(Repost from one year ago on the older Genomicron -- this got a nice

response from readers and family, so I am posting it once again.)

In Canada, as in many countries around the world, November 11 is a day of remembrance for the sacrifices made during wartime. In Canada, this refers in particular to World War I (1914-1918) and World War II (1939-1945), but also to smaller engagements in which Canadians were (or are) involved, such as Korea and Afghanistan.

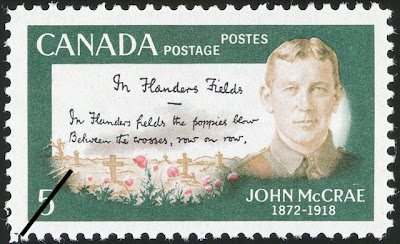

The poppy has be come a symbol of remembrance, and can be found pinned to people's lapels more or less from the beginning of November each year. This tradition, which is also observed in various other nations, is derived from the poem In Flanders Fields by Lt. Col. John McCrae (1872-1918), a Canadian physician and soldier originally from Guelph, Ontario who died of pneumonia while serving in the First World War. The poem was composed shortly after the death of McCrae's friend Lt. Alexis Helmer in the Second Battle of Ypres, and makes reference to Flanders, Belgium, where poppies grew extensively and where many military dead were buried.

come a symbol of remembrance, and can be found pinned to people's lapels more or less from the beginning of November each year. This tradition, which is also observed in various other nations, is derived from the poem In Flanders Fields by Lt. Col. John McCrae (1872-1918), a Canadian physician and soldier originally from Guelph, Ontario who died of pneumonia while serving in the First World War. The poem was composed shortly after the death of McCrae's friend Lt. Alexis Helmer in the Second Battle of Ypres, and makes reference to Flanders, Belgium, where poppies grew extensively and where many military dead were buried.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.— John McCrae

There are several parts of Europe that I am eager to visit on the basis of pride and gratitude for what my fellow Canadians did during the two world wars. Those that I have not been to yet include Vimy Ridge and Juno Beach (Normandy), but I did manage to check one off the list two years ago during a visit to the Netherlands: Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

I was in Leiden to participate in a symposium entitled "Extending the synthesis" that featured a handful of speakers including Rich Lenski, Dave Jablonski, Sergei Gavrilets, Paul Brakefield, John Thompson, Niles Eldredge, and me. On one of the days there were no formal plans, so some of the speakers took a bicycle tour of the beautiful region around Leiden, others headed off the The Hague, and I crossed much of the country by train, by bus, and on foot to visit Groesbeek. It was one of the most meaningful experiences I have ever had.

There is a scene in the movie Saving Private Ryan that never fails to break me up. Actually, there are several such scenes, but the one I have in mind at the moment involves the arrival of a military vehicle at the Ryans' home in which their mother, realizing what this visit must mean when she sees a clergyman exit the car, collapses in grief on her front porch. This grips me with particular force as it happened to my great-grandmother -- twice.

My paternal grandmother grew up in the small town of St. Marys, Ontario, which, like most towns across the country, experienced its share of sacrifice during the Second World War as approximately 10% of the country served (1.1 million out of a population of roughly 11 million). With the labour force severely diminished, my young grandmother worked in a converted hand grenade factory. Two of her older brothers, Bill and Roy, served and died in combat.

To reach the cemetery, one must travel by bus from the nearby town and ask the driver to stop at the road leading to the memorial.

From there, it is a fairly long walk down a forested roadway to another main road, and then another short walk up to the cemetery.

The tombstones are arranged, row on row, in order of burial. My great-uncle Bill's is part of a long line of young men who were lost on the same day. Many of them were probably friends. All were mourned by someone.

My father had previously been the only member of our family to make the trip to see Bill's grave, which he did many years ago. I am sure his experience was as emotional as mine was to be surrounded by so much sacrifice, and to reflect on what this must have meant for my grandmother and her family, and indeed the families of all of the individuals buried here.

Next to the large memorial at the far end of the cemetery there is a tall maple tree. A leaf from this tree hangs in a frame on the wall of my home office. It has often served as an object of reflection for me as a young man who is fortunate that his life has not been affected directly by war.

There is a guest book at the cemetery that invites visitors to leave a message. I spent quite some time leafing through it, and was deeply moved by the messages I read. "Thank you for our freedom" was among the most common. Some 60 years later, the people of the region, and the many who make a pilgrimage like mine to this site, have not forgotten the sacrifices that were made.

None of us should ever forget.

Comments