You might recall that a few years ago, lots of athletes wore magnetic bracelets in the belief that their performance would improve. Like much woo, be it homeopathy or organic food or skull drilling, it proceeded from a reasonable basis; in the case of magnets, are we not governed by inductance? What if we could more optimally guide our bodily functions using mass-produced magnets? Then throw in a bunch of stuff about negative ions and tourmaline and get rich.

Today you can pick up those used for a dollar on Ebay.

But there is obviously science involved in magnetism and nanoparticles, even if it isn't to be found in a cheap copper bracelet. Using artificial white blood cells, artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPCs), designed to target cancer-fighting immune cells, Johns Hopkins researchers have trained the immune systems of mice to fight melanoma, a deadly skin cancer. The experiments represent a significant step toward using nanoparticles and magnetism to treat a variety of conditions, the researchers say.

To fight cancer, the aAPCs must interact with immune cells known as naive T cells that are already present in the body, awaiting instructions about which specific invader they will battle. The aAPCs bind to specialized receptors on the T cells' surfaces and "presenting" them with distinctive proteins called antigens. This process activates the T cells, programming them to battle a specific threat such as a virus, bacteria or tumor, as well as to make more T cells.

|

|

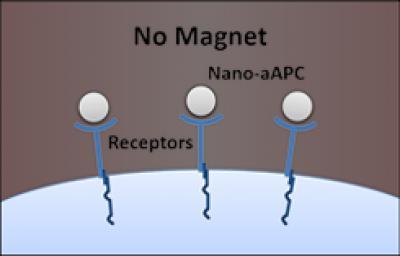

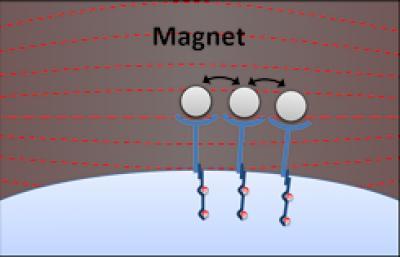

On the left, a nanoscale artificial antigen presenting cells (nano-aAPCs) bound to receptors on the T cell surface. On the right, applying a magnetic field caused the nano-aAPCs, and their receptors, to cluster together, leading to T cell stimulation. Credit: Karlo Perica

The team had been working with microscale particles, which are about one-hundredth of a millimeter across. But, says Jonathan Schneck, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of pathology, medicine and oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's Institute for Cell Engineering, aAPCs of that size are still too large to get into some areas of a body and may even cause tissue damage because of their relatively large size.

In addition, the microscale particles bound equally well to naive T cells and others, so the team began to explore using much smaller nanoscale aAPCs. Since size and shape are central to how aAPCs interact with T cells, Karlo Perica, a graduate student in Schneck's laboratory, tested the impact of these smaller particles.

The so-called nano-aAPCs were small enough that many of them could bind to a single T cell, as the team had expected. But when Perica compared naive T cells to those that had been activated, he found that the naive cells were able to bind more nanoparticles. "This was quite surprising, since many studies had already shown that naive and activated T cells had equal numbers of receptors," Schneck says. "Based on Karlo's results, we suspected that the activated cells' receptors were configured in a way that limited the number of nanoparticles that could bind to them."

To see whether there indeed was a relationship between activation and receptor clustering, Perica applied a magnetic field to the cells, causing the nano-aAPCs to attract one another and cluster together, bringing the receptors with them. The clustering did indeed activate the naive T cells, and it made the activated cells even more active — effectively ramping up the normal immune response.

To examine how the increased activation would play out in living animals, the team treated a sample of T cells with nano-aAPCs targeting those T cells programmed to battle melanoma. The researchers next put the treated cells under a magnetic field and then put them into mice with skin tumors. The tumors in mice treated with both nano-aAPCs and magnetism stopped growing, and by the end of the experiment, they were about 10 times smaller than those of untreated mice, the researchers found. In addition, they report, six of the eight magnetism-treated mice survived for more than four weeks showing no signs of tumor growth, compared to zero of the untreated mice.

"We were able to fine-tune the strength of the immune response by varying the strength of the magnetic field and how long it was applied, much as different doses of a drug yield different effects," says Perica. "We think this is the first time magnetic fields have acted like medicine in this way."

In addition to its potential medical applications, Perica notes that combining nanoparticles and magnetism may give researchers a new window into fundamental biological processes. "In my field, immunology, a major puzzle is how T cells pick out the antigen they're targeting in a sea of similar antigens in order to find and destroy a specific threat," he says. "Receptors are key to that action, and the nano-aAPCs let us detect what the receptors are doing."

"We have a bevy of new questions to work on now: What's the optimal magnetic 'dose'? Could we use magnetic fields to activate T cells without taking them out of the body? And could magnets be used to target an immune response to a particular part of the body, such as a tumor's location?" Schneck adds. "We're excited to see where this new avenue of research takes us."

Comments