Scientists at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, and colleagues have discovered that a single monoclonal antibody--a protein that attacks viruses--isolated from a human Ebola virus disease survivor protected non-human primates when given as late as five days after lethal Ebola infection. The antibody can now advance to testing in humans as a potential treatment for Ebola virus disease. There are currently no licensed treatments for Ebola infection, which caused more than 11,000 deaths in the 2014-2015 outbreak in West Africa. The findings are described in two articles to be published online by Science on February 25.

NIAID researchers obtained and tested blood samples from a survivor of the 1995 Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and discovered the survivor retained antibodies against Ebola. Investigators from the Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Switzerland then isolated specific antibodies for potential use as a therapeutic for Ebola infection. Investigators from the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases administered a lethal dose of Zaire ebolavirus to four rhesus macaques, waited five days, and then treated three of the macaques with daily intravenous injections of the monoclonal antibody, known as mAb114, for three consecutive days. The untreated control macaque showed indicators of Ebola virus disease and died on day nine, but the treatment group survived and remained free of Ebola symptoms.

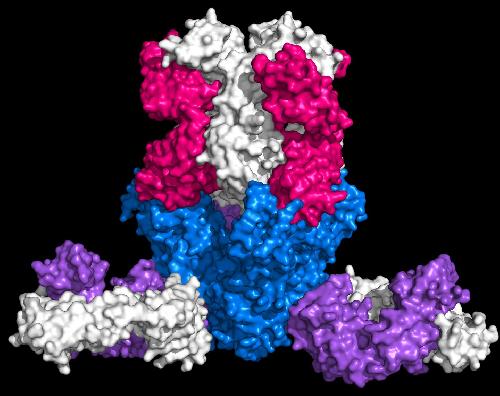

NIAID and Dartmouth College researchers then studied how mAb114 neutralizes the Ebola virus and determined that it binds to the core of the Ebola glycoprotein, blocking its interaction with a receptor on human cells. This area of the Ebola glycoprotein, called the receptor binding domain, was previously thought to be unreachable by antibodies because it is well-hidden by other parts of the virus, and only becomes exposed after the virus enters the inside of cells. This is the first antibody to demonstrate the ability to neutralize the virus by this interaction between the virus and its cellular receptor. Together the evidence identifies a novel site of vulnerability on the Ebola virus and suggests mAb114 could be an effective therapy and warrants further exploration, according to the authors.

Comments