Since the beginning of the industrial age the ocean has absorbed about half of all anthropic(1) carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions into the atmosphere. This has led to an acidification of sea water. Frédéric Gazeau, a scientist at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology, and his colleagues, including Jean-Pierre Gattuso, Director of Research at the Oceanographic laboratory at Villefranche-sur-Mer (CNRS/Université Pierre et Marie Curie) have examined the reaction of oysters and mussels cultivated in Europe to this acidification of the oceans. The results, published in the review Geophysical Research Letters, are beyond doubt. They show for the first time that these economically important molluscs will be directly affected by the radical change underway in the chemical composition of sea water.

Last February the Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Climate Evolution (GECE) noted that global warming “very probably” was a result of green house gas emissions due to human activity. They also emphasized that climate change will accelerate over the course of the 21st century if the emissions remain at the current pace, or increase. Every day over 25 million tons of carbon dioxide combine with sea water, making it more acidic. The increase in CO2 emissions is following an exponential curve. As a result the acidification of the oceans in the coming century risks continuing at a speed of at least one hundred times greater than any natural variation in at least the last six hundred thousand years. The impact of this phenomenon on marine organisms and ecosystems has been ignored for a long time by the scientific community.

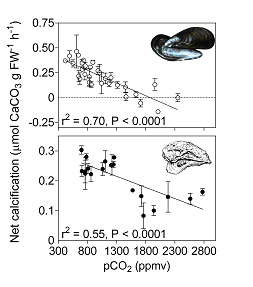

For about ten years now several studies conducted by German, American and French scientists from the CNRS have shown that the acidification of the oceans makes the production of calcium carbonate by marine organisms such as coral, seaweed and phytoplankton more difficult. But no study had been done on commercially important molluscs. The scientists observed that the calcification of the edible mussel (Mytilus edulis) and the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) decreases in a linear fashion with the increase of CO2 and decreasing pH. The speed with which they produce their shells decreases twenty-five and ten percent respectively with the amount of CO2 expected for the year 2100 (approximately seven-hundred and forty parts per million(2) or ppm). In addition, mussel shells dissolve when the partial pressure of CO2 is greater than 1800 ppm. Transferring these laboratory results to the natural world suggests that such a decrease in calcification would most probably have major socio-economic consequences. Indeed, mollusc aquaculture has grown by almost 8 percent a year over the last thirty years reaching production in 2002 of almost 12 million tons a year, translating to a market of 10.5 billion dollars. The Pacific oyster is the most heavily cultivated with a volume of 4.2 million tons in 2002, accounting for 10.8% of global aquaculture production. Mussels represent a production volume of 1.4 million tons a year, accounting for 3.6% of total aquaculture production.

Above and beyond their commercial importance mussels and oysters provide important ecological services. For example, they create habitats which allow for the installation of other species, controlling to a large degree the flow of material and energy. They are also are important prey for the birds which are central to the ecosystem which shelters them. A decline in these species would therefore have serious consequences on the biodiversity of coastal ecosystems and the services they provide to human populations.

For the study to give a precise estimate of the economic and ecological impact of the phenomenon, it is necessary to study the possible long-term genetic adaptation of mussels and oysters to the acidification of the oceans, and also the interaction between acidification and temperature increases predicted by the GECE. These issues will probably be addressed as part of a European project because the European Commission has put out a tender on acidification of the oceans and the consequences, with a budget of 4 to 7 million Euros.

Notes :

1) Resulting from human activities.

2) Unit of measure for carbon dioxide. It was at 280 ppm at the beginning of the industrial era ; now it is approximately 370 ppm, and will be approximately 740 ppm in 2100.

References :

“Impact of elevated carbon dioxide on shellfish calcification” Frédéric Gazeau, Christophe Quiblier, Jeroen M. Jansen, Jean-Pierre Gattuso,

Jack J. Middelburg, and Carlo H. R. Heip,Geophysical Research Letters (GRL) 2007.

Written from a news release by CNRS.

Comments