An underwater ridge may be the only thing holding back the retreat of Antarctica's fast-flowing Thwaites Glacier, which drains into west Antarctica's Amundsen Sea, and it could speed up within 20 years, says a new study in Geophysical Research Letters.

Thwaites Glacier is being closely watched for its potential to raise global sea levels as the planet warms but neighboring glaciers in the Amundsen region are also thinning rapidly, including Pine Island Glacier and the much larger Getz Ice Shelf. The study highlights the importance of seafloor topography in predicting how these glaciers will behave in the near future.

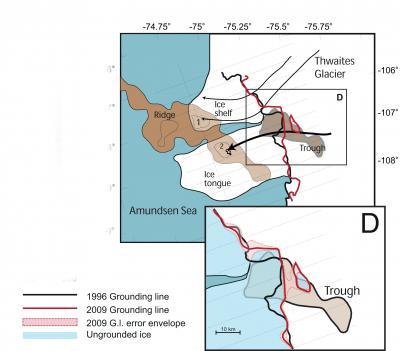

Scientists had previously identified a rock feature off west Antarctica that appeared to be slowing the glacier's slide into the sea. But this study is the first to connect it to a larger ridge, using geophysical data collected during flights over Thwaites Glacier in 2009 under NASA's Ice Bridge campaign. The newly discovered ridge is 700 meters tall, with two peaks—one that currently anchors the glacier and another farther off shore that held the glacier in place between 55 and 150 years ago, according to the authors.

"We didn't know what the sea floor looked like there because the floating ice prevented ships from going into the area," said the study's lead author, Kirsty Tinto, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. The new data, she said, allows scientists to understand what is happening at the glacier's grounding line—where the glacier leaves land and floats into the sea, exposing the ice to warm ocean currents.

The goal of NASA's Ice Bridge campaign is to map the topography of vulnerable regions like this in Antarctica and Greenland by flying over the ice sheets with ice-penetrating radar and other instruments.The discovery that Thwaites is losing its grip on a previously unknown ridge has helped scientists understand why the glacier seems to be moving faster than it used to.

New seafloor topography off Antarctica's Thwaites Glaciers leads scientists to predict accelerated melting in the next 20 years. Credit: Frank Nitsche, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

"In the past, when Thwaites was thicker, the glacier must have been anchored more solidly on that ridge. Now it is not," said Eric Rignot, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who has studied the glacier extensively and was not involved in the study. "Now it is retreating farther inland where we can see other ridges in the ice sounding radar data. Those ridges will determine what will happen next."

As scientists map the contours of the seafloor in the Amundsen Sea region, they are forming a clearer picture of what the glaciers are doing. In 2009, researchers sent a robot submarine beneath Pine Island Glacier's floating ice tongue and discovered a ridge about half the size of the one off Thwaites Glacier. Researchers estimate that Pine Island Glacier lifted off that ridge in the 1970s, allowing warm ocean currents to melt the glacier from below. The glacier's ice shelf is now moving 50 percent faster than it was in the early 1990s, Lamont-Doherty oceanographer Stan Jacobs and colleagues detailed in a study in Nature Geoscience earlier this year. Pine Island Glacier is moving into the sea at the rate of 4 kilometers a year—four times faster than the fastest-moving section of Thwaites.

Lamont-Doherty geophysicist Robin Bell, study co-author, compares the ridge in front of Thwaites to a person standing in a doorway, holding back a crowd. "Knowing the ridge is there lets us understand why the wide ice tongue that used to be in front of the glacier has broken up," she said. "We can now predict when the last bit of floating ice will lift off the ridge. We expect more ice will come streaming out of the Thwaites Glacier when this happens."

"The bathymetry is the roadmap for how warm ocean water reaches the edges of the ice sheet," she added. "Ridges like this one and the one discovered in front of Pine Island Glacier stabilize ice sheets, but can also be a critical part of the destabilizing process."

Thwaites Glacier is currently pinned on the peak of a newly discovered underwater ridge. Credit: Kirsty Tinto, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Comments