Astronomers theorize that an as-yet-unidentified form of matter is responsible for 90 percent of the gravity within galaxies and clusters of galaxies but because it is detected via its gravity and not its light, they call it "dark matter."

Astronomers announced earlier this year that Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 imaging suggested that a clump of dark matter was left behind during a clash between massive galaxies clusters in Abell 520, located 2.4 billion light-years from Earth. This dark matter must have collected into a "dark core" that contained far fewer galaxies than would be expected if the dark and luminous matter were closely connected, which is generally found to be the case. This observation was surprising because dark matter and galaxies should be anchored together, even during a collision between galaxy clusters.

A new observation of Abell 520 from another team of astronomers using a different Hubble camera finds that the core does not appear to be over-dense in dark matter after all.

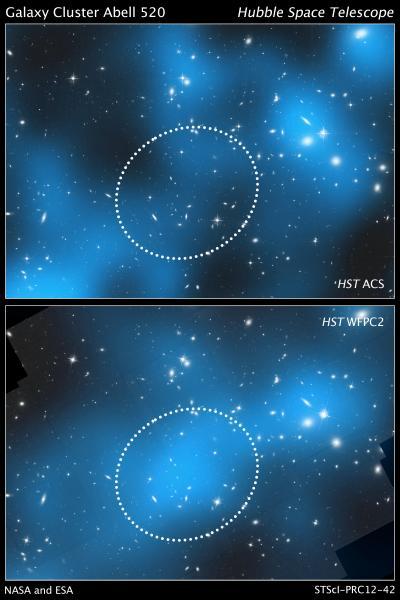

These composite images taken by two different teams using the Hubble Space Telescope show different results concerning the amount of dark matter in the core of the merging galaxy cluster Abell 520. In the top image observations of the cluster, taken by D. Clowe with the Advanced Camera for Surveys mapped the amount of dark matter in Abell 520. It reveals an amount of dark matter astronomers expect based on the number of galaxies in the core. The dark-matter densities are marked in blue, and the dotted circle marks the dark-matter core. The map is superimposed onto visible-light images of the cluster. In the bottom image a second team, led by James Jee, used the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 to find an unusual overabundance of dark matter in the cluster's core, denoted by the bright blue color at image center. Credit: : (top) D. Clowe, (Ohio University, (bottom) J. Jee (University of California, Davis)

Because dark matter is not visible, its presence and distribution is found indirectly through its gravitational effects. The gravity from both dark and luminous matter warps space, bending and distorting light from galaxies and clusters behind it like a giant magnifying glass. Astronomers can use this effect, called gravitational lensing, to infer the presence of dark matter in massive galaxy clusters. Both teams used this technique to map the dark matter in the merging cluster.

"The earlier result presented a mystery. In our observations we didn't see anything surprising in the core," said study leader Douglas Clowe, an associate professor of physics and astronomy at Ohio University. "Our measurements are in complete agreement with how we would expect dark matter to behave."

Clowe's team used Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) to measure the amount of dark matter in the cluster. ACS observed the cluster in three colors, allowing the astronomers to distinguish foreground and background galaxies from the galaxies in the cluster. From this observation, the team made an extremely accurate map of the cluster's dark matter. "With the colors we got a more precise selection of galaxies," Clowe said.

The astronomers estimated the amount of dark matter in the cluster by measuring the amount of gravitational "shear" in the Hubble images. Shear is the warping and stretching of galaxies by the gravity of dark matter. More warping indicates the presence of more gravity than is inferred from the presence of luminous matter, therefore requiring the presence of dark matter to explain the observation. "The WFPC2 observation could have introduced anomalous shear and not a measure of the dark matter distribution," Clowe explained.

Using the new camera, Clowe's team measured less shear in the cluster's core than was previously found. In the study the ratio of dark matter to normal matter, in the form of stars and gas, is 2.5 to 1, which is what astronomers expected. The earlier WFPC2 observation, however, showed a 6-to-1 ratio of dark matter to normal matter, which challenged theories of how dark matter behaves.

"This result also shows that as you improve Hubble's capabilities with newer cameras, you can take a second look at an object," Clowe said.

His team is encouraging other scientists to study its data and conduct their own analysis on the cluster.

Published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Comments