People exercise quite a lot, society has access to diverse fresh fruits and vegetables and yet most economic, educational, and racial or ethnic groups have seen their obesity levels rise at similar rates since the mid-1980s, so there is no demographic correlation to obesity. Yet the social sciences draw maps to city parks and farmer's markets and claim more of those would keep people from getting fat, or tout that economic redistribution would lead to less fast food.

Cars, fast food, iPads, city living, even women in the work force - if it is something in culture, someone has implicated it.

A new analysis in CA: Cancer Journal for Clinicians by Roland Sturm of the RAND Corp. think tank in Santa Monica and University of Illinois kinesiology and community health professor Ruopeng An tackled the list of societal trends and found most of them to be "unambiguously false".

Geography and the existence of so-called "food deserts" (neighborhoods or regions with limited access to affordable, healthy food) appear to have little bearing on the obesity trend in general, although they may be linked to differences between groups at any given point in time, An said.

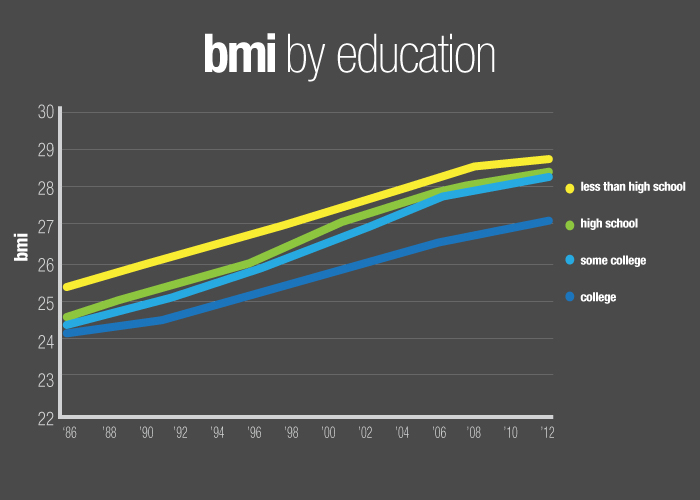

Obesity is going up at a similar rate in all groups. Credit: Julie McMahon

"A common misbelief is that the obesity epidemic reflects increasing social disparities and that the largest weight gains are concentrated in groups identifiable by race, ethnicity, income, education or geography," he said. "And it's true that if you look at the national data for any one point in time, it's not hard to figure out, for example, that the people with the lowest education tend to have the highest obesity rate. Everyone buys this argument. But what is less obvious is how surprisingly similar the obesity trend is for all groups."

A look at graphs of obesity over time (see The Obesity Trend) offers a more universal view of what is going on, An said. Obesity is higher for blacks than for whites, but both groups are getting heavier at almost the same rate over time. The same disparity is seen in people who never finished high school versus those with a college degree, or those with lower versus higher incomes. The trend lines vary somewhat – the gap between white men and black men has recently narrowed, for example, while the gap for black and white women has widened – but obesity is going up in all these groups at about the same rate, An said.

"The gap between groups is secondary to the increase that all groups experience over time," he said. "So a reversal of the obesity epidemic would need universal intuitions rather than a focus on certain groups."

Some common explanations for the upward surge in obesity are simply wrong, An said. For example, the idea that longer workdays or less leisure time are to blame is not supported by the data. Americans are working fewer hours and have more leisure time than they did in the 1960s, he said. People are spending less time on household chores and caring for dependents than they did decades ago, and they have more free time than ever, he said.

The notion that people are getting fatter because they have less access to affordable, healthy foods also contradicts the data, An said.

"The percent of disposable income spent on food fell quite a bit from 1970 to 2010," he said. "And in fact in the 1930s American people spent one-third of their disposable income on food, while today people spend less than one-tenth. So it's hard to argue that food has become more expensive in general."

The cost of fruits and vegetables has not increased over time, as some have argued, but has gone down more than 20 percent since 1970, the researchers report.

"The price of fruits and vegetables is decreasing – but not as rapidly as the cost of junk food," An said.

Overall, food is more accessible and affordable than ever in the United States, and this may be an important factor in the dramatic rise in obesity, he said.

The data on exercise and physical activity also are muddier than some people like to admit, An said. American participants in the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey reported in 2012 that they were exercising on average four minutes more a day than reported in 2003. But they also reported sleeping 10 minutes longer and watching 15 more minutes of TV.

"Self-reported exercise increases over time, and the total sedentary time also increases over time," An said. "So we are kind of in a dilemma trying to figure out what really contributes to the obesity epidemic. We have a lot of hypotheses but we really don't have much data to support them at this stage."

Comments