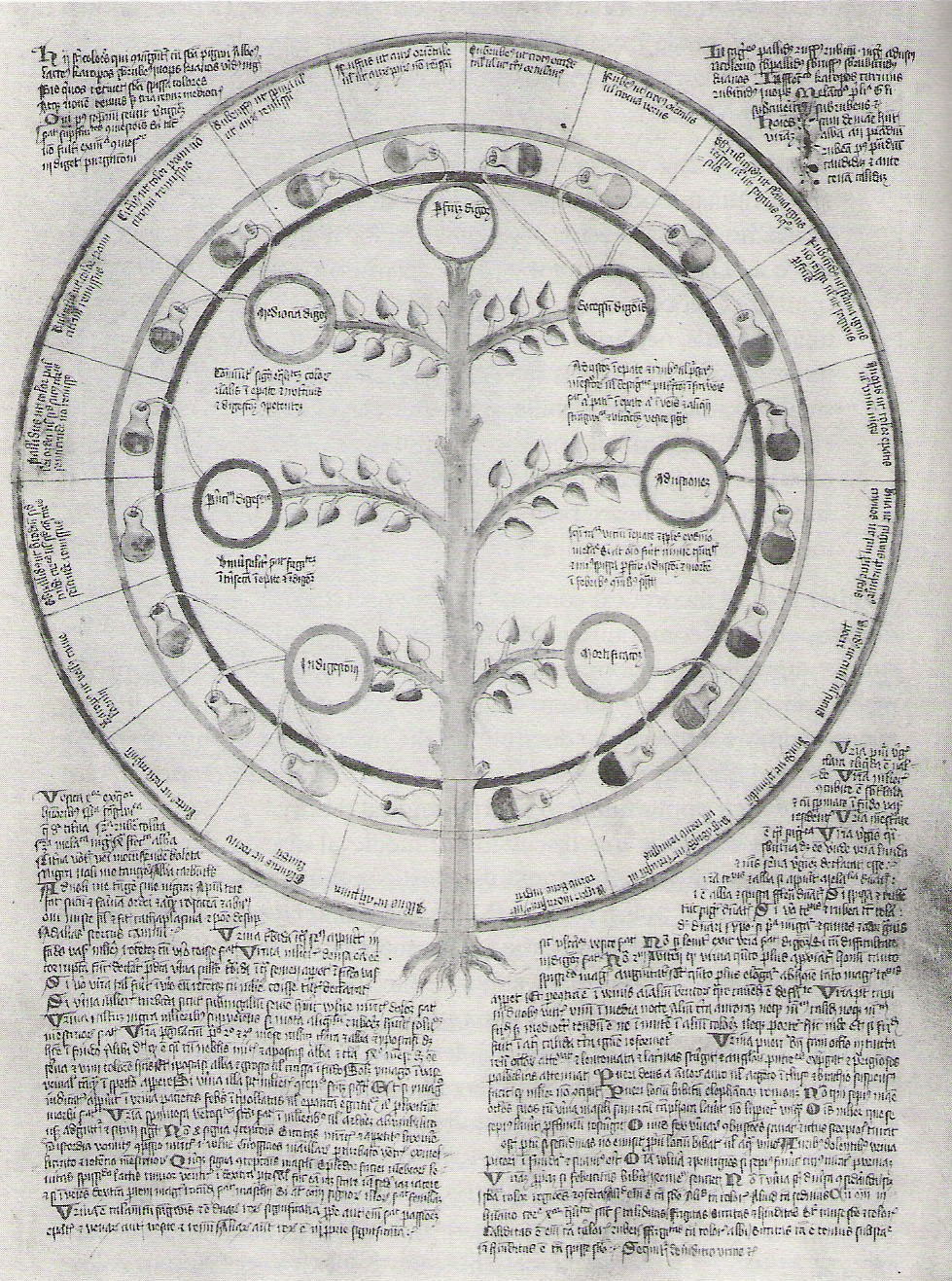

Folk medicine, prayer, astrology, spells, mysticism - your treatment for disease in medieval times mattered most on the beliefs of the people around you rather than a codified study of the body.

It was commonly believed that body health resulted from a balance of the 'humours' in the body - black bile, phlegm and blood and yellow bile- and that a lack of balance meant an issue with a particular organ. Even today those beliefs are prevalent in the use of terms that described them then - if you have ever heard someone described as 'melancholic', it refers to an issue with their spleen resulting in too much black bile.

Many of the practices used then are still in use today. The first thing a doctor does on a modern visit is check your pulse.

David Lindberg, The Beginnings of Western Science, 1992 (pg. 336)

Scholars are gathering next week at the University of Nottingham how attitudes and beliefs that originated centuries ago continue to resonate today. Until recently there was very little study of early medieval health and illness – but research findings are already suggesting that it may be time to re-think the way we regard this key aspect of life in the early Middle Ages.

The two-day conference, ‘Disease, Disability and Medicine in Early Medieval Europe’ brings together leading experts in the field from the USA, Norway, Germany, Israel and the UK on July 6-7, 2007.

Co-organiser Dr Christina Lee, said: “We have to look towards the past to understand the ways in which attitudes towards diseases develop. The success of healing is linked to prevalent cultural views. Ethical codes played a major role in past approaches in dealing with the sick, but today we tend regard most of them as superstition.

“Our own reaction to disease and healing, such as for example the hotly-debated stem cell research, is also linked to contemporary views. By looking at past societies we may be able to understand more about our own attitudes. There is a question of what position the sick and impaired hold within a society or how much illness is accepted as part of life, which may differ from modern views where the prevalent idea is that afflictions should be cured and the expectation that bodies should ‘function’ normally.”

Lectures at the conference include:

• ‘Demon possession in Anglo-Saxon England’, Peter Dendle, Pennsylvania State University, USA. Part of an ongoing study of early medieval demonology and constructs of evil — how prevalent was demonic possession and exorcism and how often did it touch on the day-to-day lives of the Anglo-Saxons"

• ‘Healing from God: physically impaired people in miracle reports’, Klaus-Peter Horn, University of Bremen, Germany. Research focusing on pilgrimages by physically impaired people — and how much help they could receive from relatives, neighbours, servants on the long road to miraculous healing.

• ‘You are what you eat: Christian concepts of the healthy body in Old Norse Society’, Anne Irene Riisoy, University of Oslo, Norway. An overview of the dietary regulations introduced in church legislation in Norway and Iceland, with animals that had been a common feature of the pre-Christian menu — such as horses, cats and dogs — acquiring taboo status.

• ‘”This should not be shown to a gentile”: Medico-magical entries in medieval Franco-German Hebrew manuscripts and their social significance’, Ephraim Shoham-Steiner, Ben-Gurion University, Israel. Includes a discussion of texts detailing short potions, charms and medical remedies in the pages of Hebrew manuscripts.

• ‘Miraculous healing in Medieval Iceland’, Joel Anderson, University of Oslo, Norway. Includes a look at stories of saintly healing miracles and how they were viewed by contemporary Icelandic society, particularly miracles attributed to Bishop Guðmundr Arason ‘the Good’, 1161-1237.

Dr Lee will give a session with the title ‘In good company’, looking at burial patterns of people with disease in Anglo-Saxon England.

Dr Sara Goodacre, of The University of Nottingham, will give a lecture entitled ‘The history of modern Europeans: a genetic perspective’. She will present new data showing geographic trends in patterns of maternally and paternally inherited genetic variation with the British Isles, and what these findings suggest about likely patterns of male and female migration.

The meeting, sponsored by the Wellcome Trust, aims to be a forum for scholars working on the topic in a variety of disciplines and regions of Northern Europe, including all aspects of disease, disability and medicine.

Conference organisers are hoping to build bridges between experts in archaeology, palaeopathology — the study of ancient diseases — the history of medicine, as well as the history of religion, philosophy, linguistic and historical sciences.

The event takes place in the School of English Studies, at The University of Nottingham. It is a collaboration between Dr Lee at Nottingham and Dr Sally Crawford and Robert Arnott, of the University of Birmingham.

Comments