Despite a malfunction that ended its primary mission in May 2013, the Kepler spacecraft is still alive and working and its data has found a new "super-Earth".

NASA's Kepler spacecraft detected planets by looking for transits, when a star dims slightly as a planet crosses in front of it. The smaller the planet, the weaker the dimming, so brightness measurements must be precise and that requires maintaining a steady pointing. Kepler can't really do that any more, its primary functionality came to an end when the second of four reaction wheels used to stabilize the spacecraft failed. Without at least three functioning reaction wheels, Kepler couldn't be pointed accurately.

To compensate, engineers developed a strategy to use pressure from sunlight as a virtual reaction wheel to help control the spacecraft and achieve about half the photometric precision of Kepler when it was still fully functional. They believe they can not only continue Kepler's search for other worlds, but also introduce new opportunities to observe star clusters, active galaxies, and supernovae.

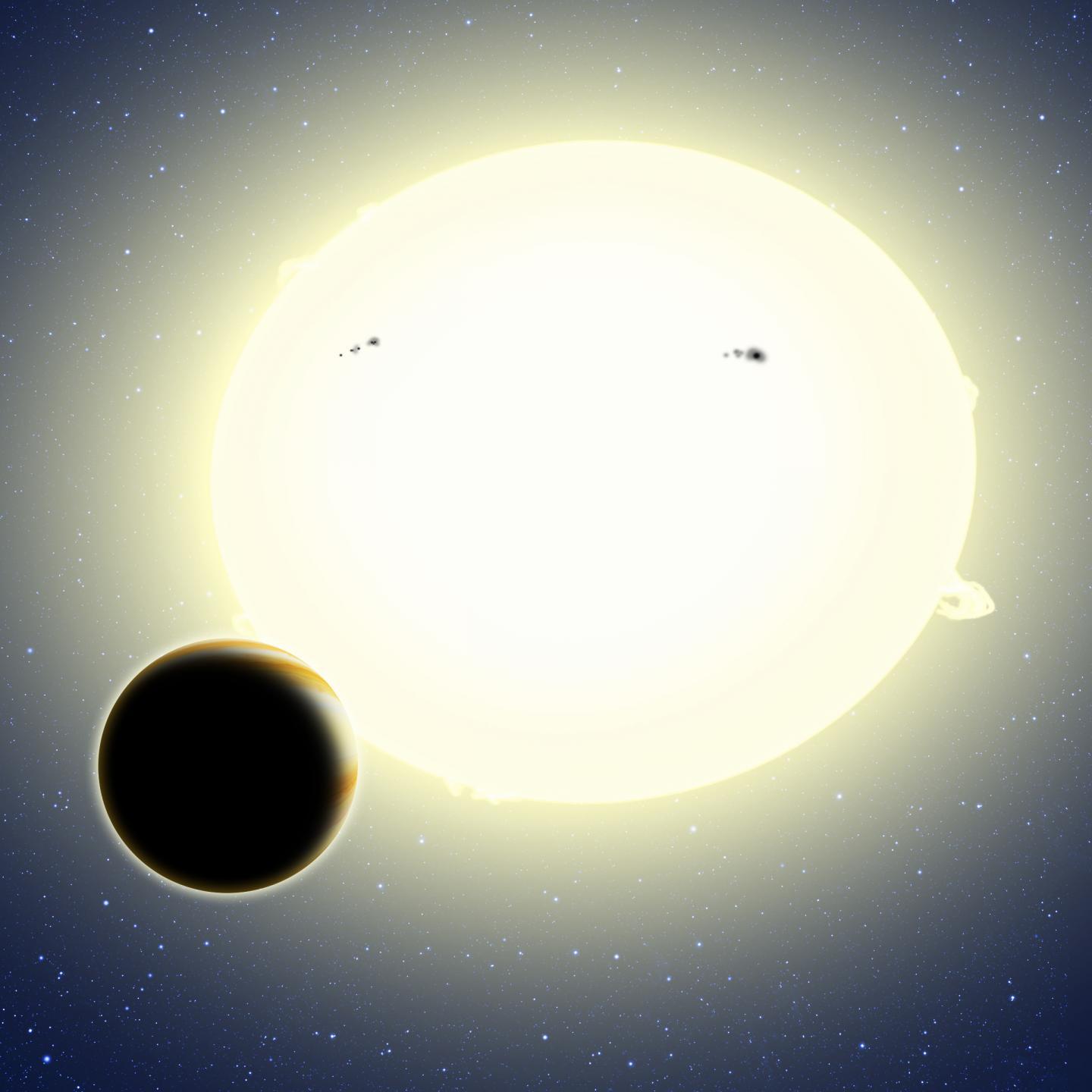

Artist's conception of HIP 116454b, with a diameter of 20,000 miles (two and a half times the size of Earth) and weighing 12 times as much. It orbits its star once every 9.1 days. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA)

Due to Kepler's reduced pointing capabilities, extracting useful data requires better computer analysis. Andrew Vanderburg of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and colleagues developed specialized software to correct for spacecraft movements. Kepler's new life began with a 9-day test in February 2014. When Vanderburg and his colleagues analyzed that data, they found that Kepler had detected a single planetary transit.

They confirmed the discovery with radial velocity measurements from the HARPS-North spectrograph on the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands. Additional transits were weakly detected by the Microvariability and Oscillations of STars (MOST) satellite.

The newfound planet, HIP 116454b, has a diameter of 20,000 miles, two and a half times the size of Earth. HARPS-N showed that it weighs almost 12 times as much as Earth. This makes HIP 116454b a super-Earth, a class of planets that doesn't exist in our solar system. The average density suggests that this planet is either a water world (composed of about three-fourths water and one-fourth rock) or a mini-Neptune with an extended, gaseous atmosphere.

This close-in planet circles its star once every 9.1 days at a distance of 8.4 million miles. Its host star is a type K orange dwarf slightly smaller and cooler than our sun. The system is 180 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pisces.

Since the host star is relatively bright and nearby, follow-up studies will be easier to conduct than for many Kepler planets orbiting fainter, more distant stars.

"HIP 116454b will be a top target for telescopes on the ground and in space," says Harvard astronomer and co-author John Johnson of the CfA.

Comments