Researchers have shown that an enzyme key to regulating gene expression -- and also an oncogene when mutated -- is critical for the expression of numerous inflammatory compounds that have been implicated in age-related increases in cancer and tissue degeneration,

Inhibitors of the enzyme are being developed as a new anti-cancer target.

Aged and damaged cells frequently undergo a form of proliferation arrest called cellular senescence. These fading cells increase in human tissues with aging and are thought to contribute to age-related increases in both cancer and inflammation. The secretion of such inflammatory compounds as cytokines, growth factors, and proteases is called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, or SASP.

In a study published this week in Genes&Development, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of the enzyme, called MLL1, in both human cells and mice prevents the deleterious activation of the DNA damage response, which causes SASP expression.

"Since tumor-promoting inflammation is one of the hallmarks of cancer, these findings suggest that MLL1 inhibitors may be highly potent anti-cancer drugs through both direct epigenetic effects on proliferation-promoting genes, as well as through the inhibition of inflammation in the tumor microenvironment," says first author Brian Capell, MD, PhD, a medical fellow in the lab of Shelley Berger, PhD of the University of Pennsylvania.

The mechanism of this inhibition is through the direct epigenetic regulation by MLL1 of critical proliferation-promoting cell cycle genes that are required for triggering the DNA damage response in the body. MLL1 is an enzyme that adds methyl groups to loosen chromatin, the proteins around which DNA winds, so that part of the genome can be "read" and translated into proteins - its epigenetic role. However, MLL1 is also commonly mutated in numerous human cancers, particularly in pediatric and adult blood cancers.

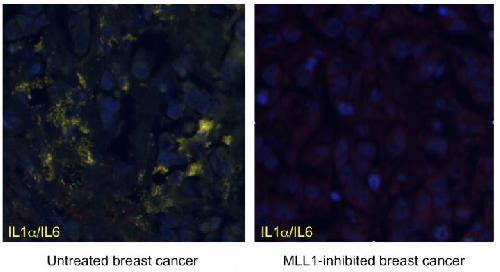

"We show that MLL1 inhibition blocks the expression of inflammatory genes in both senescent and cancerous human cells, including those derived from human breast cancer" Capell said.

Knowing that MLL1 has been implicated in cell-cycle regulation, when the researchers inhibited MLL1, proliferation-promoting genes were shut down and the DNA damage response and resulting inflammation was suppressed. Indeed, in the case of applying this result to fighting cancer, this is a desired effect, since an increase in inflammation can promote both the development and progression of cancer.

"In cancer, this could be a potent one-two punch, by blocking both proliferation-promoting genes as well as the cancerous inflammation," Capell explained. "One could imagine taking an MLL1 inhibitor as a primary treatment, but also as an adjuvant therapy to tamp down the rampant inflammation caused by drugs like chemotherapies. More speculatively, given that the SASP has been implicated in numerous other age-related disorders, it will be worth testing the effects of MLL1 inhibition in other aging and inflammatory disease models."

Comments