Wind energy is getting a lot of attention and a lot of money - it just isn't generating a lot of electricity yet, no matter what gets claimed in rosy projections. In the real world, they do quite poorly and building more of them doesn't fix it. Dr. Hui Hu and his group at Iowa State University want to solve a puzzle that has stumped scientists and engineers for hundreds of years; how to make wind work.

Using a large-scale Aerodynamics/Atmospheric Boundary Layer (AABL) Wind Tunnel at Iowa State University, they studied the effects of the relative rotation directions of two tandem wind turbines on the power production performance, the flow characteristics in the turbine wake flows, and the resultant wind loads acting on the turbines.

In a typical wind farm, the wind turbine located in the wakes of upstream turbines would experience a significantly different surface wind compared to the ones located upwind due to the wake interferences of the upwind turbines. Depending on the wind turbine array spacing and layout, the power losses of downstream turbines due to the wake interferences were found to be up to 40%.

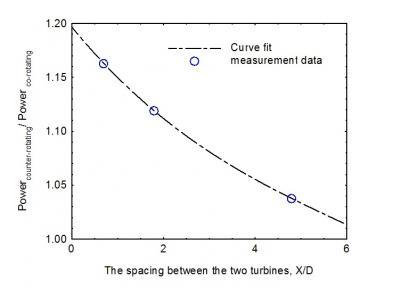

The ratios of power outputs for the downstream turbine in counter-rotating to those in co-rotating as a function of the spacing between the turbines. Credit: Science China Press

How to improve the power production of downstream wind turbines in a wind farm is one of the most significant research topics in recent years. Extensive experimental and numerical studies have been conducted recently to examine wind turbine aeromechanics and wake interferences among multiple wind turbines in order to gain insight into the underlying physics for higher total power yield and better durability of the wind turbines.

While most of the wind turbines in modern wind farms are Single Rotor Wind Turbine (SRWT) systems, the concept of Counter-Rotating Wind Turbine (CRWT) systems has been suggested in recent years. Since azimuthal velocity would be induced in the wake flow behind a wind turbine with its rotation direction in the opposite direction to the upstream rotor, the downstream rotor should rotate in the same direction as the swirling wake flow for a CRWT system in order to extract wind energy in the wake flow more efficiently.

So far, since the distance between the two rotors in a CRWT system is always very small (i.e., less than 1D, and D is the rotor diameters), the attempts of CRWT to improve wind energy utilization are focused on near wake characteristics. On the other hand, most of the previous studies on the wake interferences among multiple turbines are limited to SRWT systems with all the turbines rotating in the same direction. The wake interferences among SRWT systems with different rotation directions in a wind farm have never been investigated before.

With this in mind, Hu and his group conducted a comprehensive experimental study to quantify the effects of the relative rotation direction of two tandem wind turbines on the wake interferences among the turbines. While the oncoming flow was kept constant during the experiments, the model turbines were set to operate in either co-rotating (i.e., the downstream turbine has the same rotation direction as the upstream turbine) or counter-rotating (i.e., the downstream turbine has an opposite rotation direction in relation to the upstream turbine) configuration.

The turbine power outputs, the static and dynamic wind loads (i.e., aerodynamic forces and bending moments) acting on the turbines, and the turbulence characteristics in the wake flows behind the turbines were measured and compared quantitatively.

It was found that the turbines in counter-rotating would harvest more wind energy from the same oncoming wind, compared with the co-rotating case. While the recovery of the streamwise velocity deficits in the wake flows was found to be almost identical with the turbines operated in either co-rotating or counter-rotating, the significant azimuthal velocity generated in the wake flow behind the upstream turbine is believed to be the reason why the counter-rotating turbines would have a better power production performance.

Since the azimuthal velocity in the wake flow was found to decrease monotonically with the increasing downstream distance, the benefit of the counter-rotating configuration was found to decrease gradually as the spacing between the turbines increases. While the counter-rotating downstream turbine was found to be able to produce up to 20% more power compared with the co-rotating downstream turbine when the spacing between the turbines was 0.7 rotor diameters (i.e., 0.7D), the advantage of the counter-rotating configuration was found to be reduced to only about 4.0% when the spacing between the turbines was increased to about 5.0D.

Since the azimuthal flow velocity in the wake flow was found to become almost negligible in the further downstream region, the benefits of the counter-rotating configuration were found to die away (i.e., <1.0%) when the spacing between the turbines becomes greater than 6.5D.

It suggests that, on the practical relevance of wind farm design, counter-rotating configuration would be more beneficial to onshore wind farms, compared with offshore wind farms, due to the much smaller spacing between the turbines (i.e., ~3 rotor diameters for onshore wind farms vs. 6~10 rotor diameters for offshore wind farms), especially for those turbines sited over the mountains/hills with the spacing between the turbines only about 1~2 rotor diameters.

Comments