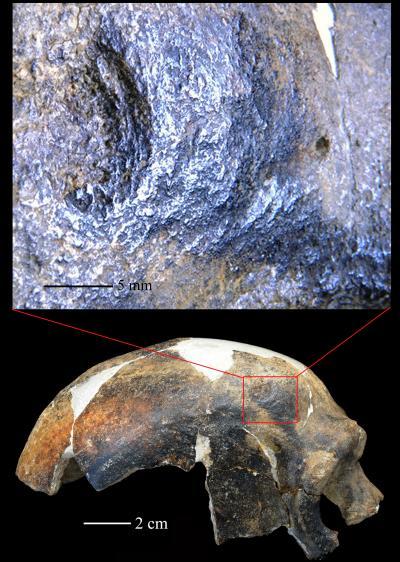

A report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that a 14 mm ridged, healed lesion with bone depressed inward to the brain resulted from localized blunt force trauma. Was it an accident or interhuman aggression?

The Maba cranium was discovered with the remains of other mammals in June 1958, in a cave at Lion Rock in Guangdong province, China. The Maba cranium and associated animal bones were unearthed at a depth of one meter by farmers removing cave sediments for fertilizer.

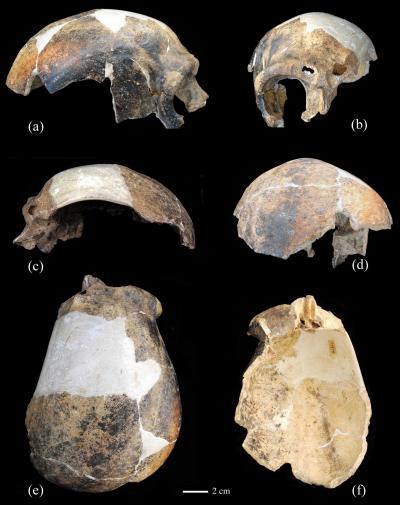

Reconstructed Maba 1 cranium (A) Right lateral view (B) anterior view (C) left lateral view (D) posterior view (E) superior view (F) basal view. Credit: University of the Witwatersrand

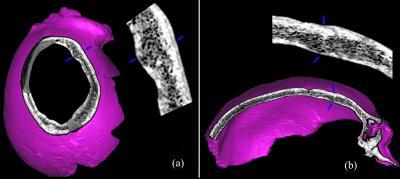

The Maba cranium is housed in the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and was analyzed visually using stereomicroscopy and a high-resolution industrial CT scanner. This state-of-the-art imaging technology enabled the researchers to investigate the inner structure of the bone to verify that healing had occurred.

CT reconstructions depicting the lesion on the Maba cranium. Credit: University of the Witwatersrand

"This wound is very similar to what is observed today when someone is struck forcibly with a heavy blunt object. As such it joins a small sample of Ice Age humans with probable evidence of humanly induced trauma, and could possibly be the oldest example of interhuman aggression and human induced trauma documented. Its remodeled, healed condition also indicates the survival of a serious brain injury, a circumstance that is increasingly documented for archaic and modern Homo through the Pleistocene," comments Prof. Lynne Schepartz from the School of Anatomical Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, one of the co-authors of the paper.

Right superolateral view of the Maba cranium showing the position (A) and detail (B) of the depressed lesion. Credit: University of the Witwatersrand

"It is not possible to assess whether the incident was accidental or intentional, or whether it resulted from a short-term disagreement, or premeditated aggression."

Why is this study important?

"The identification of traumatic lesions in human fossils is of interest for assessing the relative risk of injury to different human groups, the location of trauma, and the behavioral implications," adds Schepartz. "It also helps us to identify and understand some the earliest forms of interhuman aggression, and the abilities of Pleistocene humans to survive serious injury and post-traumatic disabilities. Maba would have needed social support and help in terms of care and feeding to recover from this wound."

Comments