass legislation to address the problem. As long as they continue to ignore the issue, Happy and other sentient animals continue to suffer from inadequate protection of their interests because they continue to be seen as property. This is something the majority of people would accept as a bad thing. For instance, in a 2017 survey of 2,000 UK pet owners, 90% said their pet was a family member, not property. Living with animals allows us to see their sentience as something that gives them a special status. By refusing to bring the law in line with this, courts are failing to address a clear deficiency.

Forming close ties with animals tends to give people a deeper perspective on sentience in non-humans. Konstantin Aksenov/Shutterstock

This is a problem that will only become more urgent. Recently, a former Google software engineer announced their belief that LaMDA – an AI they worked with – had attained sentience. Although Google disputed this, the rights claims (including the claim to personhood) made by LaMDA in these transcripts do raise serious issues, such as whether it is ethical to undertake certain types of research, like trying to ascertain whether and how LaMDA experiences feelings, without first gaining its consent.

If this abstract issue is a concern, so are specific legal problems that may emerge from sentient AI. Far from being problems for the future, courts in the UK, US and Australia have already considered whether AI can be an inventor for the purposes of a patent registration, and Lord Hodge – Deputy President of the UK Supreme Court – said in a 2019 lecture that there was no conceptual problem with legally recognizing the personhood of an AI.

So why are we speculating about the rights of a sentient AI in the future while ignoring the plight of beings we know are sentient and whose interests are harmed daily? By simply claiming this problem is better resolved by legislation, the New York Court of Appeal simultaneously accepted and deferred the moral case before them.

This position is untenable. Courts aren’t going to be able to hide from it forever. The time has come for them to force the legislature’s hand.

By Joshua Jowitt, Lecturer in Law,Newcastle University.This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments