You may not know it but on our biosphere - Earth - there is also a relatively unknown world hiding in plain sight. It is composed of microbes that live on floating pieces of plastic floating on the ocean.

This "Plastisphere" of microbial organisms living on ocean plastic that was first discovered last year and it is now getting studied.

When researchers first examined the Plastisphere, they found at least 1,000 different types of microbes living on the tiny plastic islands, and worried that they might pose a risk to larger animals, including invertebrates and humans. They also found that the Plastisphere's inhabitants included bacteria known to cause diseases in animals and humans. Since then, researchers have been trying to figure out why these potentially dangerous bacteria live on the Plastisphere, how they got there and how they are affecting the surrounding ocean.

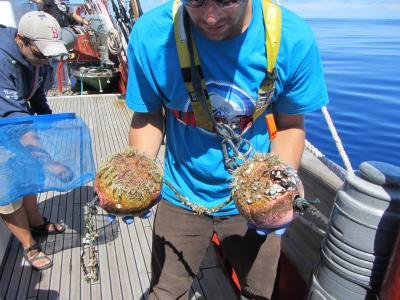

SEA Education Association scientist Greg Boyd holds recovered foam floats containing invertebrates and microbial biofilm. New research being presented at the Ocean Sciences Meeting delves deeper into the role microbial communities living on plastic marine debris play in the ocean ecosystem. Credit: Erik Zettler, SEA

New evidence suggests that "super-colonizers" form detectable clusters on the plastic in minutes. Other findings indicate that some types of harmful bacteria favor plastics more than others. And, scientists are exploring if fish or other ocean animals may be helping these pathogens thrive by ingesting the plastic. That could allow bacteria to acquire additional nutrients as they pass through the guts of the fish, said Tracy Mincer, an associate scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Mass.

Revealing this information could help scientists better understand how much of a potential threat these harmful bacteria pose and the role the Plastisphere plays in the larger ocean ecosystem, including its potential to alter nutrients in the water. That information could also help reduce the impact of plastic pollution in the ocean – for instance, if plastics manufacturers learned how to make their products so they degrade at an optimal rate, Mincer said.

"One of the benefits of understanding the Plastisphere right now and how it interacts with biota in general, is that we are better able to inform materials scientists on how to make better materials and, if they do get out to sea, have the lowest impact possible," said Mincer, who discovered the Plastisphere last year along with Linda Amaral-Zettler at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) and Erik Zettler at the SEA Education Association, both also in Woods Hole.

Other new results include discoveries about how the plastic is colonized and how it interacts with other marine organisms. Yet additional findings shed light on the similarities and differences between Plastisphere communities in different locations and on different types of plastic. This research could help scientists determine the age of plastic floating in the ocean, which could help them figure out how it breaks down in the water. It could also potentially aid in determining where the plastic debris came from, and how the plastic and the microbes that live on board could impact organisms that come into contact with them, the scientists said.

"It is clear," said Amaral-Zettler, "that the Plastisphere definitely has a function out there in the ocean" and these experiments seek to quantify what it is.

Comments