Even in deep space, atoms feel the the cosmic microwave background left over by the Big Bang. The cosmos is filled with electromagnetic interactions that show atoms they are not alone. Stray electric fields, like from a nearby electronic device, will also slightly adjust the internal energy levels of atoms, a process called the Stark effect.

Even the universal vacuum, presumably empty of any energy or particles, can very briefly muster virtual particles that buffet electrons inside atoms, further shifting their energies; this form of self-interaction is known as the Lamb shift.

A new calculation by scientists at the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) and the University of Delaware shows how still another influence, the warmth thrown off by nearby objects, can shift energy levels. Uncertainties in this "blackbody radiation shift" will soon impose limits on the accuracy of the best atomic clocks.

Theoretical work on this subject will give scientists extra confidence when they come to redefine the second in coming years, a recalibration based on how ultra-cold atoms behave while sitting in special traps.

Modern timekeeping consists nowadays in reliably counting the cycles of light pouring out of those atoms and, more basic still, knowing what the atoms' intrinsic energy levels should be once all external influences are taken into account. On the experimental side, scientists slow the atoms to a near standstill in traps in order to minimize Doppler effects from the emitted light. This, and the ability to detect and count light oscillations at ever shorter wavelengths ---has led to atomic clocks with uncertainties as small as one part in 1017.

The move from microwaves as the atomic "escapement" for clocks to light in the optical range (harder to measure but offering a precision hundreds of thousands of times better) earned several scientists the 2005 Nobel in Physics. One of 2012's Nobelists, David Wineland, is a pioneer in exploiting the properties of single ion held in a trap to develop clocks of the highest stability.

The precision of the clocks, however, is no better than knowledge of the internal energy levels of the atoms themselves, whether they are single ions or a gas of neutral atoms held in space by a network of laser beams---an arrangement called an optical lattice.

Some of the things that impose unwanted shifts on the atoms in a lattice, such as inter-atom collisions or the Stark effect, can be controlled. According to JQI Fellow Charles Clark, one of the largest irreducible parts in the uncertainty budget of an atomic clock is the blackbody radiation emitted by the very chamber enclosing the atoms. The atoms in the lattice might, by virtue of an elaborate cooling process, be at milli-kelvin or even micro-kelvin temperatures, but the surrounding vacuum chamber is generally at room temperature.

One of the basic laws of thermodynamics says that material objects radiate heat---the higher the temperature the higher-energy the radiation. This shift is hard to measure experimentally and hard to calculate theoretically.

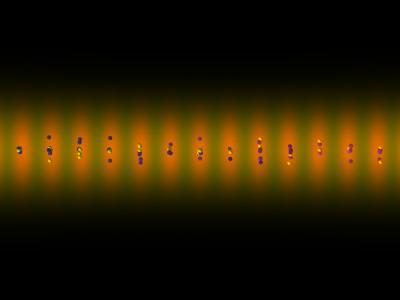

This shows the lattice of laser beams traps small numbers of ytterbium atoms in pancake-shaped "wells." A yellow laser excites the atoms so that they switch between lower (blue) and higher (yellow) energy levels. Credit: NIST

Coming to grips with this faint form of influence is the purpose of a new paper. Clark and his co-authors Marianna Safronova (a JQI Adjunct Fellow) and Sergey Porsev of the University of Delaware, look specifically at how ytterbium atoms are affected by blackbody radiation.

The rare-earth element ytterbium (Yb) is valued not so much for its mechanical properties but for its complement of internal energy levels. "A particular transition in Yb atoms, at a wavelength of 578 nm, currently provides one of the world's most accurate optical atomic frequency standards," said Safronova.

Although only important at a precision level of a part in 1015, accurate knowledge of the blackbody shift is more pertinent now that clocks are closing in on the part-per-1018 level of precision. That is, the uncertainty in the blackbody shift must be comparable to (and eventually lower than) the desired uncertainty of the clock. The new calculation by Safronova, Clark, and Porsev is the best yet since it includes the most complete treatment of the electron-electron correlations within the Yb atoms.

Clark estimates that the amount of uncertainty achieved in the value of an atomic energy level---about 2 times 10-18 --- corresponds to a clock uncertainty of about one second over the lifetime of the universe so far, 15 billion years.

The authors also studied the long-distance interactions among the Yb atoms and atoms of other species as well. This is critical to understanding the physics of dilute gas mixtures in general. Such mixtures are of interest, for example, in studying such things as quantum dipolar material (molecules which, though neutral, possess an electric dipole moment) and many-body quantum simulation. Besides applications in timekeeping and the study of ultracold chemistry, the results of the present work are important for the measurement of the weak force (through subtle parity effects---the process by which nature can tell left from right) and the search for the new physics beyond the standard model of the electroweak interactions.

Comments