Researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab have accelerated subatomic particles to the highest energies ever recorded from a compact accelerator - a laser-plasma accelerator, which is a new class of particle accelerators that can fit on a table.

The team used a specialized petawatt laser and a charged-particle gas called plasma to get the particles up to speed - electrons in this case - inside a nine-centimeter long tube of plasma. The speed corresponded to an energy of 4.25 giga-electron volts. The acceleration over such a short distance corresponds to an energy gradient 1000 times greater than traditional particle accelerators and marks a world record energy for laser-plasma accelerators.

Traditional particle accelerators, like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, which is 17 miles in circumference, speed up particles by modulating electric fields inside a metal cavity. It's a technique that has a limit of about 100 mega-electron volts per meter before the metal breaks down.

Laser-plasma accelerators take a completely different approach. In the case of this experiment, a pulse of laser light is injected into a short and thin straw-like tube that contains plasma. The laser creates a channel through the plasma as well as waves that trap free electrons and accelerate them to high energies. It's similar to the way that a surfer gains speed when skimming down the face of a wave.

A 9 centimeter-long capillary discharge waveguide used in BELLA experiments to generate multi-GeV electron beams. The plasma plume has been made more prominent with the use of HDR photography. Credit: Roy Kaltschmidt

"This result requires exquisite control over the laser and the plasma," says Dr. Wim Leemans, director of the Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division at Berkeley Lab and lead author on the paper. The results appear in the most recent issue of Physical Review Letters.

The record-breaking energies were achieved with the help of BELLA (Berkeley Lab Laser Accelerator), one of the most powerful lasers in the world. BELLA, which produces a quadrillion watts of power (a petawatt), began operation just last year.

"It is an extraordinary achievement for Dr. Leemans and his team to produce this record-breaking result in their first operational campaign with BELLA," says Dr. James Symons, associate laboratory director for Physical Sciences at Berkeley Lab.

In addition to packing a high-powered punch, BELLA is renowned for its precision and control. "We're forcing this laser beam into a 500 micron hole about 14 meters away, " Leemans says. "The BELLA laser beam has sufficiently high pointing stability to allow us to use it." Moreover, Leemans says, the laser pulse, which fires once a second, is stable to within a fraction of a percent. "With a lot of lasers, this never could have happened," he adds.

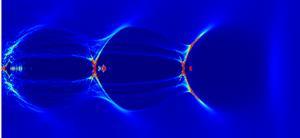

A computer simulation of the plasma wakefield as it evolves over the length of the 9-cm long channel. Credit: Berkeley Lab

At such high energies, the researchers needed to see how various parameters would affect the outcome. So they used computer simulations at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) to test the setup before ever turning on a laser. "Small changes in the setup give you big perturbations," says Eric Esarey, senior science advisor for the Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division at Berkeley Lab, who leads the theory effort. "We're homing in on the regions of operation and the best ways to control the accelerator."

In order to accelerate electrons to even higher energies--Leemans' near-term goal is 10 giga-electron volts--the researchers will need to more precisely control the density of the plasma channel through which the laser light flows. In essence, the researchers need to create a tunnel for the light pulse that's just the right shape to handle more-energetic electrons. Leemans says future work will demonstrate a new technique for plasma-channel shaping.

Comments