There is a bad habit in environmental circles, created by the academics that feed them information: Discovering a new species and immediately declaring it endangered. More evidence-based scientists recognize that over 99.99999% of all species that have gone extinct we never knew about in the first place so declaring everything endangered and claiming a domino effect undermines public acceptance of science. Nonetheless, a new paper adds to the former effort by saying we should forget species extinction and talk about species rarity.

Yale's Pincelli Hull and colleagues from the Smithsonian Institution argue that modern extinction rates may be a poor measure of whether we're in the midst of a mass extinction event today -- something many scientists suspect may be happening. Instead, Hull and her co-authors contend, the best way to see a mass extinction in real time is by studying changes in species and ecosystems.

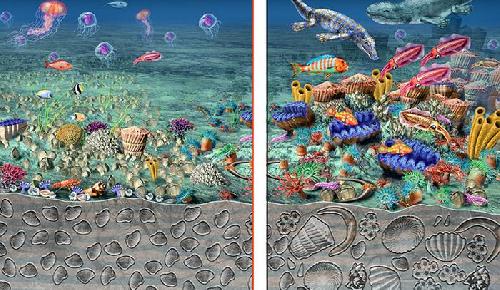

Earth has experienced more than a dozen mass extinction events, when the great diversity of life on Earth disappeared and was replaced by a flora or fauna often entirely unlike what had come before. The largest of these events (the most recent, which wiped out the dinosaurs, was 66 million years ago) have collectively become known as the "Five Mass Extinctions." A new sixth mass extinction was the topic of Elizabeth Kolbert's Pulitzer Prize-winning advocacy book, "The Sixth Extinction."

Hull and co-authors Simon Darroch and Douglas Erwin contend that long before species become extinct, their rarity may cause far-reaching changes in global ecosystems. In fact, the researchers explain, the rarity of previously abundant species and ecosystems alone may be enough to drive permanent shifts in the biosphere. A review of the fossil record, they said, shows that rarity of previously abundant organisms is the only factor tied with certainty to the widespread ecological change observed across extinction boundaries, and because of this, the magnitude and extent of rarity may provide the best comparison of the current biotic crisis to those of the past.

"Ecology tells us that ecosystems can collapse completely on timescales ranging from 100 to 10,000 years, which is a process that typically isn't preserved in the fossil record, so we simply don't have a good idea of what these transitional ecosystems look like," Darroch said. "Figuring out how mass rarity in a wide range of species in today's oceans may scale up to a mass extinction on longer timescales is one of the great scientific challenges of our generation."

The researchers note, for example, that the modern ocean is full of ecological "ghosts" -- species that are now so rare that they no longer fill the ecological roles they did previously, when they were more abundant. In other words, species rarity itself, rather than extinction, can lead to a cascade of changes within ecosystems, long before the species goes extinct, the scientists explain.

Published in Nature.

Comments