Uranus is generally boring but it recently got interesting. It has become so stormy, with enormous cloud systems so bright, that for the first time ever amateur astronomers are able to see details in the planet's hazy blue-green atmosphere.

Astronomers detected eight large storms on Uranus's northern hemisphere while observing the planet with the Keck Telescope on August 5th and 6th. One was the brightest storm ever seen on Uranus at 2.2 microns, a wavelength that senses clouds just below the tropopause, where the pressure ranges from about 300 to 500 mbar, or half the pressure at Earth's surface.

The storm accounted for 30 percent of all light reflected by the rest of the planet at this wavelength. Citizen scientists also turned their telescopes on the planet to see examine the bright blotch on the surface.

Infrared images of Uranus (1.6 and 2.2 microns) obtained on Aug. 6, 2014, with adaptive optics on the 10-meter Keck telescope. The white spot is an extremely large storm that was brighter than any feature ever recorded on the planet in the 2.2 micron band. The cloud rotating into view at the lower-right limb grew into the large storm that was seen by amateur astronomers at visible wavelengths. Credit: Imke de Pater (UC Berkeley)&Keck Observatory images.

"The weather on Uranus is incredibly active," said Imke de Pater, professor and chair of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, and leader of the team that first noticed the activity when observing the planet with adaptive optics on the W. M. Keck II Telescope in Hawaii.

"This type of activity would have been expected in 2007, when Uranus's once every 42-year equinox occurred and the sun shined directly on the equator," noted co-investigator Heidi Hammel of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. "But we predicted that such activity would have died down by now. Why we see these incredible storms now is beyond anybody's guess."

'I got it!'

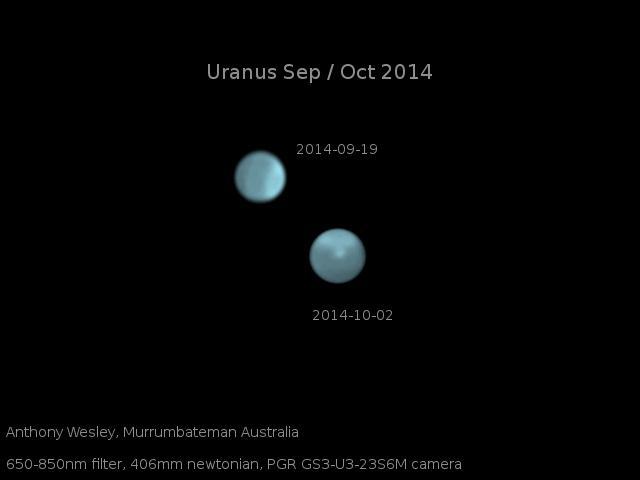

French amateur astronomer Marc Delcroix processed the amateur images and confirmed the discovery of a bright spot on an image by French amateur Régis De-Bénedictis, then in others taken by fellow amateurs in September and October. He had his own chance on Oct. 3 and 4 to photograph it with the Pic du Midi one-meter telescope, where on the second night, "I caught the feature when it was transiting, and I thought, 'Yes, I got it!'" said Delcroix.

"I was thrilled to see such activity on Uranus. Getting details on Mars, Jupiter or Saturn is now routine, but seeing details on Uranus and Neptune are the new frontiers for us amateurs and I did not want to miss that," said Delcroix, who works for an auto parts supplier in Toulouse and has been observing the skies - Jupiter in particular - with his backyard telescope since 2006 and, since 2012, occasionally with the Pic du Midi telescope. "I was so happy to confirm myself these first amateur images on this bright storm on Uranus, feeling I was living a very special moment for planetary amateur astronomy."

The extremely bright storm seen by Keck in the near infrared is not the one seen by the amateurs, which is much deeper in the atmosphere than the one that initially caused all the excitement. De Pater's colleague Larry Sromovsky, a planetary scientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, identified the amateur spot as one of the few features on the Keck images from August 5 that was only seen at 1.6 microns, and not at 2.2 microns.

The 1.6 micron light is emitted from deeper in the atmosphere, which means that this feature is below the uppermost cloud layer of methane-ice in Uranus's atmosphere.

"The colors and morphology of this cloud complex suggests that the storm may be tied to a vortex in the deeper atmosphere similar to two large cloud complexes seen during the equinox," Sromovsky said.

Such vortices could be anchored much deeper in the atmosphere and extend over large vertical distances, as inferred from similar vortices on Jupiter, including its Great Red Spot.

An expanded team of astronomers led by Kunio M. Sayanagi, an Assistant Professor at Hampton University in Virginia, leveraged the amateur observations to activate a "Target of Opportunity" proposal on the Hubble Space Telescope, which imaged the entire planet on Oct. 14. Observing at a variety of wavelengths, HST revealed multiple storm components extending over a distance of more than 9,000 kilometers (5,760 miles) and clouds at a variety of altitudes.

These are optical images of Uranus on Sept. 19 and Oct. 2, showing the dramatic appearance of a bright storm on a planet that normally displays only a diffuse bright polar region. Photo by Anthony Wesley, Murrumbateman, Australia.

Ice giant

Uranus is an ice giant, about four times the diameter of Earth, with an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium, with just a bit of methane to give it a blue tint. Because it is so distant - 30 times farther from the sun than Earth - astronomers were able to see little detail on its surface until adaptive optics on the Keck telescopes revealed features much like those on Jupiter.

De Pater and her colleagues have been following Uranus for more than a decade, charting the weather on the planet, including bands of circulating clouds, massive swirling storms and convective features at its north pole. Bright clouds are probably caused by gases such as methane rising in the atmosphere and condensing into highly reflective clouds of methane ice.

Because Uranus has no internal source of heat, its atmospheric activity was thought to be driven solely by sunlight, which is now weak in the northern hemisphere. Hence astronomers were surprised when these observations showed such intense activity.

Observations taken with the Keck telescope by Christoph Baranec, an Assistant Professor at the University of Hawaii on Manoa, revealed that the storm was still active, but had a different morphology and possibly reduced intensity.

"If indeed these features are high-altitude clouds generated by flow perturbations associated with a deeper vortex system, such drastic fluctuations in intensity would indeed be possible," Sromovsky added.

"These unexpected observations remind us keenly of how little we understand about atmospheric dynamics in outer planet atmospheres," the authors wrote in their paper.

Comments