Microscopic spheres of calcium phosphate have been linked to the development of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a major cause of blindness, in a new paper.

AMD affects 1 in 5 people over 75, causing their vision to slowly deteriorate, but the cause of the most common form of the disease remains a mystery. The ability to spot the disease early and reliably halt its progression would improve the lives of millions, but this is simply not possible with current knowledge and techniques.

The paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has implicated tiny spheres of mineralised calcium phosphate, 'hydroxylapatite', in AMD progression. This not only offers a possible explanation for how AMD develops, but also opens up new ways to diagnose and treat the disease.

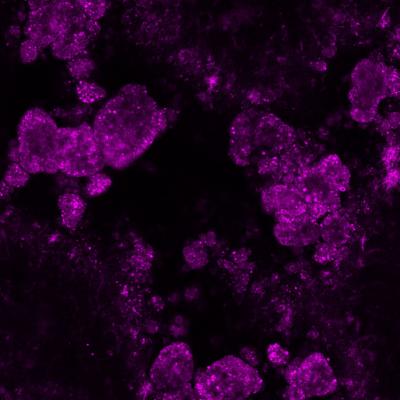

Hundreds of spheres of calcium-based compound hydroxyapatite (in purple), commonly found in teeth and bones. Research has linked these tiny spheres to age-related macular degeneration. Credit: Imre Lengyel, UCL

AMD is characterized by a build-up of mainly protein and fat containing deposits called 'drusen' in the retina, which can prevent essential nutrients from reaching the eye's light-sensitive cells, 'photoreceptors'. Photoreceptors are regularly recycled by cellular processes, creating waste products, but drusen can trap this 'junk' inside the retina, worsening the build-up. Until now, nobody understood how drusen formed and grew to clinically relevant size.

The new study shows that tiny calcium-based hydroxyapatite, commonly found in bones and teeth, could explain the origin of drusen. The researchers believe that these spheres attract proteins and fats to their surface, which build up over years to form drusen. Through post-mortem examination of 30 eyes from donors between 43 and 96 years old, the researchers used fluorescent dyes to identify the tiny spheres, just a few microns - thousandths of a millimeter - across.

"We found these minuscule hollow spheres inside all of the eyes and all the deposits that we examined, from donors with and without AMD," explains Dr Imre Lengyel, Senior Research Fellow at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and Honorary Research Fellow at Moorfields Eye Hospital, who led the study. "Eyes with more of these spheres contained more drusen. The spheres appear long before drusen become visible on clinical examination.

"The fluorescent labeling technique that we used can identify the early signs of drusen build-up long before they become visible with current methods. The dyes that we used should be compatible with existing diagnostic machines. If we could develop a safe way of getting these dyes into the eye, we could advance AMD diagnoses by a decade or more and could follow early progression more precisely."

Some of the mineral spheres identified in the eye samples were coated with amyloid beta, which is linked to Alzheimer's disease. If a technique were developed to identify these spheres for AMD diagnosis, it may also aid early diagnosis of Alzheimer's. Whether these spheres are a cause or symptom of AMD is still unclear, but their diagnostic value is significant either way. As drusen are hallmarks of AMD, then strategies to prevent build-up could potentially stop AMD from developing altogether.

"The calcium-based spheres are made up of the same compound that gives teeth and bone their strength, so removal may not be an option," says Dr Lengyel. "However, if we could get to the spheres before the fat and protein build-up, we could prevent further growth. This can already be done in the lab, but much more work is needed before this could be translated into patients."

"Our discovery opens up an exciting new avenue of scientific research into potential new diagnostics and treatments, but this is only the beginning of a long road." says Dr Richard Thompson, the main international collaborator from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA.

The work was supported by the Bill Brown Charitable Trust, Moorfields Eye Hospital, Mercer Fund from Fight for Sight, and the Bright Focus Foundation. The UCL-led international collaboration involved researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Imperial College London, the University of Tübingen, George Mason University, Fairfax, and the University of Chicago.

Comments